Literary Vibes - Edition CXLIX (31-Jan-2025) - SHORT STORIES

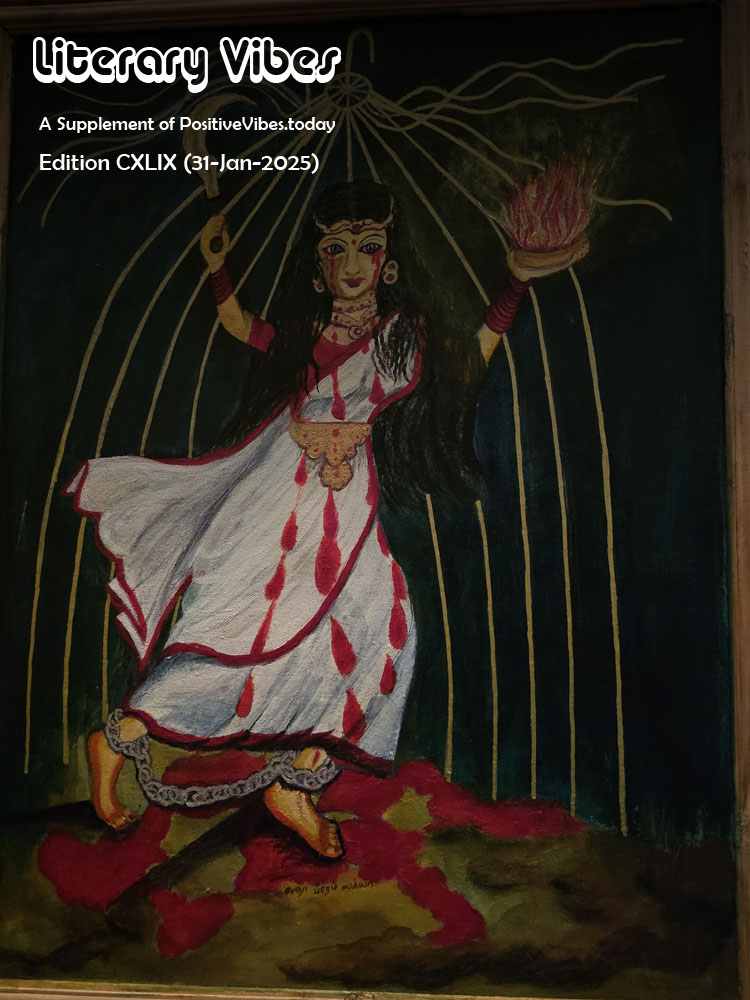

Title : The Woman Within (Picture courtesy Ms. Latha Prem Sakya)

An acclaimed Painter, a published poet, a self-styled green woman passionately planting fruit trees, a published translator, and a former Professor, Lathaprem Sakhya, was born to Tamil parents settled in Kerala. Widely anthologized, she is a regular contributor of poems, short stories and paintings to several e-magazines and print books. Recently published anthologies in which her stories have come out are Ether Ore, Cocoon Stories, and He She It: The Grammar of Marriage. She is a member of the executive board of Aksharasthree the Literary Woman and editor of the e - magazines - Aksharasthree and Science Shore. She is also a vibrant participant in 5 Poetry groups. Aksharasthree - The Literary Woman, Literary Vibes, India Poetry Circle and New Voices and Poetry Chain. Her poetry books are Memory Rain, 2008, Nature At My Doorstep, 2011 and Vernal Strokes, 2015. She has done two translations of novels from Malayalam to English, Kunjathol 2022, (A translation of Shanthini Tom's Kunjathol) and Rabboni 2023 ( a Translation of Rosy Thampy's Malayalam novel Rabboni) and currently she is busy with two more projects.

Table of Contents :: Short Story

01) Prabhanjan K. Mishra

TO JAYANTA SIR, WITH LOVE

02) Sreekumar Ezhuththaani

WATER WATER EVERYWHERE

03) Ishwar Pati

CYCLONE IN A TEA CUP

OVER THE WALLS

04) Sujata Dash

A QUIET SUMMER EVENING

05) Snehaprava Das

BLUE UMBRELLA

06) Bidhu K Mohanti

50TH YEAR, WOW!

07) Anita Panda

NAKSHA (PLAN)

08) Minati Rath

A WINTER EVENING AT ROURKELA

09) Deepika Sahu

LIFE LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE NEWSROOM

10) Shri Satish Pashine

THE CLOUDS ON THE MOON

11) Ashok Kumar Mishra

THE SPARK OF LIGHTNING

12) Hema Ravi

MUSIC IN LIFE

13) Surendra Nagaraju

JAMMI

14) Rekha Mohanty

MAGNIFICENT MAYURBHANJ

15) Mr Nitish Nivedan Barik

A LEAF FROM HISTORY: CELEBRATING A WOMAN, WHO BROKE BARRIERS AND ROCKETED INDIA’S FAME TO THE SKY!

16) Dr. Rajamouly Katta

POET

17) T. V. Sreekumar

SEVENTY PLUS SUMMERS

18) Sreechandra Banerjee

RHYTHMS OF THE HEART

19) Dr. Mrutyunjay Sarangi

MY FRIEND DIGAMBAR AND HIS DEAD SON

Prabhanjan K. Mishra

Jayanta Sir, the colossus who strode the spans of English poetry, the best ever among all the poets in India and outside, young and old, now or earlier; the Jayanta Mahapatra from Cuttack, Odisha, India, simply ‘Sir’ to many like me, and to others, young and old, who held him in affection, simply ‘Jayanta’ that he loved and insisted upon to be addressed as.

Speaking of his inimitable meditative poetry qualified by an inner silence and connected to his soil and personal, spiritual, and sensual soul-searching words, I summarize his essences by quoting him, “All the poetry there is in the world appears to rise out of the ashes.” (from: Jayanta Mahapatra a journey)

A poem of his, I loved much, that say in essence his attachment to his soil, its climate, moods, his personal connection to it, its ways of loving and timidity, its unconditional surrender and serendipity:

A HOT MAY AFTERNOON

Not a breath of air anywhere.

Just my sinful sorrows

Keep craving for a kindred being.

Windows are shut tight

In houses everywhere.

And outside, farewell after farewell.

How can I break

This grating silence of the river’s

Burning sands inside of me?

When I muster

Enough courage

And reach for my lover’s breasts,

With a half smile

She hands me the first book

Of an untouched life.

X X X

1969, late forenoon of February. I was standing on the library verandah of Fakir Mohan College, Balasore, with some friends. We were students of final year of BSc. with Physics Honors. We had finished our theoretical classes of the final year but were attending college to finish practical experiments in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology.

Before our eyes a man with a dapper ensemble of dark trouser and white bush shirt but looking down with a brooding demeanor was crossing the front lawn. He had a bunch of books in his hand. I recall, it was the parting days of winter and a balmy spring was across the threshold. In that small intimate town, Balasore, almost everyone knew everyone else. Yet I didn’t know this stranger. ‘Was it because of his silences, gentle manners?’, it bothered me.

A friend pointed out, “He is Jayanta Mahapatra, our new lecturer of Physics. He is a strange man. He reads English poetry all the time, but teaches Physics. Those books in his hand, if I am not wrong, should be books of English poetry.”

It was a strange way of introducing a college teacher, and the tone of my friend oozed disapproval, rather insolence. Others behaved as if they had not heard the comments. I grew curious. He never took any of my physics classes because we had no theoretical classes left. He appeared to be maintaining a silent gentle low profile. He also appeared mild and amiable from his brooding face when he entered the library by my side.

being in physics department’s teaching faculty was like being in news in that small town, so our physics teachers claimed a brighter profile than other teachers and rightly or wrongly they were considered brighter than their peers in the college. Jayanta Sir was ignored by our college and even by our small intimate town like a non-event. I guessed few valued the value of silence.

Those days, I was trying to be an Einstein and some misplaced praise including that of a few college teachers for my insight into physics had, perhaps, made me a bit swollen-headed and thick-skinned to appreciate a physics teacher having a love for English poetry. So, I least bothered to seek this mystery man Jayanta Mahapatra out of the wilderness of the then poor town Balasore, in spite of my curious nature. I forgot him.

I met him face to face for the first time, in a sweating April afternoon (in poet’s language a ‘sultry and sweltering April’) in1986 in his famous residence at Tinkonia Bagicha of Cuttack town. The front of the simple two-storey-bungalow, that stood in the heart of the town, was thickly canopied by the low hanging branches of a huge mango tree, a few clumps of decorative bamboo and strands of giant climber-money-plants, all of which competed for accommodation in the remaining little free space after the big brother Mango tree had its lion’s share. A narrow, paved path joined the iron gate in the compound wall to the door of the house.

The small sitting room, where I sat with the then iconic Indo-English poet Jayanta Mahapatra, was cool under the green marquee created by the plants outdoor. The atmosphere had the air of a modern hermitage. I was meeting him on a very selfish purpose to try and occupy a fringe spectrum of the space belonging to English poetry by Indian poets.

After my MSc, giving up my Einsteinian dreams, I was a revenue officer in IRS of the Revenue Department of Govt. of India. A year before 1986, I was launched into writing poetry in English by an association of Indo English poets, the Poetry Circle, Bombay, a really late starting for a poet. I showed Jayanta Sir my notebook with roughly twenty poems, the better ones in my own opinion from among my efforts at poetry in a year’s time.

Over cool nimbu-pani, or Karanji as called by Delhi Walas, that we sipped together, he looked at my poems with attention. Then without uttering a word if he liked or disliked them, he chose a one-page poem on Mahatma Gandhi, and said, “I will take this for my magazine Chandrabhaga. I advise you to read as many poets as possible, from India and abroad, that would enable you to write good poetry.” With that he stood up and folded his hands in a gesture of ‘You may leave now’ and I left with an ingratiating smile.

Selecting a poem of mine for Chandrabhaga, Jayanta Sir had pushed me up to the top of cloud nine; for publishing in Chandrabhaga would be a feather in the cap of any Indian poet writing in English, such was the magazine’s reputation. Jayanta Mahapatra was the journal’s founder editor.

After my first publication of a poem, my poems got regularly published in Jayanta Sir’s Chandrabhaga and other prestigious literary journals, but the icon of the Indo-English poetry, Jayanta Mahapatra would always say about my poetry, “What do I know of poetry, Prabhanjan? Show your new poems to Nissim, Adil and other established Indo-English poets living near you in Mumbai and seek their opinion.”

Around 1990, he was invited by Bombay University to read his poems, a solo reading. Like me many curious listeners among the audience asked him how, when and with what as inspiration, he wrote his inimitable lovely lines. He had the stock answer, “What do I know of poetry?” I would understand his aloofness much later - he was trying not to create spoilt brats in the charged arena of Indian English poetry of those days where patronized poets with swollen pomposity spent more time in shadowboxing than they spent in creative work, and occupying themselves in forming groups of literati-bullies capturing important platforms by quid pro quo technique of maneuvering.

Then he kept visiting Bombay (that turned into Mumbai around 1995), frequenting the city for his wife’s treatment and we had many meetings while running hospital errands together. We used the opportunity to go around Bombay. He and his wife were foodies and his favorite haunts were places like Sion-Koli Wada’s narrow lanes where fish and prawn fries were mouth-watering at affordable prices for us, the two mavericks without deep pockets, or Sindhi Camp in Chembur where chicken and mutton curries were riots for food lovers and Chowpatty at Girgaon as well as that at Juhu for Pao Bhaji.

We had also frequent visits to Arrey, where a large patch of the prime jungle, an extension of the Western Ghat biodiverse flora, was preserved to serve as the lungs of Bombay, as the Amazonian Rain Forests were maintained as the lungs of our planet Earth. Initially I took him to the well-kept parks like Chhota Kashmir inside the Arrey but he had no liking for either the topiary or other art forms of pruned trees standing in discipline. He loved the naturally and irregularly growing plants and creepers and preserving the secrets of nature in their shaded dark, serenaded by birds, bees, thrush and cicadas.

To describe his down to earth simplicity, I would quote one occasion. During his Bombay stay at his son’s place. Menka Shivdasani, a friend of mine and a well-known poet of Mumbai, one of the founders of Poetry Circle, the haloed association of Bombay Indo-English poets, asked me if I was available to have lunch with the poet Jayanta Mahapatra in her house? I reached her Santacruz flat, my memories might be hazy about the location, and found many young poets hobnobbing there. I missed the lunch for my late arrival.

I looked for the presiding poet and finally found him not reading or discussing poetry with others, but at the kitchen sink giving his hand in washing the dishes. He and a woman poet were doing the dishes. He was like that, a bit Gandhian, always eager to help and accommodate others with a personal touch.

Though we became personally close, we hardly discussed poetry or literature. I never directly knew if he found my poetry of any standard. My wife was very unhappy about the company I kept among the poets and was very critical of my poetry. He found my writing too sensual for her taste. I had a poem on Mira, the Bhakti poet of Mewar royal house. My wife would say, “It’s a pity, you even did not spare Mira.”

I overheard she discussing Mira with Jayanta Sir once when he was having a cup of tea at my place. But Jayanta Sir explained, “He writes very good poetry. Sensuality is a side of Mira’s spiritual songs. Your husband is not wrong. I have observed him developing a new style of his own.” His words behind my back made me as happy as he had made me during our first meeting by selecting my poem on Bapu for Chandrabhaga in 1986.

My moves out of Mumbai on transfer to other Indian cities reduced our person-to-person meetings to almost zero. We would write letters to each other, or talk on telephone. Again, I stress, in all our small talk, poetry was conspicuously absent.

His peregrination reduced because of bad health and age. He was in late seventies when his son passed away and he lost his wife, who had grown close to me also. He had also lost another soul close to his heart, the old and sprawling mango tree in his little garden. The giant fatherly tree was uprooted in 1999 Super Cyclone that devastated Odisha. With the tree he lost as if one of his guardian angels. Then, after a decade and odd years his faithful, lifelong maid-care taker, and emotional support Sarojini passed away.

During my annual visits to Odisha, I would meet him invariably and would see him growing feebler at every meeting. But his mental fitness would amaze me. He had a photographic memory. He would badly miss Mumbai’s Pao-bhaji at Chowpatty and fish fry at Koli Wada. But he never missed the poetry scenario at Mumbai. I felt he considered us, the Mumbai (Bombay) poets, more-gloss, less-gold, more-sound, less-action.

The last we met a few months before he passed away. He was bound to his easy chair mostly. He looked shrunken in body but robust in spirit, his toothless face beamed as beautifully from among the creases and wrinkles.

I recall presenting him a poem I wrote on him when Nani and Sarojini were alive, that he read and beamed. –

SILENCES

We crowded you, your room,

your personal space

by the Mango tree,

like clucking hens, we three

made a commotion of thirty.

And you sat in your bubble

of solitude, silent, wearing

an inscrutable mood

between downcast and detached,

a praying Buddha, with eyes ajar.

You encompassed the silence

of eons, of humans, animals, plants;

living, dead, spiritual, and feral;

on the earth, in sea, and the sky,

visible, sentient and beyond.

After the informal tea, Sarojini,

Nani, and me, the three of us,

making the hubbub of thirty;

Sarojini, Nani and you stood

beneath the iconic Mango tree

The tree was no more physically there

but still existing like the river Saraswati,

a benign myth; resolutely dead

but living indelibly in memory like

an unfinished yawn, an arriving sneeze.

Gone were the tree’s nesting birds

the scurrying ants, but their ghosts

hobnob like the fruitlets that once

lent freshness to the swishing wind.

I joined you three to bask in its aura.

For a change, we fell silent, the infection

from you was catching us up, late

perhaps, like a footnote.

Nani and Sarojini appropriately wearing

their moods, to say 'bye' to me.

But, you, the Buddha, parted your lips,

making me, the poor greedy devil,

to spread my napkin to collect

the crumbs from your lips. But you only said,

"I love the cacophony you bring."

Disclaimer - The above personal reminiscences about the eminent late poet, who is only ‘Sir’ to me and many, are reproduced from memory spanning over 50 years and more, from the late afternoon day in February, 1969, the day I cast my eyes on him. So, everything might not be accurate. But I have been honest in their essence, if not scholarly in inking them. (END)

Prabhanjan K. Mishra is an award-winning Indian poet from India, besides being a story writer, translator, editor, and critic; a former president of Poetry Circle, Bombay (Mumbai), an association of Indo-English poets. He edited POIESIS, the literary magazine of this poets’ association for eight years. His poems have been widely published, his own works and translation from the works of other poets. He has published three books of his poems and his poems have appeared in twenty anthologies in India and abroad.

Sreekumar Ezhuththaani

The room was cold, the AC humming faintly in the background, yet I felt sweat bead on my forehead and trickle down my temples. The irony wasn’t lost on me—the room designated for senior doctors, where comfort was promised, had become a suffocating cell. My eyes drifted to the photograph of Mahatma Gandhi on the opposite wall, the inscription beneath it glowing faintly in the sterile light: Satyameva Jayate. Truth alone triumphs.

But what truth? Whose truth?

His face swam before my eyes—the real estate agent. His trembling hands. The hollow in his eyes as he received his son’s body after the post-mortem. A face ravaged by time and something darker. A line from Hamlet floated to me unbidden, reverberating in my mind: Who was he to me, or me to him?

It wasn’t the first time I’d seen him, though I doubt he recognized me now. Years ago, in a distant town, I had seen him on his knees, his pride shattered like porcelain under a boot. "Doctor, please," he had begged, his voice hoarse and his hands clasped as if in prayer. His breath reeked of despair. "You must help me. I’ll lose everything—my life, my son, my name."

He had killed his younger sister in a fit of rage, a single, monstrous kick that sent her into oblivion. When he found her lifeless body, panic had taken hold. He’d hung her from the ceiling fan to simulate a suicide. It was a crude tableau, and he needed me to write the final stroke of the forgery—a false post-mortem report.

I hesitated then, wrestled with myself. But in the end, his wealth spoke louder than my scruples. An apartment in the city sealed the deal. The truth, or whatever semblance of it remained, was buried with his sister. His young son had accompanied him that day, a wide-eyed boy clutching a toy car. His innocence was a silent rebuke, one I buried as easily as the truth.

Years rolled by like slow, grinding wheels. When I was transferred to this remote hill station hospital three days ago, I thought fate was finally giving me a reprieve—a place to disappear into quiet obscurity. But fate has a twisted sense of humor.

The boy, now a man, had drowned in a pool notorious for its treacherous depths. He had come here alone, celebrating his success in some national exam. The water claimed him in silence. His father, now stooped and grayed, had to cross half the country to retrieve what was left of him.

I watched the man as he sat in the corner of the mortuary, clutching his son’s belongings—a damp wallet, a soaked certificate, and that same toy car, now rusted. He didn’t cry. His grief was a vacuum, pulling all sound from the room.

"Doctor," he croaked when he saw me, his voice faint and brittle. "Is it true? Was it quick?"

I didn’t have the heart—or the cruelty—to tell him that the autopsy suggested otherwise. "Yes," I lied. "It was quick. He wouldn’t have suffered."

He nodded slowly, the words falling on him like a benediction. "Thank you," he whispered, his gaze lowering to the toy car in his hands.

I walked back to the office, my legs heavy, my mind cluttered. The photograph of Gandhi stared at me again, unblinking, unyielding. The words beneath it burned into my thoughts: Satyameva Jayate. But what did truth matter when lives had already been shattered, twisted into something unrecognizable?

The AC continued its low, mechanical hum. Outside, the mist curled through the hills like ghostly fingers. I closed my eyes and leaned back, feeling the weight of years, of choices, of truths I could no longer run from.

I rang up my family just to make sure they were safe.

Sreekumar Ezhuththaani

I stood for a while in front of the a wide open piece of land surrounded by low walls. No doubt about it—this was the place. But apart from a couple of nosy neighbours and a few tired faces peeking over the back wall, there wasn’t much activity. A line from G. Sankara Kurup’s poem "Today Me, Tomorrow You" popped into my mind:

"No festival of flowers, only the rhythm of despair;

No showering of flowers, only tears of the child in grief."

Before I could shake off the unease brought on by the scrutinising, sneering eyes of the new tea maker I had to put up with in roadside tea shop, this piece of land and an old shed in it appeared on my way back. The sun was about to rise and the shed could be hardly seen.

It had all started a couple of months ago. Some of us at the office decided to make a short film. The idea came from a real life incident. A young man had been working as a sweeper at our office—a guy with an almost feminine grace. Watching him sweep and mop, you’d think he loved the job so much he’d do it even without pay.

But soon, he lost the job. The position was reserved for women, and his name—Baby—had initially misled everyone. The day he was left, he cried his heart out, and the office felt like a house of mourning. None of us even felt like having lunch that day.

Someone remarked that if he’d lied and claimed to be a woman, he could have kept the job. That sparked the idea: what if someone actually did that? There was a story there. Hari Prasad with no delay wrote it down for our company’s monthly newsletter, and when Aravind, our computer operator read it, he said, “Let’s make it into a movie.”

The set? Our office itself. The actors? Us. The only problem was casting the role of Baby. We tried finding him, thinking he should play himself, but he’d gone somewhere in the high ranges looking for work.

That’s when Satyan dragged me into it. Jokingly, he said, “You’re barely five feet tall—you’d be perfect for Baby’s role.” Everyone took the joke seriously, and I had no choice but to agree.

I’ve always been nervous on stage. How was I supposed to act in front of a camera? Thankfully, the film didn’t have too many dialogues. It was titled "Muted Wails of Thulsi."

But there was another problem—my gait. Five years of NCC parades in college, plus some inherited mannerisms, meant I had a very stiff, masculine way of walking. My strides were firm, inward, and balanced by a slightly stiffened neck and swinging arms—hardly suited for the role.

That’s when Sobha Devi from accounts stepped in. She was also a part-time dance teacher and taught me how to walk differently. She drew curving lines on the floor and showed me how to soften my movements. Sudhakaran Sir joked that Mary Lincoln had trained Abraham Lincoln the same way.

But learning wasn’t enough—I had to make it natural. So, I came up with a solution. I started taking early morning walks, practicing a more delicate, tentative stride. If anyone saw me tiptoeing around like that, I don’t know what they’d think.

And that’s why, as I stood outside those walls, mustering my courage to be seen like this.

I had found a way out of this—one that served a dual purpose. Not only would it help me perfect my role, but it would also let me amaze everyone in front of the camera. I had to shine in my role, no doubt about it. No one had ever even jokingly said I had a feminine side. So, what was there to hesitate about?

Every morning, I started dressing up as Tulasi (different from how Baby looked), my character from the short film, and went out for a walk. After a couple of days, the regulars along the path stopped noticing me, as if I’d become part of the scenery. Yet, some odd incidents did occur.

The first was when I bumped into a woman one morning. Had I been in my usual male attire, I might’ve gotten scolded—or worse, slapped—for grabbing her arm as I stumbled.

Another unexpected benefit was how I quit smoking. The urgency to light a cigarette didn’t align with my new routine, and over time, I stopped entirely. That alone saved me more than two thousand rupees.

One day, Sobha Devi, who had shown me how to mince my steps, casually remarked, “Something seems different about your stride.” Thankfully, no one else seemed to notice.

At five in the morning, there’s a tea stall that opens nearby. A fat Tamilian minds the counter and a lean and hungry looking Bengali youth makes tea. He started calling me “Ladies” with exaggerated respect. Whenever I went there, he’d find a way to stand close to me and serve my tea with extra care. Even if the place was crowded, I was served first. While others got their glasses slammed onto the granite table with a loud clatter, he handed mine over gently.

Once, I accidentally left my umbrella there. He came running after me, shouting “Ladies!” and handed it back with a shy grin.

This morning, though, he wasn’t at the tea stall. When I asked the owner about him, I learned his mother had passed away. He lived just across the road from the stall in a shed used to store construction materials for a building under construction.

Something compelled me to visit his house. I used to dread attending rituals and ceremonies, but this time, I felt no hesitation. Perhaps because I knew there wouldn’t be a crowd, I didn’t even go home to change. If I went like in shirt and pants, he might not recognize me—this was the only way he’d ever seen me.

I walked through the open gate and stepped inside. In the middle of the shed lay his mother’s body, draped in a tattered cloth.

Death doesn’t discriminate—it commands respect, no matter where or whom it touches. I went closer, bent down, and touched her feet as a mark of reverence.

The boy, who was sitting on the floor sobbing, looked up at me with tear-filled eyes. Then, suddenly, he stood up, came forward, and hugged me, crying uncontrollably. Through his wails, I could hear him, “Deedee, Deedee.”

As I held him close to my pounding heart, a few tears fell on my wrist. I wasn’t sure whose they were—his or mine—but I instinctively wiped my eyes.

Sreekumar Ezhuththaani known more as SK, writes in English and Malayalam. He also translates into both languages and works as a facilitator at L' ecole Chempaka International, a school in Trivandrum, Kerala.

Ishwar Pati

The Bay of Bengal has been host to a series of the dreaded weather system—the cyclone. Cyclones roar and recede. But not so the storms generated at home with my wife. In fact, if all of them were harnessed in a tea cup, they would make Cyclone Fani look like a tea party. The hot air of one partner rides over the cold air of the other to unleash wind speeds approaching infinity! To the lay observer the war-like situation at my home may appear amusing, but does he have any idea of the criticality of the issues at stake?

What are the issues that invariably draw us out with our daggers drawn? A major one is the manner of making the bed in the morning. We start the day with a tug of war over the bed sheet and the bed cover. When I try to spread the bed cover over the crumpled bed sheet, she rips it away in frenzy. “Don’t you have any common sense?” she screams. “You have to shake and ‘air’ the bed sheet before covering it with the bed cover!” I leave the bed sheet shaken but not stirred! My argument, that both the bed sheet and the bed cover will have to be ventilated anyhow before we go to bed, has her eyes rolling and her tongue tied.

Another time is when she issues clear instructions not to disturb her in the kitchen no matter who comes. “I don’t like to meet anyone in the ‘state of my dress’,” she explains. I agree with her totally as I shoo away a few ‘unimportant’ visitors. After they have gone and the work in the kitchen is over, I casually mention their names. Suddenly she is at my throat! Why did I not tell her when Mr. B had come? Her ‘clear’ instructions apply to Mr. A and C, not to B! She doesn’t mind meeting him with her dress in a mess because he is like a family member! I can sense a storm brewing as she picks up velocity, “I had to talk to him about the servant he had promised to bring. You don’t know about that, do you? How could you? You are not bothered even if I die from overwork, as long as you get your meals on time!”

I feel it prudent to ride out the gale rather than join issues with her. Cyclones pass, but storms in a tea cup hound me like a dog chasing its tail.

Ishwar Pati - After completing his M.A. in Economics from Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, standing First Class First with record marks, he moved into a career in the State Bank of India in 1971. For more than 37 years he served the Bank at various places, including at London, before retiring as Dy General Manager in 2008. Although his first story appeared in Imprint in 1976, his literary contribution has mainly been to newspapers like The Times of India, The Statesman and The New Indian Express as ‘middles’ since 2001. He says he gets a glow of satisfaction when his articles make the readers smile or move them to tears.

Sujata Dash

I am in my twenties.

Not married till now.

Never married rather.

I had some flirtation though.

Those small misadventures cannot be termed as affairs.

I think everyone has some such experience or the other.

A few openly admit. Some cherish these moments quietly.

I met this guy in a gathering the other day.

His roving eyes made me feel uncomfortable and embarrassed. But , let me confess ...I enjoyed the kind of attention I received , being my maiden experience so far.

Does this happen to all of us?

Are we all attention seekers?

I kept on prodding my cranium and received a deep silence as the answer.

I gave credence to the silence as an affirmation and went with it.

The gentleman I met , was roughly in

his late forties.

He was suave , tall , fair and attractive. The mustache he wore ,sat perfectly well on his sharp featured demeanor .

His mischievous and bewitching smile had some magic in it. It made me look back at him in the crowd, more than once and our eyes met.

My initial impulse was to brush him off at the outset, but I was held back by the flattery he had held in his eyes.

In fact I was floored by his gestures.

It was like waking up to a new reality. Till now I did not know that, I savored adulation to this extent.

"So persuasive he was...Omg! His silence too spoke loud and conveyed."

He gave a jerk to my apprehensions as he spoke gently.

" Sorry to bother you miss. I saw you in the gathering. I am new to the city. It seems you are well versed with the place unlike me. I could make out from the way you get along with folks."

" Please don't mind miss when I say you are quite attractive, especially your eyes. I mean it. Well, can we know more about each other?"

" The coffee shop is a few furlong away. Would you please accompany me?"

My curt reply..." I just had coffee " did not deter him from persuasions.

" Well, may be an hour later. Till such time we will chat on random topics. Come along please."

I didn't budge an inch even.

" A few hours later may be."- He proposed.

" I shall wait for you miss at the shop."

There was something more to his persuasiveness.

His words surreptitiously struck a tender chord and I was at a loss for words. Should I meet him ? Or, should not I? It was tough for me to decide.

The story does not end here.

My urge to meet took the better of my meek dispositions and initial resistance took nosedive.

From " I am not sure " to "Maybe " ....it was seamless transition, without any conscious attempt.

Applying some face cream , brushing neatly manicured hair and adjusting my skirt belt to look slim , I headed to the place he had referred to.

As I pushed the glass door if the cafe, I could immediately notice him seated in a corner occupying a small table.

A table for two , leaving no scope therein for any more encumbrance.

Did he do it intentionally to grab my attention or is it his way of doing things as such!

It was a subject for me to ponder.But, I did not go much deep into it.

He was biting nails when our eyes met. He immediately refrained from the offensive act and waved at me , signaling his presence.

I crossed a few tables to reach there. My whole life, I can never forget the warmth that he held in his eyes as he pulled the chair for me to sit.

"Awww! So suave and gentlemanly and such act of chivalry!"- I thought.

"Must be very romantic ."- my wild guess surmised.

He lived in another city. Today, he was there as per his professional commitments. More so, he was part of the gathering as per dictates of his boss. "The boss is always right, needs to be obeyed as such".

The saying goes.

His boss was holidaying elsewhere and had entrusted Aman to attend the so-called family function.

He prolonged his talks. But, I would not say ...

" He was talkative."

Rather he was someone , who mesmerises you with his manners, depth of knowledge and baritone voice. I enjoyed his company.

I know ...I am partial. Let me be.

Crowd at the coffee shop started thinning as evening advanced. At one point of time, It was just the two of us.

We had lingered the conversation sipping our cuppa nice and slow. The snacks he had ordered remained redundant as we munched, gorged on , devoured and gulped down the endearing whiles . Time became memory and we were engulfed in its momentary surge.

The story does not end here.

For, we met several times thereafter.

I knew this much- he lived in another city.

I never enquired the details and he did not elaborate.

But, we met off and on. Especially, when he had to meet some professional commitments in the city. Also, whenever he felt like meeting me.

It was a strange kind of a bond. Neither of us was demanding.

If you are taking it as " None of us was serious about it"

Then probably, you are not wrong.

He would often initiate the talk . I was besotted by the way he spoke and enjoyed the advances thoroughly.Let me not be shy and lie.

I was desperate when he did not contact. At the same time was bemused when he rang. I didn't mind if he called me at the middle of the night knowing well I will not get a wink of sleep even thereafter.

There was something strange, magical yet inexplicable about this feeling.

Some call it "love"

Some " Infatuation" ..

To some other "It is just a dalliance."

He had a family to support. His spouse had a good job. They had two children .

I came know all these details when he showed me the happily married family picture only recently.

Just after showing me the family picture, he confessed about "lack of love" and " marital discord."

I was not a bit emotional as I have listened to such testaments before.

Men need some plea or the other to validate their sorry state of affairs always! He too was trying to do the same.

I was happy that , he appeared brutally honest in his presentations. He acted really well.

A few weeks later he called on me to spring a surprise. Believe me, I was not at all surprised.I could hazard a guess of the move.

We drove to the sea shore ...for I suggested to watch the swell and the surge. He agreed at once.

The foaming sea always fills my heart with love and serenity. He brought the wine bottle and two glasses from his car. He poured some for me. We raised our glasses looking deeply at each other. We didn't utter a word even as our gazes spoke.

He muttered something...

" How subtle is the splendor of the sea! Wish We could spend more time on the beach. The sea entices both with its roars and calmness. Divine and magnificent, Is not it !"

I could read his lips and nodded.

He was about to pour more to his glass and he did , then sipped courting my unkempt mane swaying in the breeze.

I just shook my head when he offered to fill my glass , signaling " This is enough for me. Let's get back ."

He raised his thumb in affirmation and we drove back. We exchanged glances but did not utter a word.

I went to my residence. He headed for his hotel after planting the parting kiss on my cheeks.

But it was not " Goodbye " for lifetime.

May be, I have grown tall, brave , free and wild. Still some element of love and dream exists, I feel.

Another Sunday today. The effulgent glow of the sunset has painted the sky in hues of orange and pink.

Sitting in the balcony, enjoying the quiet summer evening ,my mood of contemplation tips off that-

"My longings have started growing from the cracks of broken heart and dreams."

I don't know ...If Aman feels the same way today!!!

But, one thing is for sure that- " I will not call him, nor send him any message."

Sujata Dash is a poet from Bhubaneswar, Odisha. She is a retired banker.She has four published poetry anthologies(More than Mere-a bunch of poems, Riot of hues and Eternal Rhythm and Humming Serenades -all by Authorspress, New Delhi) to her credit.She is a singer,avid lover of nature. She regularly contributes to anthologies worldwide.

Snehaprava Das

Rishi entered the room eleven days after they had carried her away from there. Everything looked neat and carefully looked after. His mother always liked things to be kept in their appropriate places. There was not a single crease on the bedspread. The pillow covers too looked washed and perfectly fitted to the pillows.

His sister perhaps had kept the room in its right shape. The wooden idol of Lord Jagannath that stood on the top of the closet did not have a speck of dust on it. The mirror fitted to the door of the closet too was dusted and polished. The TV set, the writing table and the large book case filled with many books of English and Hindi and Odia which his mother had either bought and collected ...everything looked neat. The assortments of decorative pieces on the shelves looked the same as they used to look years ago.

Rishi looked at his father who lay

on the armchair, looking sightlessly at the roof. His father who loved to talk and snapped at mother at the smallest slip had suddenly become mute. The tastefully furnished room sagged under the load of a strange silence.

A blue cylindrical object lying at one edge of the top of the closet caught his eyes. Curious, he pulled it out carefully. An umbrella, that was perhaps bright blue once but now had gone patchy and faded, was kept neatly folded in its plastic cover.

He remembered the umbrella. It was the same one his mother used to carry in her handbag while going to office. She held it over his and his sister's head while they walked to the the school which was some three hundred meters away from their home. During those days children did not go to school in the school bus or in their parents' car or on the bike of the father, like they do now. They mostly walked to the school.The umbrella served a double purpose. It protected him and his sister from rain when it rained and from the heat of the sun too. Mother never let them walk without the protective shade of the blue umbrella. The umbrella, like his mother always held its caring drape stretched over her children, anxious to keep all the trouble at bay.

He had forgotten the umbrella after leaving school. He studied higher secondary for two years in a local college and then left his hometown. Later he went out of state for doing a specialized course. Life had been so rushed that he did not find time to communicate much with his mother. Most of his conversations were with his father. His sister too got married in the meantime. Somehow, he shrank inside as he confessed to himself, he had begun to feel indifferent towards his mother, as if he had lost the need of her in his life. Father continued to snub mother as ineffectual and incompetent as he had been doing all through out drowning mother's feeble protests with his loud counter arguements. Rishi and his sister too had now realized that their mother knew nothing much about outside world.

A laconic, self-contained person, mother never tried to defend herself or explain things to the children whom she had given birth and reared up with utmost care.

She did not dress in the way sophisticated ladies did. She wore her hair in a long braid, did not apply make up to her face. Rishi could not remember a day when mother had clad herself in an expensive sari or did her hair in modern fashion. All put together, his mother to Rishi, was an outdated woman who loved to live in the past. The glamour of the institute where he did his specialized course had gone into his head. Whenever her mother wanted to pay a visit to the hostel, Rishi stopped her on several pretexts.

He remembered the convocation ceremony. Almost all the students had invited their parents. But Rishi had shied away from the thought. Father could have come but he was afraid that if father mentioned the convocation ceremony mother might want to accompany him

So he did not let them know about the ceremony. Later, mother had learnt about it from one of her colleagues whose son also studied in the same institute. 'Have you not told aunty about the convocation ceremony?'

His friend asked. 'Why do you ask that?'

'She said she did not know about the function when my mother asked her why she didn't come,' his friend said.

'I told her. She might have forgotten it. You know she keeps so busy ...'

Rishi was preparing excuses to justify his fault as he travelled home in the holidays that followed the function.

But mother never mentioned it. She got busy in preparing the dishes he loved and taking all care to see that he spent his days at home in comfort and happiness. The day on which he returned to the institute his mother got up early in the morning, did the puja and made breakfast for him. She had packed snacks and sweets in plastic jars for him. For a brief moment as he bid goodbye he looked into his mother's eyes. There was something in them he could not describe but which made him feel guilty. It appeared as if she strove to push back words that were about to escape her defying all her resistance.

Thereafter whenever he met his mother he found her strangely quiet..She never made him feel that she was trying to distant herself from him but he could sense it and felt ill at ease in her presence. He got a job and was posted in another city. Mother came and arranged things in his new house. Both father and mother stayed there for a few days and left. He too got married after a couple of years. Mother loved Sheila, his wife and cared for her in the same way she did for him.

Though not obvious but the distance between them some how increased after his marriage. Mother and father came to live with them after his son was born. They were very happy and spent most of their time with their grandson. Since he and his wife worked in a multinational company and had to leave home around eight in the morning mother had to take care of the household responsibilities. She had to look after the baby too which in itself was a full time job. Sometimes he felt guilty to burden his parents especially his mother with these responsibilities at this age but he too had no alternative. May be mothers are, as his father often commented, are taken for granted people.

If she felt overworked or weary mother never complained. She appeared to be really enjoying herself in the company of her grandson. However his wife was not too happy about the way mother cooked traditional dishes of his choice. Like all women she also had her dreams of cooking new items for her husband. But she had no choice too.She had to depend on her parents-in-law for the safety and proper rearing up of her child. But she was dissatisfied with the whole arrangement. Rishi realized that his wife disliked her mother-in-law's extra involvement in certain matters, especially her interest in cooking special dishes for her son and the rearing up of the baby. Mother liked to feed the baby the food which she used to feed her own children. But his wife was in favor of following the nutrionist's diet plan for the baby. Though she never expressed it Rishi could understand his wife's unspoken resentment. He also understood that it was his duty to keep his wife happy. He recollected how he had adopted an apparently discrete way for doing so.

'I have made coconut cutlets, your favorite', mother said, coming out of the kitchen. 'Taste this one...' she put one cutlet on the plate. Rishi and his wife were eating a quick breakfast. His wife cast a glance of disapproval at Rishi. Rishi picked up the cutlet and kept it aside on another plate. 'Pack them in my lunch box mother, ' he said, 'we will eat it during lunchtime.'

'I have packed them for both of you in your respective lunch boxes. This one is just for tasting..'

'We are getting late,' Rishi cut in. 'There is no time for tasting it. We will eat it with our lunch', he said and got up.

He knew he sounded rude but he had no choice. 'Mother would forget it. She never minds my words,' he thought to himself and left for the office.

He couldn't detect any sign of accusation on mother's face when he and his wife returned in the evening. Mother and father were playing and laughing with his son and looked happy. But, Rishi could now recollect, mother had thereafter never urged him to eat any of her specialties. She would cook and serve but never ask to eat more as she had been doing. Every thing seemed to have become very formal. He had not taken note of it at that time. The memory of one after another such incidents like this, which he had not cared to take seriously then, came flooding back, drowning him in a deep sense of regret. After his son started going to school, mother and father returned to their hometown. A year or so after Rishi and his wife left India to settle abroad.

His father, who was used to touring places while he was in office, found it difficult to spend long hours at home. And he took his frustration and boredom out on mother. Mother too had retired but her retirement was not taken seriously as her doing a job. Rishi and his wife mostly communed with father. Mother only wanted to ensure that they were all happy and in good health.

She hardly discussed anything beyond that.

Perhaps, Rishi tried to reason now, father would have cut her short or snapped at her if she tried to prolong her conversation with her son.

Rishi could not remember any occasion since his childhood when his mother had countered his father. That might be the reason why he and his sister had got to ignore their mother's advice and suggestions, and believed her to be thoroughly incompetent and useless as other family members did. Even after all these years it was father who dominated the conversation.

Now as he stood holding the umbrella neatly packed in its plastic cover he realized why the woman who had spread out herself like an awning of love and protection over them became cocooned inside a closed world. She had ungrudgingly folded herself and squeezed into the cover of her self-rejection.

Rishi took the umbrella out of its cover and opened it. He held it over his head for a while and then folded it. He ran his hand over the cloth that had gathered the patina of time over it and then put it back inside its cover.

His wife was doing the packing. They would be leaving the next day. His sister would stay for some more time with father and make the necessary arrangements.

'What is this?' His wife asked, holding out the blue umbrella. 'Why have you put it here in this suitcase?'

'I will take it,' Rishi said grimly, 'pack it along with my clothings'.

'But...' His wife tried to say something but held her words back.

'I will take my mother with me ... she has always tried to keep me close to her but has always been cruelly defeated. From now on she will always be with me.' Rishi promises to himself as he wiped his eyes

Dr.Snehaprava Das, former Associate Professor of English, is an acclaimed translator of Odisha. She has translated a number of Odia texts, both classic and contemporary into English. Among the early writings she had rendered in English, worth mentioning are FakirMohan Senapati's novel Prayaschitta (The Penance) and his long poem Utkala Bhramanam, which is believed to be a.poetic journey through Odisha's cultural space(A Tour through Odisha). As a translator Dr.Das is inclined to explore the different possibilities the act of translating involves, while rendering texts of Odia in to English.Besides being a translator Dr.Das is also a poet and a story teller and has five anthologies of English poems to her credit. Her recently published title Night of the Snake (a collection of English stories) where she has shifted her focus from the broader spectrum of social realities to the inner conscious of the protagonist, has been well received by the readers. Her poems display her effort to transport the individual suffering to a heightened plane of the universal.

Dr. Snehaprava Das has received the Prabashi Bhasha Sahitya Sammana award The Intellect (New Delhi), The Jivanananda Das Translation award (The Antonym, Kolkata), and The FakirMohan Sahitya parishad award(Odisha) for her translation.

Bidhu K Mohanti

A student is in between different addresses. I got down at the railway platform of Cuttack Station, and placed the steel trunk and bed holder on the ground. It was a hot and humid mid-day on 22 May 1976.I had left behind the hostel life in the small town of Berhampur. A short tricycle rickshaw ride, on way assisting the rickshaw puller on an uphill stretch, took me to reach the parental house. Here, the address changed. I had passed the MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) and completed the mandatory one-year internship. A day later, on 24 May 1976, a permanent medical license was given to me by the state medical council without a whimper. The medical profession took a journey outside Odisha, yet I have held unto this registration for all these years.

50th Year, Wow! Without a preamble, the batchmates in an indolent way have exchanged, “Come 2025, we will plan to celebrate our 50th year of pass out in 1975 from MKCG Medical College”. WhatsApp has become the go to rendezvous platform. There is no disbelief for me. Yet, counting the years give a sense of weight. In our own small ways, each of my batchmates alongside thousands of other doctors, nurses and health workers have never shirked to work for the ‘health of the nation’. As a cancer specialist, I have seen the success of cancer cure and the dread of cancer failure. She had looked vacantly into my eyes, “When would the bleeding stop? I can not anymore bear the pain”. I have had by own share of mental uncertainties and sleepless nights. And then, lo and behold, six months later she returned for a follow-up and demanded to be noticed, “Look at me, is this yellow saree nice on me?” Her disease had responded well to the treatments and she was tumor-free. In our journey through the medical profession, there are always those moments when you could make a patient happy with himself or herself. She left an irresistible sprinkling of joy within that out-patient corridor on her out of the hospital.

‘Wow’ is unlike most other words in English language. The three letters are spoken with various facial expressions by millions daily all over the world. Its origin is traced to Scottish verbal exchanges in the early 16th century and has taken nearly five centuries for its infectious spread across all spoken languages globally. An interjection or expression of amazement and excitement toward the others in your company, “the pathology teacher wowed us all by a demonstration of human tissue sectioning through a rotary microtome”. In a world captivated by such ‘wow’ moments, the humanity has struggled to understand the body-disease-mind connection. Fifty years in the practice of medicine is such a small fragment of the medical history. In the last decade or so, I often sit through all the opinions and information the patients and their family caregivers have gathered through social media and informal well-wishers before they would reach me. Often, I would not hesitate, “Wow! Your knowledge about your uncle’s mouth cancer and its possible treatment course is superb. I can’t add anything more”. Nearly a decade after the cancer diagnosis and its treatment in 2015, my cancer has recurred leaving the colleagues who treated me earlier to re-understand the disease course.

In our eighth decade, there is an upbeat chaos around the 50th year pass out Reunion. Who knows, the old age adrenaline rush would make them wildly sing, “Chal chal re naujawan”-the cheeky duet sung by Mohammed Rafi and Asha Bhonsle.

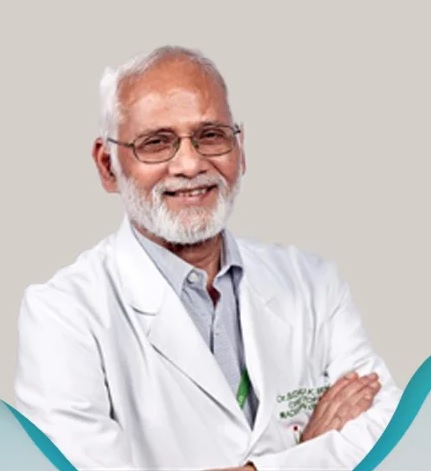

Dr. Bidhu K Mohanti, is an oncologist, former Professor at A.I.I.M.S., Delhi and is presently the Director-Academic, Bagchi Sri Shankara Cancer Centre & Research Institute, Bhubaneswar 752054, India. He occasionally writes non-medical pieces in popular medium. Email: drbkmohanti@gmail.com

Anita Panda

Eight months have passed to come to Delhi leaving Kithor Rural . This is my first experience to reside away from birth place. Often it comes to my mind that a Govt job in a small place was much better than this city life. To serve those innocent and needy people was providing utmost satisfaction. To compete with the rat race is beyond my scope as I find here people are self centered and running after money only.

My husband, with commercial temperament, a nonmedical person , born and brought up in a metropolician city . I wonder, would he ever understand the value of serving the needy folk. Ever since we were married he rebucked me for the choice of my life. My parents were also acknowledging my husband and motivating me to go to Delhi for a happy married life. My Husband would say; “ Half of your life journey is already over, although it is difficult to accept the change either at work place or home, but in due course of time, one adopts. So far you have learned only about that Kithor Rural, Sadulpur, Sakarpur, Surajpur etc .Thank God, since in that rural areas there was no medical school, so you got the opportunity to go to Meerut for MBBS degree. Although in study you have spent much, struggled hard, but not shown to the world your brilliancy. Though you worked for others, what have you got for yourself! Now it is the right time to progress golden; open a clinic at Delhi, earn well and enjoy.

I argued ; “ I know Delhi does not value a plain MBBS. I will forget what all I had learned in my Medical School. “

He would answer back; “No doubt, you will remember what you have learned. Besides you will earn money, stay with your loving husband and above all will learn about the culture of city life.”

Though I am not accustomed to argument, but asked to myself, “ City Life ! Here people are selfish to the extent that they forget even their parents if that suits them.”

He opened a grand clinic for me. But, as I was oriented to selfless service even in private practice I kept my consultation fee very nominal against the will of my husband. Perhaps due to my social and friendly dealing , efficiency and more importantly low fees, I was getting many patients for consultation every day.

One day I was getting ready for clinic, the phone rang. Before I picked up the phone, my husband read the name and sarcastically said to me; “Wish you all the best! Enjoy your whole day with the mad lady.” He further continued putting his hands on receiver and speaker; “This woman is totally psycho. Her demands are turning the whole family mad; she complains she is neglected all the time.”

I resented the comment about my patient but kept quiet. I was uncertain if my answer will just speak about my rural background social knowledge as I was ignorant about the tradition of urban family.

However, the word ‘ psycho ‘ provoked me to know more about the patient’s background. Mrs Samiksha Mathur,60 years is the wife of a rich personality who remains busy with other women but no time for his own wife! Son works in a corporate.

Mrs Mathur was told by some doctor years ago that she is suffering from a serious brain disease for which she needs regular follow up, but none of the family members was serious about it. Also because of her old age she was neglected otherwise. Therefore, she used to visit Doctor’s chamber alone always.

Somehow I was not convinced. If the brain disease is a serious one how come it is not progressing for last so many years and she appears very healthy! I examined and investigated her thoroughly and found out that she has a minor ailment ‘Focal Epilepsy’. But I questioned myself “Knowing it is a serious disease how come the family’s attitude is casual ! May be this is the City Life. However, I must teach them a lesson. But how ?”

Next morning I called Mrs Mathur and asked her to keep the phone speaker on. Then I said; “ you need an urgent brain surgery Mrs Mathur. If it will be done now it may cost 2-3 lakhs. So deposit one lakh tomorow as advance at hospital. Also I want to discuss the seriousness of the disease and surgery with your children .”

I could over heard her discussion with some family members. “We have planned to go for outing, so it can be done only at a later date, not tomorrow.” Once she was back to the phone I continued, look Madam, you are not understanding the seriousness of the disease. If not done urgently it may spread to the other organ of the body . Not only then it will cost more but it may be life threatening also.” Someone perhaps kept the hands on mouthpiece and mouth piece of the phone, so I was unable to hear their discussion. After sometime ,“ Madam , it is about my life, I don’t want to die;” Mrs Mathur spoke in a chocked voice. Again I could hear; “ Don’t be so fussy , on my way I will deosit the money, but no way I can cancel my trip. Disgusting.” After disconnecting the phone I called the father of Rahul , a child ,for MRI same time as I gave to Mrs Mathur.

Next morning , reaching in clinic I asked the attendant to send both the patients to the chamber simultaneously. While examining Rahul, I had an eye over Mrs Mathur’s two accompanying persons ( I guessed they are her son and daughter inlaw) who repeatedly were looking their watch. Then I said to Rahul’s father; “ Mr Jain, you mentioned earlier that both of you are jobless and today is your interview . You can go and appear the interview. If at least one person will be selected that will be an asset for you all .The Test can be done some other day.” Both parents exclaimed together; “ No Doctor, Rahul’s health is much more important than the job.”

“Did you hear Rahul? For your health, your parents are sacrificing their carrier. But once you will grow up you would not have time for them.” Then I consoled Rahuls parents that this is not brain surgery that if not done immediately it will affect other organs and may be fatal. You can bring him tomorrow.

After they left,I called Mrs Mathur and started in a howling voice ; “ Today also you have come alone. But without family members consent the surgeon’s hands are tied. I am sorry, you go back, when your children can spare some time for you, then come.” I left the chamber.

Evening, I got a phone call from Mrs Mathur’s son; “ I am sorry doctor, you have taught me a very relevant point. Please give me an appointment, I will bring my mother for surgery. ”

I was smiling to myself. Neither the surgery is needed for Focal Epilepsy, nor I am a neuro surgeon, simply a MBBS Doctor. This was just a plan to provide some lesson to the children who don’t understand the value of the parents.

Repeatedly it was coming to my mind, To ignore the parents in old age, to send them to Elderly Care, now became a trend in urban population . Within no time it will spread to rural area also.

We often comment, the modern children are bad. They don’t understand parent’s value. Yes, it may be partly correct as the trend is to follow the modern culture. But this is the parents who had not taught their children about right and wrong. Parents are the first GURU for the them, so they blindly follow the parents . Of course in due course of time they adopt whatever suits them. I remember a phrase;“when you blame and criticize others, you are avoiding some truth about yourself.”

So the moral of the story is “Rather than commenting the children are bad, it is the duty for all of us to solve the upcoming issues, we parents have to show the children the right path.”

I am sure, we can change their attitude. “ Rome was not builted in a Day “. “The sea is formed with the accumulation of water drops only.”

Dr A. Panda Professor of Ophthalmology Dr Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences All India Institute of Medical Sciences,New Delhi, India Fax-oo91-11-26588919 Tel: 0091-11-26593177

Minati Rath

Reading of what happened recently with Saif Ali Khan brought back memories of something I went through ... an anecdote which is a very pivotal experience in my life which I want to share with all.

23rd November, 2009, a date that I will always remember. This was close to the time we had gone to attend the shraadh ceremony of my father and had just returned back to Rourkela. Both children were studying outside of the city at that time and it was only the two of us - my husband and I. Those who have ever been to Rourkela Steel Plant would remember, the houses are typically very large with huge gardens, servant quarters a little farther out, surrounded by lots of big bushes and fruit trees. This meant the space between neighbours could be quite high. Winter evenings tended to look dark due to fog and streetlights could sometimes be not adequate to light up the place.

There used to be a black dog that always made itself comfortable on the front porch but that particular night of 23rd November he wasn't there. It was raining outside and I had just come to the back of the kitchen to close the doors and windows when I heard a noise coming from the drawing room. I thought it was some routine noise and went out to see what was happening. Typically, at that time Dr Rath, my husband, would always be in the drawing room so I wasn't very alarmed. But what I saw when I entered the room would forever remain etched in my memory. Two people, covered from head to toe in some black garment, with masks on their face, had entered the house. One of them was holding a knife to the neck of Dr Rath.

Startled at seeing me enter the room, the other man ran towards me brandishing the same kind of knife. I was so shocked that without thinking I caught hold of the knife in my hand. I grasped it so tightly that it cut my hand slightly, with some amount of blood coming out through my elbow. He released my hand and asked me to sit down. His companion kept holding my husband’s neck with a knife glued to it and made him sit down next to me. They asked us for the locker keys. Unfortunately, the almirah was open with the key hanging on the almirah itself.

At that moment all I could think of was a similar incident that had happened two years back in Rourkela where a retired GM & his wife were killed at their home by robbers. My heart was pounding, thinking of that situation. I was thirsty and requested for water and at knife point he took me to the kitchen to have some. Bringing me back to my seat they tied us both to our chairs and proceeded into the house to raid the almirah. I still remember they took everything out ……all the ornaments ..…gold and silver, not even leaving behind the junk jewellery. Mobiles, cameras, purse with personal documents - they left nothing. Having ransacked the house they closed the door and vanished.

It took us a little time to struggle out of our chairs and then we rushed to call out at the servant quarters and dialled a call to the police. They responded immediately and sent men in uniforms to guard the house through the night. Investigation was started on war footing, and both the culprits were soon arrested. Funnily enough, they were identified through the drops of my blood on the knife and were eventually caught by Rourkela police while sleeping in the railway station. We will always be grateful to the police department of Rourkela for their swift action. We were deeply thankful to all the well-wishers, neighbours and friends who stood by us with their unwavering support and kindness.

Support from Delhi police was timely and valuable. Without their prompt action to expedite the recovery of the stolen property, we would not have received back every single thing that we had assumed we would never see again. When we were called to the police station we met the two miscreants. Seeing them without masks and in a civil dress, we realised they seemed just like normal people. We were not sure what compels people to act like the way they did.

When I think back on those harrowing moments, staring at what we thought was sure death, the disarray in the house reminding us of all we had been through, I shudder. But what I realised is that not losing one 's head in such situations is the most important thing that we can do. While I am eternally grateful to God for sparing us that evening, the trauma of the incident is secondary to the fact that having the right people around can get you through anything. Our calmness in the face of this life-threatening danger was probably what got us through while panicking would surely have been fatal. All I can say is that I will always remember this but would always be thankful to God for getting us through it. People get out and about in the neighbourhood. Kids play together, neighbours head out of town on vacation, people visit, and inhabitants tend to their yards. The wonderful thing about neighbourhoods is that they support a sense of community, and a sense of community means safety. But, in order to make your neighbourhood safe, everyone must come together. Every child deserves a safe and healthy childhood and a place where he or she can play without worries. That’s why it is important that we help each other build a safe neighbourhood where kids, neighbours, and friends feel secure.

While a perfectly safe neighbourhood is a tough ask, it’s a challenge that each of us can do something about. In many ways, some steps can make it easier to protect our homes, neighbourhood, and community, and ensure we come together to live safely.

1. Know Your Neighbours - Always get to know your neighbours. Don’t just meet them but really try to get to know them. Communication is a big factor in safety.

2. Enhance Your Home’s Security - Always keep your doors locked and keep spare keys with a trusted neighbour or family member instead of under the doormat or near your home. Invest in a home security system, a doorbell camera, or a combination video/alarm system. Doors and windows with alarms are a crime deterrent and cameras allow you to capture any mischief in real-time. Not only can you see who is on your property, but you can also typically watch for anything that doesn’t seem right within a couple of hundred feet of your home.

3. Make it Less Appealing to Steal - Keep your doors, windows closed at night so thieves can’t see your belongings, such as a big-screen TV, appliances, or other technological gadgets. Also, keep your windows closed when you’re out during the day and at night.

4. Don’t Announce When You’re Away on Social Media - You’re telling criminals just what they need to know to get in and out while you’re not at home. This also puts your neighbours at risk.

5. Get to Know Your Local Police Officials - Get to know your local police officials and express to them your desire to make your neighbourhood safe. Put Neighbourhood Safety First and Everyone Wins. Improving neighbourhood safety is a team effort, but it needs to start with someone. As you get to know your neighbours, discuss your concerns, and apply some of the ideas above. You’ll find that your neighbourhood becomes not only a safer place to live but a more enjoyable one for everybody.

Minati Rath is a member of the Krishnamurty Followers' Group and an active paricipant in the group discussions. She is also a social worker. A regular reader of LV and other literary journals, she lives in Hyderabad with her husband who is a retired doctor from SAIL.

LIFE LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE NEWSROOM

Deepika Sahu

The year 2025 marks the 30th year of my professional journey as a journalist. Journalism as a profession has undergone massive transformation in the last three decades. News is now at the click of one’s finger. Whatsapp forwards are now unfortunately being termed as news. We are living in strange times amid an overdose of information, fake news and issues of ethics plaguing the media. It's not easy to be a journalist in today's time. But then for a journalist, it's almost impossible to resist an authentic story and the urge to let it travel through the world. A lot of people perceive journalism as a glamorous profession. However, not many are aware of the grime, the sweat and not to talk about long working hours with erratic shifts and very few holidays. But it is definitely one profession that gives you an ability, a perspective to look at even your own life like an outsider. It’s intoxicating to be in the newsroom day after day, week after week and actually year after year. The joy of finding the story and holding the story within you and then letting it travel to the world is unexplainable. Once you let it go, you have no control over it. And it's that juxtaposition of brutality and tenderness that has fascinated me all these years. The brutality of telling a story as it is and the tenderness of the story becoming a part of my inner life is truly joyful. I believe, if you don't have it in you to come face to face with death, violence, loss and grief then you can't be a journalist. You got to be somewhere else.

The newsroom has been my shrine for years and I have learnt many lessons from the newsroom. I am sharing a few of these lessons here.

Every day is a new beginning: What will be the big story at the end of the day? On most days, journalists start their day on this note and we navigate through the day as per its destiny. I still distinctly remember the evening of November 12, 1996. The editor-in-chief of India’s leading news agency (my workplace then) was having a conversation on the perils of having a dull news day and we were all discussing what would be the next day's headline. And exactly after 30 minutes, we got a panic call in the newsroom. And then came the horrible news of the mid-air collision at Charkhi Dadri which killed 349 people on board. We all worked at the office till the wee hours.

Time and events unfold before our eyes and being in the newsroom gives us an intoxicating feeling. We can’t bask in the glory of bringing out an error-free edition which has already been a part of history or an already published wonderful story/article, headline or very well-designed page. We have to take each day as it comes. Every day’s performance comes under scrutiny. We embrace each day as a new beginning and we learn and unlearn from each day’s work.

Life lies in details: A wonderfully written story in a newspaper will lose its charm even if there's a small spelling mistake. Newsrooms have taught me the importance of the power of detailing. A wrong caption can kill a mesmerising picture. Some years back, I did an interview with a leading theatre personality and director. My editor praised me for a 'well-written interview' and I went home feeling happy that night. The next morning, I woke up to horror. The reason: the desk person did not pay attention while doing a spell-check in the copy I had written. And the theatre personality's name Rita Mafei was published as Rita Mafia. And to top it all, she was an Italian (So 'Mafia' became more deadly in this case). I wanted to go underground that day. However, Rita was gracious enough to say, “Even prominent international newspapers have made similar mistakes.” And she had a hearty laugh too. But there is a life lesson to it – Pay attention to even the smallest details.

The beauty of life lies in its interdependence: Like life, a newsroom is all about interdependence. It is like a game of cricket or soccer. The newsroom is not only about reporters, sub-editors or editors. The newsroom is about working very closely with photographers, graphic designers, illustrators and tech support teams. So, it’s all about interdependence and interconnectedness. In a newsroom no one can work and thrive in isolation. The newsroom is also a wonderful space for reverse mentoring. I have learnt a lot from my younger colleagues and those lessons have made my life rich and textured. Same goes in life too. If we are open and attentive then we can learn from our young sons, daughters, nieces and grandchildren. The beauty of life lies in acknowledging our interdependence. The basic philosophy that holds true is : “I am there because of you.”

Life is full of possibilities: As journalists, we never in our wildest dreams ever thought that we could bring out a newspaper sitting in our homes. The COVID-19 pandemic threw all our earlier life and professional experiences into the wind. As we worked from our homes (from different locations), we collaborated with each other and brought out the newspapers as per our daily strict deadline. It was a journey which was intense, deeply exhausting and full of challenges but it also taught us the most important lesson that life is full of possibilities. We learnt that human beings have an innate ability to push boundaries under challenging circumstances.

There's no greater virtue than credibility and compassion: You can't be a good journalist if you lack credibility and the virtues of compassion. If you are a journalist then you should be able to talk about anything to anybody with dignity and compassion. A good journalist needs to be a mindful communicator which means having a sense of empathy and compassion. Being credible means those around you will trust you. The same goes for life. If one wants to live a fulfilling life then one needs to have credibility apart from being compassionate and non-judgemental. The newsroom teaches us to say no to stereotypes and to be sensitive to community, gender and differently abled. We can live better when we become inclusive and open.

Be in sync with change: When I first started my career in 1995, we had no idea that one day the internet would be so overwhelming in its presence. It has changed the way we read, write or gather news. The times have changed. Today, we look at both print, videos, web stories and social media posts as part of our profession. So, the lesson is – always be open to embrace change.

Look beyond the tag: I often remember that 'nameless' person (from a small place in Haryana) who made a phone call to the PTI office in New Delhi to tell us about the mid-air collision. He kept on saying, "saab maine dekha...maine dekha (I saw it, I saw it)." For a journalist, every source is sacred. The newsroom teaches us to be open to having conversation with people from diverse backgrounds. The same goes for life. The lesson is not to live in your cocooned world. Take a step forward and talk to people around you. Get out of your comfort zone – the newsroom mantra has immense value in life too.

Knowledge is power: The world might say anything but knowledge is powerful. Senior colleagues of mine read five to seven newspapers in a day apart from books on different subjects. Everyday they add something to their knowledge universe. There is no limit to knowledge. At the same time, the newsroom also has taught me that there is a difference between information and knowledge. To flourish in life, one has to be a seeker of knowledge not an information chaser.

The story is the ultimate hero not the story-teller: A journalist tells the story but he/she is not the story. It's the story that is much much larger than any journalist. It's the story that matters, not the story-teller. A journalist is just the narrator bringing the story to the world. People bare their vulnerable souls in front of journalists and share with them their own intimate stories of love, loss, success, failure, vulnerabilities and aspirations. The problem starts when the story-teller thinks that he/she is the story. The narrator can't be the story and he/she has to draw the boundary of telling the story and separating the self.

This is probably best explained by Sebastian D Souza (who worked in Mumbai Mirror), famous all over the world for his photograph of Kasab in action in CST (Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) station in the 2008 Mumbai terror attack, which eventually led to Kasab's conviction. My close friend, who worked with Sebastian, asked him once, "Sebastian, didn't you feel scared while you were clicking photographs of Kasab?" He said nonchalantly, "What was there to feel scared? I was just doing my job -- shooting Kasab with my camera. That’s it." He didn't glorify his moment of truth, how brave he was or how he put his life into risk.

The same works in life too. We have to remember that the world is much bigger than us. Everything in this world need not revolve around us. This lesson becomes more precious now as we are living in an age of social media with an inflated sense of self.

Even as I reflect upon these life lessons, I also feel that we are all stories in progress.

Deepika Sahu is an Ahmedabad-based senior journalist with a career spanning since 1995. During her career, she has worked with India's premier media organisations, including the Press Trust of India (PTI) in New Delhi, Deccan Herald in Bengaluru, and The Times of India in Ahmedabad. Currently, she is contributing India-centric features to Melbourne-based The Indian Sun, a cutting edge media platform. In addition to her journalism career, Deepika is involved in teaching English and Communication Skills to learners from different parts of India through Manzil, a Delhi-based NGO. Beyond her professional endeavors, Deepika is passionate about India's rich diversity, literature, blogging, quiet hours at a cafe and enjoying a cup of tea.

Shri Satish Pashine

Priya Mehta’s life unfolded in the sun-drenched streets of Jaipur, where the aroma of freshly fried pakoras wafted through the narrow alleys, mingling with the heady scent of marigolds during the festival season. Jaipur, with its vibrant colours, bustling bazaars, and echoing temple bells, was a city that thrived on tradition and community. Yet, the lively chaos of its streets was a stark contrast to the quieter storms brewing within Priya’s heart.