PUJA SPECIAL

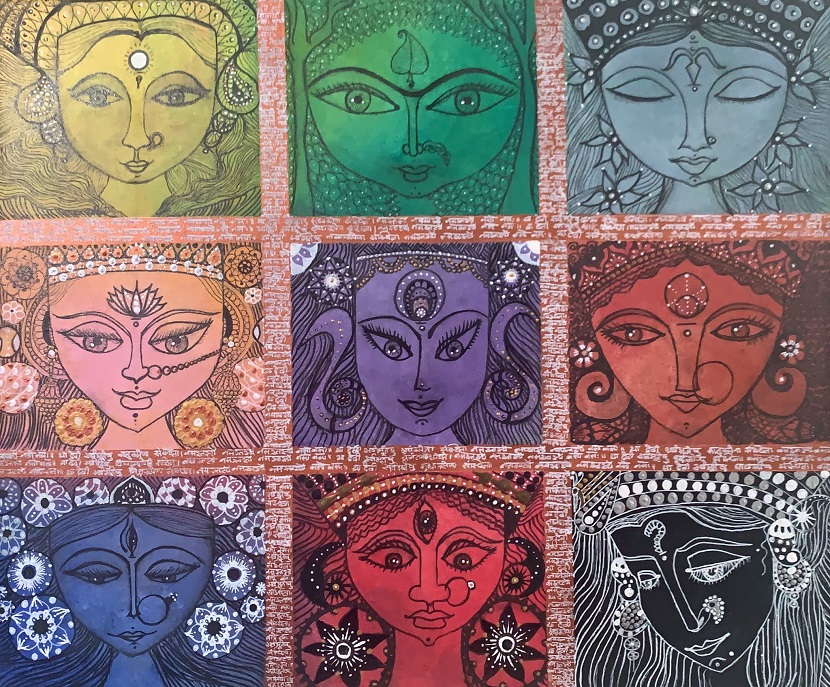

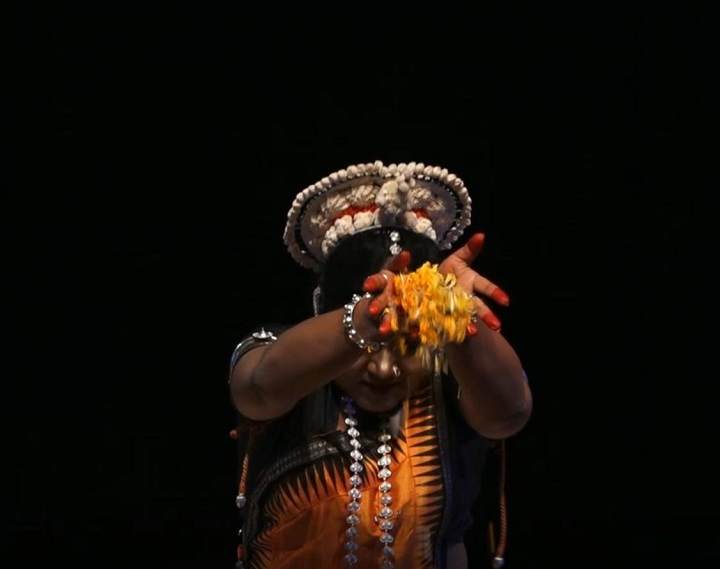

Title of the Painting: EXPRESSIONS OF DEVI

Each day of Navratri is dedicated to the various avatars of Goddess Durga with different colors and expressions. Yellow symbolizes that omnipotent Devi abiding in the form of Memory, green - in the Source of Life, grey - in a form of Peace, orange - in the form of Motherhood, white - in the form of Modesty, red - in the form of Power, blue - in the form of Forbearance, pink - in the form of Prosperity and purple - in the form of Wisdom.

Each form she takes over the 9 days is showcased and mirrors the roopams in the shloka Devi Suktam.

Ms Neeraja Sundar Rajan is a healthcare professional with a Masters in Chemical Engineering. She is multifaceted with a passion for art and Carnatic Music. She is an animal lover and cares deeply about their welfare.

Dear Friends,

I have great pleasure in offering you a Special Edition of LiteraryVibes on the occasion of the holy festival of Dussehra. Hope the brilliant and entertaining stories contained in this Puja Special will fill your holidays with abundant joy.

Please share the link https://positivevibes.today/article/newsview/457 with your friends and contacts in true festive spirit.

Your feedback and comments will undoubtedly bring a smile to the writers. Please use the Comments box at the bottom of the page for the same.

Let me wish you a Happy Dussehra. This is the beginning of the festive season, with Sharad Purnima, Deepavali, Christmas and New Year waiting around the corner. May you have lots of joy and tons of blessings in the coming days.

With warm regards

Mrutyunjay Sarangi

Table of Contents :: PUJA SPECIAL

01) Prabhanjan K. Mishra

WHO WAS KAKOLI?

02) Sreekumar K

MISS YOU

03) Ajay Upadhyaya

TO SPEAK OR NOT TO …

04) Ishwar Pati

THE EXQUISITE BLISS OF DUNKED BISCUITS

05) Chinmayee Barik

A CUP OF SUGAR

06) Krupasagar Sahoo

DIDI FROM DUM DUM

07) Prasanna Dash

ANADI SARDAR

08) Meena Mishra

WHO KNOWS THE TRUTH?

09) Jairam Seshadri

BOZO AND WIZO AT THE FANTASY ISLAND ZOO

10) Satya N. Mohanty

WHEN GOD WAS A BUSINESSMAN

11) Sundar Rajan S

THE CAR RIDE

12) Shruti Sarma

DEVI

13) Sulochana Ram Mohan

RECIPE FOR A FAMILY DRAMA

14) Punyasweta Mohanty

THE UNDEAD

15) Gita Bharath

LOCKDOWN TIMES

16) G K Maya

TRANCE

17) Archee Biswal

NATURE’S BEST FRIEND

18) Subha Bharadwaj

NAVARATHRI

19) Prof. (Dr) Viyatprajna Acharya

AS YOU WISH O MOTHER DIVINE!

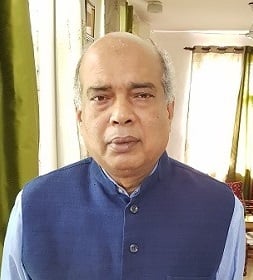

20) Mrutyunjay Sarangi

THE EMBER

WHO WAS KAKOLI?

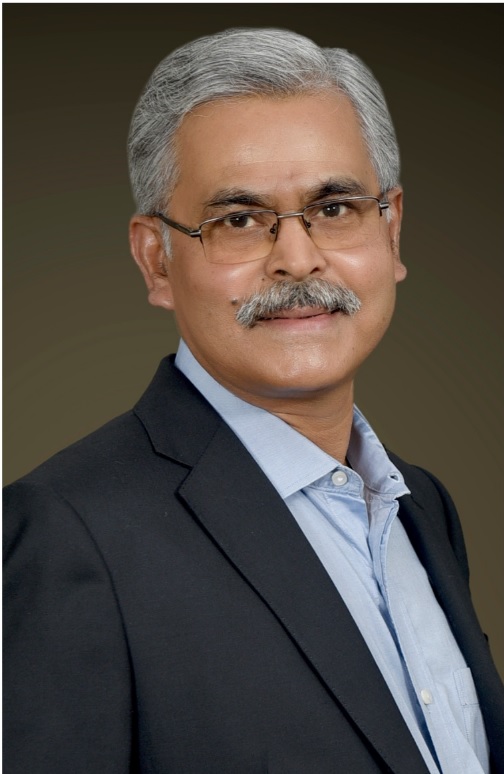

Prabhanjan K. Mishra

‘KAKOLI’, as a word, means ‘the sweet chirping of a song bird or chirruping of birds collectively’. For knowing Kakoli, as a person, a girl, or a woman, one is to listen to at least two personal reflections.

***

Anubhuti’s Story –

I came to Banaras to work as an IT engineer. Before that, I knew the city as the seat of Lord Kasi Vishwanath. I knew this old city also for its famous ghats on the holy Ganga where corpses were brought from far and near for cremation, as those holy ghats on the river Ganga were believed to be gateways to heaven.

My love for the city, however, was for a different reason. My mother was sent here by her in-laws’ family after she became a widow around thirteen years ago. She had to live here and was supposed to be conducting penance for her sins that had brought her the widowhood as a divine punishment upon her. She, in my understanding, had been a sinless woman all her life.

By my twenty-second birthday, I had an IT Engineering degree and a campus selection in my portfolio by an IT company. I had made a specific request at the time, if selected, my posting might be considered for the IT compay’s branch in the city of Banaras. My attraction was to stay in the same city where my mother had been living.

After I came to the holy city, I found my mother living like a shadow of herself in a widow shelter home under the management of a monk who ran a monastery also. I learnt from my mother the painful journey of her life moving from the small town, Naihati, in Bengal on the bank of the holy Ganga to an alien coastal village in Odisha after getting married there, and then moving finally to Banaras as a widow for doing penance.

She showed me the secret postcard size photograph of her heartthrob, and to my surprise, the man in the photograph was not my father. The fellow in the photograph looked like any of my handsome college day male friends. He had a lean face with a suspicion of soft facial sprouts on the chin and a shock of bushy black hair on his head. He was smiling in a vague way. But he had remarkable shining eyes.

The same photograph, I recalled, she had shown me at the time of her departure from my paternal village in Odisha for Banaras as a young widow. I had been a girl of nine at the time, and hardly understood the significance of what she had babbled to me about it.

I would recall from my childhood, she had been a constant babbler in my father’s house, but because of the low volume it was difficult to understand what she was saying. All her in-laws disliked her, but my father loved her. He was much older to her. He would call her affectionately ‘Meri Pagli’, meaning ‘my mad woman’.

At Banaras, she told me all about that boy in the photograph claiming that he had been her heartthrob all along from her unmarried years, and she loved him to that day.

She whispered to me one day that I was the fruit of that nubile love between her and the boy in that photograph. I was dumbstruck to know that my father Dhanwantari Das was not my biological father, but instead, it was one Subbu alias Subrat Mukherji. She also told me about her tragic life-story, the turn of events that had suddenly whisked her away to Odisha from her Bengal home to marry an aged stranger in an alien land. She cried like a child in my lap for her Subbu.

She had whispered pointing to the young fellow in the photograph, “This is your papa, your real papa. Danwantari only married my body, but my soul was already married to Subbu. You know, you came inside me in a dark wet bathroom that was illuminated only by the heavenly chandeliers of our love, Subbu’s and mine. In that happiest hour we were on a slippery wet floor like a pair of mermaid and merman.”

She would add with a smile, “In fact, your father, Subbu, on entering the bathroom, had the first impression that I was a mermaid that had escaped from the nearby Ganga and had taken shelter in our bathroom.”

To my question, “Why didn’t you marry Subbu?” She would shrug her shoulders, “He went away to Bombay after his holiday to join college. I bore his memory in my loving womb. Then your grandma died and my uncles sold me forcibly to an agent. I sent a letter to Subbu but no reply came. I was married off that very month. Dhanwantari my husband never guessed I was pregnant. He accepted you as his child.”

She would lower her voice further, “Subbu had kept a name for me that he used in our private meetings.” To my inquiry about that name, she would shy away, “Ish..ishish.., don’t ask. I won’t tell you. I am bound by my oath to Subbu not to tell it to anyone.”

Then turning serious, “If you ever find your father, don’t forget to tell him that his wife and soul-mate ‘Mouli’ had transformed the dream into reality, the dream seen together. I have named his daughter as agreed between us. Also, tell him that his child-wife Mouli treasured his memory to her last breath and remained loyal to him.” I thought my mother and her Subbu might have pre-agreed to name me ‘Anubhuti’.”

She would often walk her memory lanes, “The people of Odisha are heartless, otherwise, why should Dhanwantari Das buy me, a girl from Bengal, to marry when he had two wives already? And when I became a widow for none of my fault, why should my in-laws send me to Banaras to live in a widow home, beg for my food and do penance for sins that I never committed?”

Then her voice would turn angry, “In fact, my greedy in-laws were afraid, I might ask for a slice of the late Danwantari’s vast property as his third widow. How did his two senior widows live there as sinless women? It was because they were from the local Odia stock with maternal family living in nearby villages and would not tolerate injustice to them. But I was a poor Bengali orphan bought by Dhanwantari to marry from a marriage-broker. Ha!”

I learnt that like all other widows driven out of homes and gathering at holy cities like Banaras, my mother lived in the dormitory of a widow home, paying for her stay and food from her alms that she collected from begging at different temples.

I learnt from my mother the misery of widows that chased them their whole lives, at their own houses after the husband’s death, then at the holy places where they were sent. They were sometimes victims of sex-rackets at the hands of fake-holy men, at times willingly in exchange of a little better amenities of life, but mostly forced into it. Their female body was their enemy.

I decided, along with a few of my like-minded friends, to start an NGO for alleviating the condition of widows. We started planning, collecting from crowd funding, and saving funds for it. I thought that would be the best gift from me to my mother.

I had to pay a little to the monastery authority to free my mother from her from them. She came to live with me in my rented two-room accommodation. By then, she was suffering from an ulcerated stomach developed and worsened by prolonged starvation and anxiety. She would at times mumble about her grandma’s generous ways, and eating with her the crispy kachoris with succulent rasgullas at her grandma’s house.

She would whisper, “You look like my split image, my child, in every respect except my eyes. Your eyes are pretty like your father’s, not ordinary like mine.” I couldn’t find anything special about my eyes in the mirror.

After living around five years with me, she took to bed because of malfunctioning of various body parts because of earlier long neglect, and in a year, she peacefully passed away in my lap, clutching to her lover’s photograph to her bosom. I got her cremated at Manikarnika Ghat as per her wish.

I had the consolation of giving her, at least in the last few years of her life some comfort and dignity as a woman and mother, at home with her daughter, and her love and attention. I put my mother’s treasured photo of Subbu into a small decorative frame and kept it by her photograph on my study table along with mine.

I would go and spend some time, once or twice every week, on the steps of Manikarnika Ghat by the Ganga where my mother had been cremated, to think of her. One day, an uncle, looking like a tramp, wearing a pair of creased and soiled jeans with a half-sleeve shirt with flying unkempt salt-pepper hair, came running from the top of the steps, shouting, “Kakoli, O’ Kakoli, my Kakoli….” I got startled and stood up.

But he stopped short of taking me into his open arms, stood transfixed, and blurted out sadly, “I am so sorry my child, to have startled you. No, you are not Kakoli. You just resemble her from a distance, but your eyes are not as lovely as hers. Also, you are too young, just a kid, to be my Kakoli. She would be around your mother’s age, late forties. Anyway, I know she is no more and the registers here confirmed that she has been cremated here. Sorry, my child.”

At once his looks struck a note. I guessed, perhaps, I had met my father Subbu. His age and neglect had ravaged his visage. But from his features, he seemed to be the exact grownup version of my mother’s heart throb in the photograph. Rising anger in me for the man, who had left my mother in a lurch, was choking me with abuses that I wanted to hurl to his face. He perhaps stayed away because of this ‘Kakoli’, and didn’t even respond to my mother’s distressed letter.

Had he another affair with ‘Kakoli’ after leaving my mother, Mouli, at Naihati? Or was it the name of his runaway wife whose body was cremated at Manikarnika ghat? I walked away from the ugly scene, leaving him to his devices.

Surprisingly, I found him there on the same spot on the Ganga-ghat each time I went there during my intermittent visits. As if, he was coming there and waiting for me the whole day, every day, just to have a look at me who had a distant resemblance with his Kakoli. The moment he would cast his eyes on me, his whole visage would light up with a rare shine, people associated such flushed state with epiphany-experiences.

But slowly, the man’s politeness and misery won me over. We became friendly. At least for my sake, he started keeping himself clean, washed, brushed and attired decently. He was not poor. He had just lost the fun of living. He was slowly opening up to me. He had a way of talking haltingly and disjointedly.

I had already learnt that his line was IT, the same as mine, and had collected information that he had been considered a genius of IT sector and he lived in Mumbai. I had to piece together what he said into a coherent narrative to understand it logically. Let me narrate his story as spoken by him, in first person, by stringing together his disjointed utterances and putting aside his intermittent fantasies and self-flagellations as far as possible.

Subbu’s Story -

I lived in Bombay, a kid of six by the name Subbu, with my parents and paternal grandma. My grandfather had passed away, I knew him only from his large garlanded portrait photo, hanging in our sitting room. He was white dhoti-kurta clad like any Benali bhadrolok, or a gentleman of Bengali Stock, that he was.

I studied in St. Joseph’s High School in Wadala located at a stone's throw from our bungalow by the Five Gardens area. I was enrolled as Subrat Mukherji, a rather grand sounding name for the little kid Subbu. During my initial days in school, when the teacher madam roll-called ‘Subrat Mukherji’, I would not respond until my bench-mate jabbed me in my ribs.

I was the only child of my parents. That made me sad and a lonely kid. My grandma was my only playmate those days. I was a nervous child. I presume, that made me stammer a lot and talk in a halting manner. In school days it brought me frequent punishments but later people in my vicinity considered it as a trait of my being a genius, a mannerism common to many super-intelligent people. Even ‘Mouli’ said so. (Here I, Anubhuti, would think, the fellow at least can recall my mother’s name!)

We lived in a rented old bungalow owned by a Parsee gentleman, Khosravi uncle, who was my father’s chum, a very close friend. The arrangement was a Pagree system of the Metropolitan Rent Rule. The Parsee uncle was not married and his parents had died long ago. He had no siblings or relatives. He would visit us in all festive occasions, enjoying it with us like a cousin.

Once the Parsee uncle fell very ill. We took care of him at our home and then put him to a hospital. During his hospital days, he expressed his desire to do a will of the bungalow bequeathing its ownership to myfather. But my father was a man of ramrod principles in matters of dignity and fair play. The Parsee uncle’s offer received no response from him.

My practical mother however was furious for my father’s non-committal gesture. But her ‘meow’ was silenced before my father’s ‘roar’, “Won’t it look like a quid pro quo for the little care that we are extending to him when he is so unwell?”

Then he would reason with my mother, “Listen my Lata. If I say ‘yes’, it would appear that all our care and attention for him is for acquiring his bungalow, which is not a fact at all. If I say ‘no’, it may hurt his dignity, as he is an honorable man. He may consider our care for him like a charity bestowed on a helpless man. He may be crushed under the burden of obligation. To keep quiet, saying neither ‘yes’ nor ‘no’, would therefore be the best course.”

I would feel proud of my father for not only taking care of our family dignity, but also caring for the dignity of the Parsee uncle, an outsider to our family. That left an indelible mark on my conscience, I think, and I have tried to live to that benchmark my entire life, a ramrod fairness. (Here, I, Anubhuti, would think, “Where was your sense of fair-play Subbu, when you probably left my mother, Mouli, in a lurch for your ‘Kakoli’?”)

Our relatives from my father’s side, lived at our ancestral place, Naihati, a small town in Bengal, on the bank of the river Hooghly, considered the same as holy Ganga. The small town was around fifty kilometers from the city of Calcutta. There lived my two married cousins, my father’s nephews, much older to me.

There we had a one-storey brick house on an acre of homestead land. The compound with a low boundary brick-wall had a lily-pond, coconut trees besides a few Mango and Chikoo fruit (sapodilla) trees. A riot of jasmine bushes kept the compound fragrant through the year. We had also a few acres of rice fields in the outskirts of Naihati. Both the house and the farm land were looked after by my cousins.

I would notice my mother not treating my grandma well. That often choked our household with sulks of my grandma. My mother’s behavior towards her was like a slow poison, doses of abuse every day. It was killing my grandma slowly. Finally, grandma expressed her wishes to leave Mumbai and live in our Naihati house. She brought it up very obliquely taking care not to hurt my father’s or my sentiment. But we two knew where the shoe was pinching.

I had just got promoted to my sixth standard. I sadly observed that all commiserations of my father with his mother and wife had failed. I had considered my father as the best negotiator who could reason with any adversary, and I would hold him almost equal to Don Vito Corleone of the ‘The Godfather’ fame, who could, the novel said, reason even with a dead man to rise from his casket. But for the first time I saw defeat writ large on my father’s face. He looked ill at ease, rather squirming with embarrassment helplessly before me, his son and his mother.

Finally, my father left for Naihati with my grandma to get her settled there safely and comfortably, perhaps, he wanted his mother to live away from his wife’s slow poisoning. When he returned a month later, he looked like having grown twenty years older.

After that he talked to all only the bare minimum, mostly in monosyllables. He had apparently left behind at Naihati three quarters of his heart with his mother, especially the quarters of his heart that loved food, jokes, family life, and his hobby of reading. I found him like a peanut shell without its nuts. He just lived with one quarter of his heart that kept beating to keep him alive.

Father would bring grandma to Bombay if she got unwell, get her treated by the best doctors, get her back to health, and drop her back at Naihati personally. I loved those visits of grandma, quite a few times a year. During those comings and goings, grandma would talk a lot about a girl, Mouli, almost of my age, who was adopted by grandma. In fact, Mouli was grandma’s granddaughter by distant relations and had become an orphan a few years earlier.

She would always have a few words of praise for the precocious child, Mouli, who was put by Grandma into a nice local high-school. She was studying in standard nine, a class lower to my tenth standard. She had stood first in her class when getting promoted from her standard eight to nine. Grandma would regale me with Mouli’s naughty antics.

When I had completed my Matriculation examination of the tenth standard, grandma was returning to Naihati from Bombay after a stint of treatment. I expressed my desire to spend that summer vacation with grandma at Naihati. My father was very happy, as he always wanted me not to forget my native Bengali roots and links. I accordingly boarded the Mumbai-Calcutta Mail along with my grandma for Naihati.

After getting down from train at the Howrah Railway Station, we took a taxi to Naihati sent for us by Mouli. When we arrived at the Naihati house, a dusky, slim, tall girl with chiseled features and a sweet husky voice, clad in a sari-blouse ensemble in Bengali style, opened the gate of the compound for us. There was no need for formal introduction. I knew she was Mouli, and she knew I was Subbu. My grandma had been sounding her about my accompanying her over the telephone before we departed from Bombay.

A smile of greetings was exchanged between me and Mouli, my smile was open and frank, hers, shy but with a hint of tease, as if saying, “Hello, smart Alec city boy! Keep your legs hidden. If I find one, I will pull it.” Her unspoken words didn’t escape my amused eyes. My silent mocking smile teased her back, “Let’s see how long you wear your ‘Plain Jane’ shirt sleeves. My name is not Subbu, if I will not bring the naughty little brute out in the open soon!”

The fragrance of a riot of jasmine bushes that perfumed the air, welcomed me and led me inside the compound and elicited a ‘Wah!’ from me. We entered the front room and a faint breath of jasmine was hanging in the air like an invisible mist, either filtering from the outdoor bushes, or emanating from a thick string of jasmines worn by Mouli in her hair. Defying my young scientific mind, I felt a strong magnetic force in Mouli for the iron contents of my inner being. For no apparent reason we looked at each other repeatedly and our eyes locked each time.

From the day one, Mouli took over to be my raconteur about Naihati town and my tease to keep me amused. She would tell me all that were of fun to her childish minds, such as pleasure of swimming in the Hooghly River, the incomparable taste of Hooghly Hilsa fish, eating the local spicy Kachori with juicy sweet soft Rasgulla etc.

When I said that fine bones of Hilsa fish were beyond me, Mouli teased, “Ish..ish.., my smart city boy!”, but then she added giggling, “The nibble fingers of this foolish small town girl would teach the dumb ones of the smart city boy the fine art of eating Hilsa.” In fact, the Hilsa brought us closer when, while looking for Hilsa bones in fish curry, our fingers entwined naughtily.

We became friends, and I kept a new name for Mouli that I would use between us only and extracted an oath from her not to divulge it to anyone, not even our grandma. She would jump into my arms whenever we were alone. Hilsa and hugs were our first steps of falling in love. Grandma would be vastly amused by our mutual liking.

One afternoon, grandma was visiting her lawyer. Mouli was home because of a local holiday in her high-school. She was tinkering around inside the house with some work grandma had given her and I was finishing a Bengali novel lying in a hammock on the outside veranda.

After the excitement of the climax in a situation of magic-realism, the hot and sweaty day drove me indoors to have a cool shower. Wrapped in a towel, I entered the semi-dark bathroom. Inside, I took the towel off and hanged it on a peg. I turned around to the shower-corner but had the shock of my life.

There stood a mermaid by the wall in the semi-dark. The mermaid’s torso was of a human-size silver-colored fish, topped with a woman’s face, as a mermaids looked in fairy tales. It had upper two flippers and it stood on its two tail-fins.

But my spell broke as eyes adjusted to the dark. It was Mouli standing, her lower half above the breast level wrapped in a wet white Turkish towel, giving the impression of a fish-torso in the dark, as did her hands and feet that of fish-flippers and tail-fins. Her coming out after her shower and my entering had coincided at the door. So, she had retreated back to the wall.

That moment served as our moment of reckoning. Inexplicably, Mouli’s towel slipped from its knot to the ground making her stark naked. Gasping in panic, she sat down in a heap, as did I did the same thing simultaneously to hide my nudity from her.

What followed next however was a heavenly course in any human annals that rewrote our destiny. The next one hour on the wet slippery bath floor was an awakening and ecstasy for both of us. Two mer-people, a merman with his mermaid, wallowed on a wet dark slippery floor in heavenly joy.

I would recall later that this tryst with destiny in our lives made us inseparable forever, binding us in an invisible bond of unexpressed commitment. We were head over heels in mutual love. Our coy behavior and magnetic attraction seemed to dismay the old relative; our grandma, who seemed happy as well as worried.

I returned to Mumbai after spending a month with grandma and Mouli. I had left a postcard size photograph of mine with her and carried to Bombay a similar photograph of Mouli as her memory. Years ago, my father had left behind three-quarters of himself at Naihati with his mother, but I returned leaving all of my heart’s four chambers with my Mouli back in Bengal. I felt terribly lonely and unhappy at Bombay.

A few days after my arrival in Bombay, I overheard my father talking to grandma over phone. I could make out that they were discussing about a match-making between me and Mouli for marriage. My joy knew no bounds.

But my spirits sagged when my father concluded, “Ma, Subbu is too young to marry now. He would need time to finish his studies and settle down. I agree with you, ma, it would be a very good match. But all in its own time, please.” But I hoped all would be well in due course.

Grandma came for treatment to Bombay, turned serious and was hospitalized. She passed away leaving us all heartbroken. Father sent a messenger to bring Mouli to take part in our family mourning and to stay with us to continue her studies as she had no support after grandma’s demise. But the messenger returned without Mouli.

He brought a very disturbing news. Mouli was not there and my cousins told him that after the news of grandma’s death reached Naihati, the maternal uncles of Mouli took her away. But after a few months of my worried waiting for news about Mouli, a news sadder than grandma’s death shattered me.

I heard my father reporting to my mother, “See Lata, the bad luck of the orphan. Her cousin uncles sold her for a price to a marriage-broker who in turn sold her to a rich man, Danwantari Das, in an Odisha village. Dhanwantari Das, a rich man of her father’s age, has married Mouli. What a travesty!”

I went berserk after hearing the news. I would know later that I suffered from a severe nervous breakdown and underwent a year long Psychiatric treatment to return to a state they called ‘lucid but wobbly’.

In fact, I felt I was an automaton humanoid, a digitized machine tool, a robot. I rejoined my studies. I restarted where I had left. My teachers were dumbfounded, “Subrat has developed capabilities of a genius. He had been just good at studies earlier, now his faculties are super-human. He seems having a supercomputer’s memory bank and the innovative power of the great mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. We presume, the medicines while repairing his brain have rewired it to greatness.”

I heard the praise but felt no jubilation. My parents were temporarily jubilant but slowly I noticed them talking with dismay. My mother was saying, “This Subbu is not our old Subbu, but a stranger. He is so indifferent and callous towards all except his studies. Perhaps, grandma’s death has brought the change.” Then I saw my father shake his head like a man absent there, and muttering to himself, “No, it is for Mouli.”

That very soliloquy of my father brought Mouli back to my mind and I cried and cried for days together missing my classes. I was allowed my ways. Tears were great healers. Crying nonstop helped to connect, less with the living world but more with a world of nostalgia and fantasizing, often, bordering the supernatural. My professors reported, day by day, my brain was getting stronger and pithier, more innovative. I had a supper connect with computers.

I was selected to enter the Computer Engineering degree course at MIT, Pune, and passed out as the topper of my batch, breaking all earlier records. I had another course on scholarship in USA with top results. Returning to India I joined a top IT company. I was called a walking, talking and thinking robot, knew nothing about real life, but all about hardware and software. My programing expertise for my company’s clients in India and abroad brought applause to my employers in Mumbai.

I cultivated my secret world behind everybody’s back, to which now had joined the souls of my Parsi uncle, my grandma, father, and mother. The last two having passed away, one following the other, when I was in USA. I had not come from USA to attend to their last rites because both of their souls came there to me in USA after their deaths and we had a gala time in my room.

In my secret world, Mouli was always there by my side. She would sit on an arm of my chair or on my lap, and would whisper me the solution when I would be racking my brain on a programing issue. It was strange, for she had not studied any computer course. But if I confided in anyone about her supernatural help, he took it as blabbering. So, I learnt to keep my experiences to myself.

In the meantime, Bombay had changed into Mumbai; and I had a meteoric rise in my IT company’s hierarchy to become its Managing Director in a little more than ten years. I had now to report to the founder- chairman of the company only. I didn’t know why, but various media reports would portray me as a cranky computer genius. Breaking a taboo of a superstition among IT engineers, I tackled hardware as well as software with equal dexterity like a rare Medicine-cum-Surgery-cum-Psychiatry expert in medical parlance.

I took my company to one of the best levels of excellence in the world digital arena. But I had little social respect in my neighborhood. My neighbors rumored that I walked all night in our rambling old mansion muttering to myself. In fact, I was suffering from chronic insomnia, and putting my sleepless hours to better use. I kept myself busy in creating new and advanced logic gates and composing algorithm in my mind for my software experiments.

Of course, I admit, often I discussed things with my Mouli who helped me in my advanced computer experiments. People took it as talking to space and the starting of madness

My bungalow lying in disrepair got submerged in a jungle of planted flower beds, trees and all-pervading weeds in its compound: dead, dying, growing, depending on seasonal and unseasonal rains. I had little time for those trivial details. I found this natural turn of events rather more interesting and to my liking.

Indoors, the house was kept clean and a little food was cooked for me by my old house-maid who was appointed as a young woman by my mother. The walls were peeling, windows boarded-up to prevent falling down out of disrepair. My neighbors, on their own accord, got my bungalow a new name as ‘Bhoot Kothi’, or ‘haunted house’, though its proud nameplate read ‘Khosravi House’, Khosravi being name of the original owner.

At around that most disturbed time of my life, when I had stepped into my late forties, I got news from one of my Calcutta contacts that Mouli, my heart throb, had passed away of tuberculosis at Banaras. I could not make out how and why at Banaras, because she had been married in Odisha? I was also told she had left behind her daughter who had joined an IT company at Banaras.

I was missing Mouli by my side for the last few months and was heartbroken. Now her absence by me, made sense. But why didn’t her soul come to the secret world of my grandma, Khosravi uncle, and my parents. I strongly desired to go and persuade Mouli’s soul at Banaras and convince her to come with me to Mumbai, now that she was free from her marital encumbrances.

I also, felt a strong urge to find out Mouli’s daughter at that holy city, she would carry at least some of Mouli’s magnetic powers for the iron contents in my inner being and would feel my presence in some uncanny way. I also decided to look for her in all IT related firms.

As both my two projects were likely to take time and attention, I begged my chairman for a year’s sabbatical, and he said, “Go ahead my boy, enjoy and know the life that lie outside the bits and bytes. You would be welcome back, anytime you decide to return. I have just chosen you as my successor in the company and the bequeathing deed, signed by me and all the directors and registered, is lying with our company’s law firm. It was supposed to be your surprise gift on your birthday next month. But as you would be away, here is a self-attested Xerox copy for you.”

Anubhuti’s Story Continues -

When I put together the odds and ends of the mad uncle’s story into a coherent chain, my guess, that he could be my biological father, became confirmed. But the name ‘Kakoli’, possibly the woman who made him ditch my mother, remained a blot on his character that I couldn’t overcome. I therefore couldn’t reveal to him that I was not only his Mouli’s daughter he had been searching but also, I was his own daughter.

He had failed to find Mouli’s daughter in any of the small and big IT firms around the city of Varanasi, because he had no references like her name, her father’s name etc. Only Mouli’s reference elicited little response. Also, his unkempt appearance and halting and mumbling way of talking were his bane. He would also avoid giving his real identity that could be of great help.

We met almost every other day at Manikarnika Ghat and spent friendly hours. The days he didn’t meet me, he would tell me, were ironically spent in searching Mouli’s daughter, i. e. me-myself, out of the holy city’s crowd. It pained me but ‘Kakoli’ still influenced me not to help him in his search.

But once his absence lingered on and on. The third day of his disappearance, I started a search for him in nearby lodges. I found him suffering from malaria and lying very ill in his bed in one decrepit lodge. Fearing the worst, I forcibly took him home. I put him in my outer room, in the same bed where my mother had slept. He was delirious with fever but sniffing the clean bed immediately reacted, “Kokoli, are you around?” I took it to be his delirious mind and ‘Kakoli’ made me angry again.

He recovered quickly. One morning he made tea in the morning before I left bed and carried the tray with our cups to my bedside in the inner room. To his call I got up and gratefully accepted the cup from his hand.

He sat down on a side chair to sip his tea. His eyes fell on the photograph of my mother by my own and young Subbu’s photos. I found his face flush with a rare light and eyes well up with tears. “Kakoli” he shouted at my mother’s photograph, got up, put his cup with a shaking hand on the table. He took my mother’s photo from the table and sobbed like a child over it, repeating, “Kakoli…. Kakoli…. Kakoli….”

He then looked at me and perhaps noticing the resemblance again and putting two and two together, he came to me with open arms. By then I had realized that Kakoli was the secret name that Subbu had lovingly kept for my mother, Mouli, because of her melodious voice. I responded jumping into his arms.

I whispered into his ears, “Papa”. His eyes went up in surprise. I told him, “My mama said you put me in her mermaid womb on a wet and dark bathroom floor, and she named me ‘Anubhuti’ as agreed by you both. She loved you to her last breath, lying and breathing her last on the same bed you are sleeping these days. That’s why my papa, you found its smell familiar, even the faint smell after the laundry. Perhaps love is like that.” He looked like the happiest papa in the World and simply said, “Anu, pack up, we are living. My sabbatical is over.”

***

The old genius is back in his den. As well his great organized and logical mind. Our bungalow in Mumbai has been added with many rooms and lot of living space, hosting around a hundred of dispossessed widows and above the big letters of ‘Khosvavi House’, the billboard of the bungalow has been painted with ‘KAKOLI WIDOW NEST’ with still bigger letters.

Our trust, in which I and my father are also trustees, finances the Kakoli Widow nest for their living with dignity. The widows self-manage themselves. We, father and daughter, live in a small flat, built over the bungalow. Subrat Mukherji is so busy these days in pampering and spoiling his new found little Anubhuti, yours truly, besides his ‘Kakoli Widow Nest’ and his chairmanship that he has little time for his secret world.

Prabhanjan K. Mishra is a poet/ story writer/translator/literary critic, living in Mumbai, India. The publishers - Rupa & Co. and Allied Publishers Pvt Ltd have published his three books of poems – VIGIL (1993), LIPS OF A CANYON (2000), and LITMUS (2005). His poems have been widely anthologized in fourteen different volumes of anthology by publishers, such as – Rupa & Co, Virgo Publication, Penguin Books, Adhayan Publishers and Distributors, Panchabati Publications, Authorspress, Poetrywala, Prakriti Foundation, Hidden Book Press, Penguin Ananda, Sahitya Akademi etc. over the period spanning over 1993 to 2020. Awards won - Vineet Gupta Memorial Poetry Award, JIWE Poetry Prize. Former president of Poetry Circle (Mumbai), former editor of this poet-association’s poetry journal POIESIS. He edited a book of short stories by the iconic Odia writer in English translation – FROM THE MASTER’s LOOM, VINTAGE STORIES OF FAKIRMOHAN SENAPATI. He is widely published in literary magazines; lately in Kavya Bharati, Literary Vibes, Our Poetry Archives (OPA) and Spillwords.

For days I had been romancing that fancy vase.

On my way to the office, every morning and evening as the bus slugged beyond the water works office to a stop, I eagerly looked out to see it was still there.

I never missed it. It sat right there on the pavement along with an assortment of other pottery. A family, nomads for sure, of three old women and two young men, was there. An old woman and a young man were in charge of sales while the other three were tinkering with the unfinished products.

They probably slept on the pavement, ate what they cooked there used the street tap for their daily routines. There was nothing remarkable about what they wore, so there was no way of knowing whether they ever changed, and they appeared to have never taken a bath.

I lived in a small apartment, all alone. My parents had gone forever and my wife had gone for good. After my office work, some of which I brought home, I cooked, managed my home, read the newspaper, and watched old Hindi movies.

One day at the lunch table, I mentioned the vase to Sharika, the computer operator, one of my very few friends. She laughed at me.

“Are, they look great for sure but don’t buy them. They will crumble to dust in a week. It is that plaster of Paris. You can buy better ones on Amazon seconds.”

“What is Amazon seconds?”

“Oh, there they sell goods which people have rejected and returned for no apparent reason. I have bought so much stuff from them and never found any fault. Not even once.”

“Do they sell vases?”

“Well, I don’t know. You will have to check.”

“Sounds good. I will try that.”

After that incident, I was very careful not to bring it up again.

Actually, I was in no need of a vase. No garden, no visitors and no time. What use was a vase for me?

But, I wanted that one vase like mad. It was like being in love with a plain homely girl. People may wonder why, at times you may also wonder why.

“The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of... We know the truth not only by the reason, but by the heart.”

Yes, it is Pascal. I had studied an essay about it in college.

Days went by and one day I got down at the waterworks to check out the vase. I had some cash with me. I thought that should be enough.

It was not enough. The old woman spoke some language I hadn’t heard before. But she told me the price in perfect English. It was too high. But, I would have bought it without bargaining, paying the same amount, if I had that much with me.

I checked my purse and found I was short of over a thousand rupees. I walked away without looking back at the woman or at the vase. It was like saying bye to some dear soul at a railway station.

The whole of next week, the vase possessed me. I thought about it the whole day and eagerly stared at it as my bus went past it. It had become a towering city monument which everyone revered.

One night I had a dream in which my mother came home with an empty flower pot. My father liked it and he immediately pulled out a couple of marigolds and planted them in that pot. Both of them tended to it like a baby. I was sitting atop a wall munching some snacks.

The next morning I was shocked to see the nomad family packing up. Most of the wares were gone, and a young man and a woman were also missing. The old woman who had spoken to me, the other old woman and one of the young men were still there. That vase was still there. I heaved a sigh of relief.

At the office, I could not focus on my work. I thought of feigning a headache as an excuse to leave. I didn’t have to. By lunchtime, I did have a headache.

I applied for a half day of casual leave. The section officer gave me a paracetamol and told me to wait till three o’clock. I could go home after that without wasting a half day's leave, he said. I thought that was fine and thanked him.

The pill worked fine and by three o’clock I left my office. I rushed to the bus stop as if I had to visit a dying patient at the hospital.

I got down at the waterworks. They were still there. I heaved a sigh.

They had packed up and were ready to leave. I could spot my vase wrapped in a rag.

My vase? I had not yet bought it, I reminded myself.

I had a hard time telling them I had come for that vase. Finally, they got it. In mock seriousness, the old woman gestured to me that it had gone. The others joined her in her laughter cracking more jokes about me.

Finally, she whisked it out of the rag like a magician and I faked an expression of surprise to thank her for keeping it for me. I told her through gestures that I still had to go to the bank and collect some money to buy the vase.

They together made it clear to me that I had to return soon. Their train was at five o’clock and it was already four.

I rushed to the city centre where I knew there was an ATM.

I went to two ATMs, but they didn’t work. I ran around for a third one. It was like all the ATMs had vanished by some witchcraft. I panicked.

A third one too failed to pay me.

I caught an autorickshaw and went to an ATM near my bank.

There was a queue. I stood as the fifth person.

My heart was pounding. My BP was skyrocketing. I thought of murdering all the four of them who stood before me in the queue.

Finally, I got the money. I was so happy I almost fainted.

It was really late. The pick-up van would have taken them to the railway station.

I caught an autorickshaw. I told them to go to the railway station by the waterworks road.

“That is a long route, sir. If you are catching the fine o’clock, you will not make it.”

“Just do it !” I shouted at him.

He shuddered as if he was confronting a murderer. Well, he was. I was so desperate.

They had left. The pavement was deserted.

For me, it was a whole empire which had vanished.

I asked the autorickshaw driver to hurry. He turned around and stared at me as it to ask: Didn’t I tell you dumbo?

At the railway station, I checked the platform number. The third one. I had to cross the overbridge. No time to buy a platform ticket.

I ran like the wind, past stares from other passengers. At the bridge I saw the signal changing.

I don’t know how I went down the stairs. I ran down the platform towards the general compartment along the slowly moving train.

Now I was running along the general compartment, cash in hand looking in through the window.

The woman was sitting on the floor. She was still clutching the vase wrapped in rags. The train was gaining speed.

She saw me and got up with the vase. She came to the door and offered it to me. All the kindness in the world was there on her face.

But the train was now rushing away from me. I tumbled down on the platform, still clutching the cash.

The woman was now waving at me. The train was about to disappear totally,

I waved back at her.

Soon it was all a blur. I sensed tears rolling down my cheeks.

Two porters rushed towards me and helped me to a platform chair.

“Did you miss the train, sir?”

“No.” I smiled at them. “I missed the flight.”

They joined me in my laughter as if they understood my wisecrack.

Sreekumar K, known more as SK, writes in English and Malayalam. He also translates into both languages and works as a facilitator at L' ecole Chempaka International, a school in Trivandrum, Kerala.

“Here is an unusual request, or, call it a challenge, if you prefer” my friend, DSP Harish Chander, was on the phone.

As a child specialist, I am used to my friends and family contacting with concerns over children’s health issues. Harish is my college friend, who is the local Deputy Superintendent of Police. His request was hard to categorise. Firstly, It was not about a child, known to either of us. Secondly, it was not exactly a health issue, as we know it. If it qualified as a health concern, it certainly was not a common one: fever, chill, vomiting or a rash. It was about Pinky, a nine year old girl from Sishu Bhavan, the local orphanage.

I have been visiting Sishu Bhavan on a regular basis, attending to ailments of the children it housed. Over the years, I have got to know the Matron, Miss Joseph, rather well. Typically, I got a call directly from her, if a situation there needed urgent attention. As she had not called me about Pinky, I sensed, the problem, Harish was calling about, was not straight forward.

In the local news, I had read about a recent conflagration in the town. A large godown had been burnt down, with everything in it reduced to a rubble. Although it was by no means certain, rumours were rife that it was the local liquor depot. No one knew, how much money went up in flames; the estimates varied wildly. Intriguingly, the cause of the fire was unclear. Some said, it was an accident but many thought, it migh be a deliberate act. If it was an act of arson, speculation over the motive and the identity of the perpetrator became fodder for gossip in the town.

The mystery surrounding the fire entailed another twist. Police had apprehended from the scene, two suspects, both young men, who hailed from the neighbouring village. They had been missing for a few years without any trace until they were caught icy the police fleeing from the scene of the fire.

“You must have heard of the fire in the warehouse in the town,” Harish said by way of introducing the problem. “Pinky, a young girl, from Sishu Bhavan, had absconded from the orphanage in the night of the fire and was found wandering near the godown in a daze.”

“Is she all right? I hope, she did not sustain any injury or suffer any burns from the fire.”

“No, there are no worries of the kind. She is safe and free from any injury, whatsoever.” Harish reassured me.

“What are you calling me for, then?” I implored.

“When Pinky was picked up by the police, they were relieved to find her alive and unhurt. She had been registered as a missing child and they were worried about her safety. In this day and age, you always imagine the most horrible fate for missing girls. Most are never found. By the time the alert is raised, they would have been smuggled out to somewhere completely out of reach of the local police. If they are ever found, it is usually their brutalised body.”

“So, what is the problem with Pinky?”

“She looks all right, if not hundred percent normal. She is certainly not in distress. There is a strange look on her. Mysteriously, she is mute. She has not uttered a word for last 24 hours.”

“Is she fine otherwise?”

“Yes, she walks, eats, plays and sleeps well; no problem at all. But she is totally mute.”

“She is probably in a state of shock. The scene of fire must have overwhelmed her.”

“Yes, that is what we suspected too. We thought, we must allow her time to recover from her shock. But, as time has gone by, we realise, Pinky’s case is bizzare.”

“Perhaps, she needs more time to recover from the trauma.”

“But there is a look on her face, difficult to describe. You have to see her to appreciate it. From her look, you think, she would burst out talking any minute. What is holding her back is hard to guess. Perhaps, you can make her talk.”

I was beginning to appreciate the problem Harish was struggling to convey. But my first thought was, this was a job for a specialist and beyond my expertise. But Harish insisted that I should at least have a crack at it. In any case, child psychiatrists are not easy to find, except in metropolitan cities. Rather than continuing with this telephone interrogation, I decided to visit Sishu Bhavan and meet Pinky.

xxxxxxxxxxx

Pinky turned out to be an ordinary looking girl, average in height. Dressed in a frock with large white polka dots against a red background, she had her hairs braided neatly in one ponytail. She had a confident gait with brisk movements. If you were not told that she was mute, you would not suspect it from her demeanour. Strikingly, she showed no emotion at losing her faculty of speech; it did not bother her at all. Far from showing any sign of distress, she was carrying on, as if nothing had happened.

I collected from Miss Joseph, all that was known about her background. I was hoping, this would give me a hint of what made her response to the fire so dramatic. Unfortunately, information on her parents or her past life was sketchy. She was picked up by police from a railway carriage and nobody ever claimed her as a missing person. She herself spoke little about her parents, except that she had lost both of them, in quick succession, a few years previously. She had been staying with an uncle, who never made her feel welcome in his house. One day, Pinky did run away from home and travelled by train hundreds of miles, surviving by begging and kindness of strangers. She was so distressed, talking about her family, that the kindest thing they could do was to avoid probing into her past.

Although she revealed little about herself, she took a keen interest in the lives of all other children, In this regard, she was ahead of her age , showing a maturity uncommon for a girl of nine . Considering the horrors of her home life, her behaviour in the orphanage was surprisingly normal. She rarely showed any bitterness and her mood was always upbeat. Looking back, there was no discernible change in her behaviour or mood, leading up to her sudden disappearance on the evening of the conflagration.

All my attempts to make her talk proved futile. So, I decided on an alternative approach, communicating through pictures. I left some sheets of blank paper and coloured crayons with her, while I was discussing some other issues with Miss Joseph.

When I returned to Pinky after a while, she had drawn an outline of what looked like a house. It had a slanting roof and a chimney on the top, and a door and windows in the front. Inside, there were three figures. and from their contours, it looked like the picture of two adults and a child.

I returned to Pinky the next day for resuming our pictorial communication. It was gratifying to see Pinky had worked on her drawing. But, it looked as if she had smudged the neat sketch from yesterday with wavy blotches of bright red. No amount of coaxing or cajoling would yield any hint on what she had drawn. The following day, she had added something more to the her artwork. She had drawn, in bold lines, a bigger box like structure around the house. There was more red colour; now they were all over the paper. You had to peer really close to see the tracing of the small house, she had drawn in the beginning. There was nothing visible any more of the original neat human figures inside the house.

This was an encouraging sign; she was clearly saying something, though not in words. It was now up to me to decipher the symbolism of her drawing. Probably, this was her account of what she witnessed in the night of the fire. Although I remained hopeful, the hints were still far too cryptic.

xxxxxxxxxx

Before my next session with Pinky, I wanted to share my progress or the lack of it with Harish. At the same time, he gave me an update on the two suspects held in custody. Notwithstanding some promising signs, I was nowhere close to getting Pinky’s testimony on the fire. Perhaps, it was time for me accept that the task was beyond me. In any case, I suspected at the outset that it was a job for a super psychiatrist, not an average child specialist.

“What do the young men say about the inferno?"

“They deny any involvement in the warehouse fire. They claim , they were simply passing by. They came across nothing suspicious at all and deny any knowledge of who might have done it as they saw nothing.”

“Are there any other suspects?”

“No, but the issue with the young men is complicated. It is not their role in the inferno, which is important now. Search of their bags showed documents on bomb making. Police suspect, the duo might be a part of the local Naxalite gang. In fact, the focus of investigation had moved on from the fire to their involvement in terrorism.”

“What about the case of the fire; is it closed?”

“Not exactly, but it is no longer a major event in eyes of the police. It has been overtaken by the new angle of terrorist links. Fires like this are far too common. Possible links with terrorism have pushed the investigation to a different level, up by several notches.”

“You mean, the case of fire is left unsolved?”

“If so, this will not be the first of its kind.”

“I have been working on some clue from Pinky towards solving the incident of arson. And, I think, I am getting somewhere.”

“That will be a bonus. But your primary task was to make Pinky talk.”

I was back at the orphanage with Pinky, for, what I thought, would be my last session. There were clues in her drawing to something she witnessed that night, which could potentially solve the puzzle of the arson. So, I decided to make one final attempt, before I admit my failure and cease my involvement. I looked at her drawing and could not find any major change from yesterday.

I sat down on the chair, waiting for Pinky to add more to the drawing, which would give some clue to work on. But she was quiet and still, seemingly in no mood to do any more drawing. I pretended to immerse myself in the newspaper, deliberately blocking me out of her view by the paper. I was secretly hoping for more revelations to come from her drawings, if she was not distracted by me.

I suddenly heard Pinky, screaming, “Sir, they did not do it.”

I jumped out of my skin. Startled by her shriek, I looked at her asking, “What did you say, Pinky?”

“They did not set fire to the godown.” She was pointing at the photo of the arrested men on the newspaper, which I had just put down on the table lying between us.

“How do you know?”

“I know, because I did it.”

I scanned her face for some visible emotion, when she repeated, “I set the godown on fire.”

I turned my gaze at the drawing she had been working on over last few days. Although the paper, by now, was almost covered with red, I remembered the neat contours of the house and the picture of three people inside and a large featureless box surrounding it. The house looked like a family home and the bigger box resembled a warehouse. The central figure of her drawing, between the two grown-ups, looked like a child. That must be Pinky, I thought. Then, the wavy blotches of red perhaps represent the fire, starting in the family home and spreading to the godown.

I wanted to put my theory to test and asked her, who was the child in her drawing. She pointed a finger to herself. Next, I asked what the big box like structure was and to my satisfaction, she replied, “The godown.”

While I was mulling over my next line of questioning, she embarked on a monologue.

“My father was a caring man and loving father, except when he drank too much. The problem was that he was drunk most of the time. Liquor at the end killed him and destroyed our family. My mother killed herself and I was left an orphan. After coming here and talking to other girls, I realised I was not alone, in my misfortune. Liquor has been the constant villain, wreaking havoc in lives of so many honest and hard working families.

On our occasional day trips, we used to go past the big building and I learnt, it was a godown, for storing things, before they are distributed far and wide. Someone told me, it was a liquor depot. Since then, every time, I passed by the structure, I could feel the rage burning inside me. Gradually, a desire to destroy it grew and my restlessness did not ease until I decided to burn it down.”

“Are you ready to confess to the police?”

“Yes Sir, but not before these men are set free. You have to believe me, they did not do it.” again pointing to the newspaper.

“By telling the truth to the police, you would have done your duty. Don’t worry about them. If they are innocent, they would be set free anyway.”

“No, Sir, you are a gentleman and I trust you. When it comes to the police, it is a different matter. So many innocent people suffer in the hands of police, simply because they happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I know the police quite well. I went to them first, when my uncle tried to force himself on me. They did nothing. The day, I ran away from his house, I went to the police again, hoping they would help me. But they turned out to be worse than my uncle. I was lucky, I managed to escape from their clutches and I vowed I would never go to police again.”

On one hand, I was relieved to see her talking, although her story was heart breaking. Nevertheless, her insistence on the innocence of the suspects left me baffled.

“Who are these young men, by the way; do you know them?”

“Sir, you are a man of influence and you have high connections. Otherwise, the police would not have entrusted you with this delicate task.” Sensing my scepticism, she continued, “Take it from me, Sir, they are good people. What makes you think, they are guilty of anything?”

I was beginning to appreciate her deep insight into the complicated workings of police in the real world. I did not expect it from a child of her age. But, she was not an ordinary child. She had a maturity, foisted upon her by cruel fate. Nonetheless, I could not see how these two men in custody fitted in her version of the fire. Something was amiss with her account; there was probably more to what she had revealed so far.

Her furtive glances at the newspaper photograph continued, fuelling my suspicion that she had not told the whole truth.

“Do you know these men, Pinky? Who are they?” I repeated my question.

“No, I did not know them until the night of the fire. I met them for the first time at the fire scene. But, I know, they are good people.”

I waited for the next revelation from Pinky.

“They must be set free. I have given them my word. I promised them……”

“What word? What promise did you make to them?”

“I had planned it carefully. I set out that night, fully prepared to burn down the godown. It was the storehouse for the poison, that had killed my parents and destroyed my childhood. I could not rest until I did something about it. Before I could reach there, from far I saw it was already ablaze. I could not believe what I was seeing. The flames were high, the heat was fierce and the fire was blinding me. I had no idea, the fire could be so enormous; I ran in blind panic. That is when I saw these men, who were also running away from the scene.

They could have hurt me or even killed me, if they wanted. But they were genuinely worried about my safety. They told me that the godown was their enemy number one. They knew of countless men whose lives were blighted by drinking. Horror stories of liquor destroying families and ruining marriages were common place in their village. Demolishing the godown, they considered, was their civic duty and they had set it ablaze as a service to the public.

Everything worked perfectly to plan. I was all set to burn the godown and was certain to accomplish it if they had not beaten me in getting there first. It was as if they had read my mind and carried out my wish. As the plan was mine, I am responsible for the act, no matter who executed it.

I promised them, I would take the blame for the fire. I asked them to run away as fast as they could, But it seems, they were not fast enough and could not get away. As they did it for me, I must, in return, keep my promise and surrender to police. In the court, I will explain to the judge why I went down this path. At least, the judge should have some sense of justice and he will understand.”

xxxxxxxxxxxxx

“My confidence in your skills has never betrayed me.” Harish was congratulating me.

“What about the two young men in custody?”

“I don’t know, what evidence police have gathered, towards their links with Naxalites, which is now the focus of investigation.”

“But, we know, what constitutes a terrorist act is open to interpretation. As per Pinky they did look like decent people, certainly not dangerous.”

“The investigations are still at an early stage and no decision on charges is made yet.”

“As you said, godown fires are mostly accidental, from faulty electrical connections. There was no death or serious injury in this fire. As to these young men, their guilt, if any, may be a matter of opinion. Pinky says, they have rendered a valuable public service.”

Harish fell silent. But, I continued, “You wanted me to make her talk. I have done my bit. Now, Pinky has spoken; you must listen.”

September 2022

Dr. Ajaya Upadhyaya from Hertfordshire, England, is a Retired Consultant Psychiatrist from the British National Health Service and Honorary Senior Lecturer in University College, London.

THE EXQUISITE BLISS OF DUNKED BISCUITS

Ishwar Pati

‘Dunkin’ Donuts’ is a famous American chain of coffeehouses. It originated in Boston shipyards in 1950 serving coffee and doughnuts, a quick and cheap lunch option for the shipyard workers. Take a doughnut, ‘dunk’ (i.e. dip) it in hot coffee and eat it.That’s how the name stuck. A rustic practice of dunking doughnuts in coffee made an enterprising young man realise his American dream! Unlike the boastful Americans, the British are stiff upper-lipped about their own custom of dunking, though Queen Victoria herself was said to enjoy dipping her biscuits in tea, a German custom inherited from her younger days.

I love dunking my biscuits in tea to make them soft on my palate. But my wife frowns on what she calls a ‘dirty’ habit. “You are such an uncouth pig!” she hisses, turning up her nose when I drown a biscuit in my tea! It reminds her of a drowning man flailing in murky waters, she says. I adore the way she twists her face when she says that. I wish I could bequeath this ‘rich’ practice of dunking to my children, notwithstanding my wife’s distaste. But she would hear nothing of it. Isn’t it enough, she thunders, that she has to tolerate one pig in the house? Do I want to convert my home into a pig sty?

In course of time our children have grown up, got married and produced their own kids. I may not have been able to‘brainwash’ my children.

But nothing prevents me from grooming my granddaughter as an ‘uncouth dunker’! She looks bored with her mandatory cup of milk anyhow. I made my move as she came out while I was sipping my morning cup alone in the garden. I asked her to touch the outer surface of my lukewarm cup. She hesitated before tentatively extending her hand. At the last moment she drew her arm back, giggling with the challenge. Again I asked her and again she extended her small fingers. When her skin made contact with her mug, she withdrew instantly with a cry. But soon her curious fingers returned to make more exploratory touches. I took a chocolate biscuit, dipped it in the tea and offered it to her. The attraction of chocolate was too great and overrode all other concerns. She snatched the biscuit from me and bit into it. Yummy! Sounds of satisfaction emanated from her throat. I had won!

But my triumph was transitory. Who should walk into the garden just then? My wife! Needless to say, she succeeded in depriving even the next generation of that uncivilised but heavenly bliss of dunking biscuits in tea.

Ishwar Pati - After completing his M.A. in Economics from Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, standing First Class First with record marks, he moved into a career in the State Bank of India in 1971. For more than 37 years he served the Bank at various places, including at London, before retiring as Dy General Manager in 2008. Although his first story appeared in Imprint in 1976, his literary contribution has mainly been to newspapers like The Times of India, The Statesman and The New Indian Express as ‘middles’ since 2001. He says he gets a glow of satisfaction when his articles make the readers smile or move them to tears.

A CUP OF SUGAR

Chinmayee Barik

(Translated from Odia by Ajay Upadhyaya)

The calling bell rang when I was in the bathroom. I was in no position to attend to the door immediately. Annoyingly, the bell rang again. I was forced to run to the door, hastily wrapping myself in a towel, with my wet hair loosely held together in a clip. Holding the door slightly ajar, I peeped out. The face at the door was not familiar; a young man in his early twenties was standing with a cup in his hand.

“What do you want?” The irritation in my voice was hard to hide.

“Could I have a cup of sugar please?” He stood there, rubbing his eyes, as if he had just woken up from sleep. Then, he greeted me with a Namaskar*.

“But, do I know you?”

“I have just moved into the flat next to yours. I am yet to fully unpack my luggage and I can’t find the sugar jar. Went to buy some sugar, but the shop is closed. I get a severe headache if I miss my morning cup of tea. Hope, this isn’t too much trouble.”

I was not sure how to respond to this unorthodox introduction from my new neighbour. Nonetheless, I picked the cup through the open door and shut it before turning to the kitchen. I returned with a cupful of sugar and passed it across the slightly open door and shut it back with a thud. The clock on the wall announced the time as quarter past five. I had to hurry and finish my morning ritual in time for my office. When I was walking briskly to the bathroom, I slipped and fell.

The backache from the fall lasted for the next four days. My resentment was directed at the young man, whom I held responsible for this accident. I never saw him again in those four days; he simply disappeared. Today’s youngsters have no sense of manners, I lamented. I enquired about him with a few of our neighbours, but no one had any idea of his whereabouts. It was better, I thought, to keep quiet about the incident.

A month passed by. One evening, at about eight, suddenly, I heard some sound of activity coming from his flat. I listened intently to confirm that I heard it right. Yes, it was unmistakable, he was in, perhaps, doing some cooking; the clattering sound of pots and pans was coming through the walls. With the hope that soon he would be returning my cup of sugar, I kept waiting. But I was wrong; on the contrary, he was back, after a couple of days, ringing the bell, this time, to briefly borrow the gas lighter. Apparently, his lighter had broken down. While I handed him the gas lighter, I could not help thinking of the cup of sugar, half expecting him to at least mention it. But no, there was none. He simply handed back the gas lighter and left. Although a cup of sugar was no big deal, his behaviour struck me as distinctly odd. I used to see him occasionally in the lift, when he would treat me like a stranger. But he had no hesitation in turning up at my door, again and again, asking for small items, like vegetables, cloves, mosquito coil, a polythene bag or a ballpoint pen. Strangely, there was no sign of him returning any of them. “Was he taking me for a ride?” I wondered. With time, as the list of items became longer, my sense of irritation towards him grew.

On twentieth of March, Mr Mishra was celebrating his son’s birthday. The entire colony was invited to the party. I don’t enjoy big or noisy parties. But Mr Mishra was insistent on my coming, so I reluctantly did attend the party. As expected, the venue was crowded. The birthday cake cutting was already over and dinner was about to be served. The guests made a beeline for the food with a plate in hand. I did not fancy standing in a queue and after handing over my present for the birthday boy, I was about to exit, when the young man caught me. He enquired if I had had my meal. When I told him that I would rather skip the dinner because big crowds made me uncomfortable, he offered to fetch my meal to a table nearby. I politely declined his offer but, ignoring my plea, he marched across to the food hall. So, I had no choice but to wait fro him at an empty table. He returned promptly with two plates of food, followed by two glasses of water. While we ate silently, I could see all the eyes of ladies in the crowd focussed on us. I felt uneasy by this glare, as if I had been caught committing an offence. Anyway, we carried on and finished our meal. As he walked away with the used plates, a group of ladies led by Mrs Bose descended on me. They were inquisitive about how I knew the young man. When I told them, he was my new neighbour in our block of flats, they did not seem to believe me. They kept probing as if he was more than a mere acquaintance, perhaps a relation of mine, as we shared a table for our meal. I found their innuendoes irksome and asked them to come straight to the point.

Finally, Mrs Bose gave me the scoop about the young man. He is Hrideyansh, a film actor. He used to work in Hindi films but he is now trying his luck in Odia film industry. No doubt, he is handsome, but his vanity knows no bounds. “Once, while returning from the market, I was looking for a lift in his car but he pretended not to see me. God knows, what film he is busy making, but he is puffed up in conceit.”

After listening to the ladies, I cast my gaze towards him. He was washing his hands at the time. Oh, yes, he is indeed good looking. How didn’t I notice it before? Anyway, I kept my thoughts to myself and left the party. On the way back home, the sugar incident kept returning to my mind.

While I was unlocking the door to my flat, I heard a commotion nearby. When I looked around, I saw Hrideyansh engaged in a heated conversation with someone. I figured out, it was his landlord, who was demanding an immediate payment of two thousand rupees towards his outstanding electricity bill. Hrideyansh was negotiating with him, promising to pay up in two days time. As I approached, I could see him lowering his head in embarrassment. Even, I felt uncomfortable with this situation. I took out two thousand rupees from my purse and quietly handed over to the landlord. After he left the scene, I indicated to Hrideyansh that he could return my money at his convenience. He did not utter a word but his eloquent eyes spoke of his gratitude.

xxxxxxxxxxxx

Five months elapsed. The saga of the cup of sugar gradually faded from my mind, but the matter of money didn’t. It was difficult to write off the sum of two thousand rupees, which was never returned. It was disconcerting enough to make me consider confronting him directly to ask for the money. To this end, I walked up to his door a couple of times but returned without ringing the bell. It seems, he was not home most of the time anyway and we never had an occasion to meet. I tried to console myself that two thousand rupees wouldn’t really matter in the end. I should just forget it and he would have to live with the debt on his conscience.

On that day, I had a splitting headache. I returned home early, took some strong pain killers and slept off earlier than usual. I woke up around 11 at night and could not get back to sleep. I turned on the television and flicked channels, looking for something to watch. I settled for a ghost film; it kept me engrossed and I lost track of time. This is when my concentration was broken by the ringing of the door bell. It was quite late, about one o’clock in the night. I was somewhat alarmed by the bell and went to check through the keyhole. When I saw Hrideyansh at the door, my anger shot up and I lost my last shred of decency and etiquette. I jerked open the door. There he was standing, unsteady on his feet. “Is he drunk?” I wondered. My rage now reached its peak. I screamed at him, “You rascal, what do you want now? Vegetable, sugar or money? Don’t you have any shame, turning up so late in night asking for things you never return?”

He was about to say something but I slammed the door on his face. It seemed, the ghost in the movie, I was watching, had taken possession of me. The sight of him was enough to let loose the demon inside me. Incandescent with rage, I gulped a glass of water and retired to bed, without switching off the TV. When I woke up next morning, it was already late. The TV was still blaring. I rushed into the bathroom to get ready for office. When I opened the door, I was surprised to see two thousand rupees lying on the floor. It seems, it had been pushed through the gap at the bottom of the door. As I remembered the incident from last night, I could not help feeling embarrassed by my own behaviour. After locking my flat, I looked at the flat of Hrideyansh, which too was locked. Perhaps, he has gone out already. I thought, I must apologise for my rudeness, on my return from office in the evening. That day, I remained rather preoccupied in the office.

In the evening, I saw his door, still locked. Perhaps, he had not returned home, I thought. Anyway, one day, I will sure meet him and hope he will accept my apology, I said to myself. But he was never seen again. I gathered from his landlord that he had ended his tenancy and was gone for ever. Although my first reaction was “Good riddance,” a sense of void soon enveloped me. From time to time, I would hear the door bell ring but when I rush to the door, there would be nobody.

In life, we can’t expect everyone to like us all the time. But we invariably need someone to nullify the loneliness in our life. Even if it is mainly headaches, they bring, perversely that could lend a purpose for living to a bankrupt existence.

Hrideyansh never returned. I had no contact address or phone number for him. But my waiting for him did not end. One day, suddenly, I heard rattling noise coming from his flat. Expectantly, I rushed to the door and pressed the bell. But it was not Hrideyansh; a new tenant had moved into the flat.

Gradually, I gave up all hope of seeing him again. With passage of time, I was coming to terms with the situation. But, it all changed one day, when upon returning from office, I found an elderly gentleman waiting for me at the door. He looked at me with knowing eyes, and said, “You are Rachna Madam, Aren’t you?” When I nodded in affirmative, he looked me up. I was slightly discomfited by his scrutiny and said, “Sorry, I can’t somehow place you.”

“You do not know me, but I know you. I am the father of Hrideyansh.”

I promptly invited him inside the house. He carefully sat down on the sofa. As he sipped his tea, he handed me a large packet, saying, “This is for you, from Hrideyansh.”

The bulk of the unexpected packet stood out. “Where is he now?” I asked him.

“He is at home, recovering from a fractured foot, he sustained in an accident.”

“Why did he leave this place so abruptly?”

“He simply made up his mind to run a restaurant in the village.”

“What! I thought, he was into film making.”

“Life does not always unfold as per our wish. We have to adapt to its vagaries and learn to manage what is meted out to us. He was so passionate about acting that I didn’t have the heart to raise any objection, let alone put barriers in his path. But he himself has now decided to return to the village. Yes, he has told me everything about you. I am sure, he was quite a handful during his stay here. Your patience and understanding is admirable; you not only put up with all his antics but you came to his rescue, in his hour of need, as well. I can’t thank you enough for all that you have done for him. Now he has permanently relocated to the village. As I was visiting the town today he requested me to bring this across to you.”

He soon left my house, as he had to attend to some other business in the town. I could not wait to open the packet, he left behind. Inside the packet, I found everything he had borrowed over the span of his stay. At the sight of the packet’s contents, I almost cringed. How mean it was of me to chastise him for these trivial articles! Perhaps, I was too harsh in judging his character; he had meticulously returned every item, with the singular exception of the cup of sugar. While I was stroking the contents of the packet, a letter dropped out. It was addressed to me and I hastily opened it.

Madam,