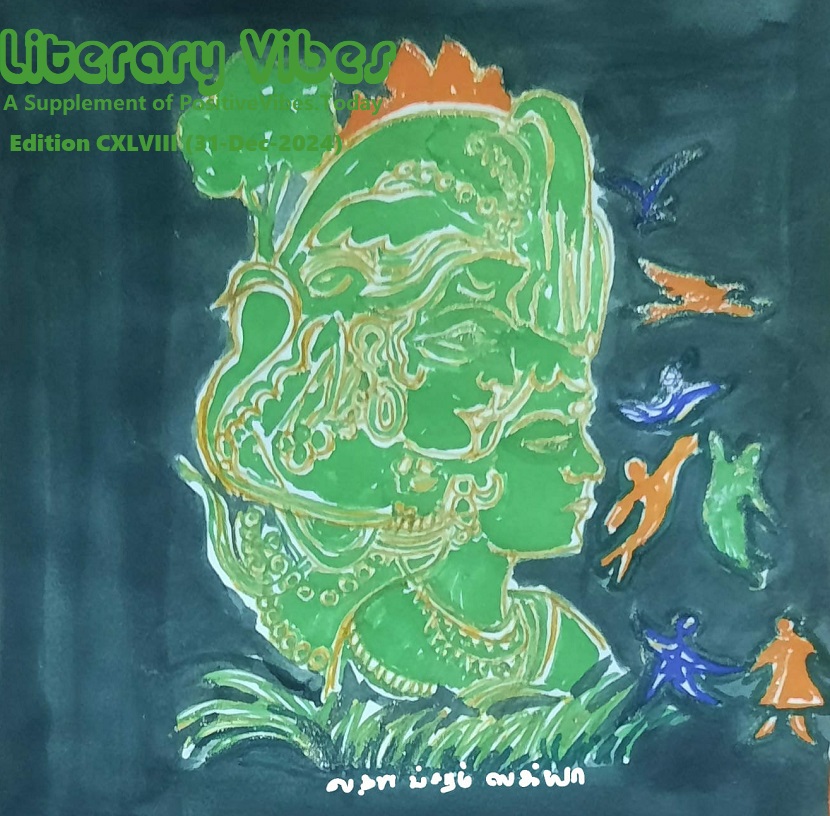

Literary Vibes - Edition CXLVIII (31-Dec-2024) - SHORT STORIES & ANECDOTES

Title : Gods and Humans (Picture courtesy Ms. Latha Prem Sakya)

Prof. Latha Prem Sakya a poet, painter and a retired Professor of English, has published three books of poetry. MEMORY RAIN (2008), NATURE AT MY DOOR STEP (2011) - an experimental blend, of poems, reflections and paintings ,VERNAL STROKE (2015 ) a collection of all her poems. Her poems were published in journals like IJPCL, Quest, and in e magazines like Indian Rumination, Spark, Muse India, Enchanting Verses international, Spill words etc. She has been anthologized in Roots and Wings (2011), Ripples of Peace ( 2018), Complexion Based Discrimination ( 2018), Tranquil Muse (2018) and The Current (2019). She is member of various poetic groups like Poetry Chain, India poetry Circle and Aksharasthree - The Literary woman, World Peace and Harmony)

Table of Contents :: SHORT STORIES & ANECDOTES

01) Sreekumar Ezhuththaani

ANOTHER

02) Prabhanjan K Mishra

SCENT OF A SAGA

03) Ishwar Pati

THE LOST RUPEE

THE CANAL

04) Krupasagar sahoo

THE GYPSY GIRL

05) Satish Pashine

MUMBAI: THE CITY OF DREAMS

06) Snehaprava Das

OF ALL THE LOVE IN THE PORTRAITS

07) Shafeek Musthafa

AGAIN ON A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT?

08) Dr. R. Unnikrishnan

NEW YEAR—THE CYCLE OF RESOLUTIONS AND SOLUTIONS:

09) Manjula Asthana Mahanti

A MAN OF RARE IMAGINATION

10) Dr. Rajamouly Katta

THE RAINBOW

11) T V Sreekumar

SWARNACHITRA

12) Bankim Chandra Tola

MAN AND ANIMAL

13) Gourang Charan Roul

HARBINGER OF MULTICULTURALISM: DIWALI AND HALLOWEEN

14) Soumen Roy

SOCIAL MEDIA TRIAL

15) Sreechandra Banerjee

A LETTER TO MR SANTA CLAUS

RHAPSODY OF RHYTHMS

16) Nitish Nivedan Barik

A LEAF FROM HISTORY: AN INDIAN WOMAN LEADER AND THE INTERNATIONAL DAY!

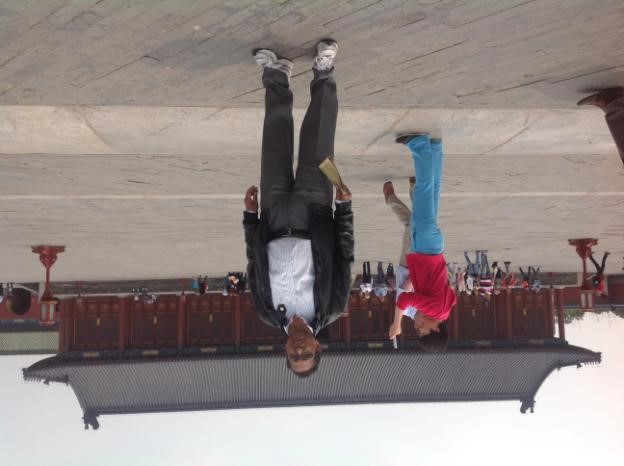

17) Mrutyunjay Sarangi

THE EAGLE

When I heard about Harish’s death, I instinctively felt it was a suicide. I didn’t need to wait for the post-mortem report to confirm it.

Since his wedding, I had never seen Harish genuinely happy. Ask him anything, and all you'd get was a dismissive, "It’s fine. Just going on."

It was Harish’s father-in-law who first brought the matter to my attention. He approached me one day, looking uncomfortable.

“You should talk to Harish,” he said. “Advise him on how to handle things.”

“What things?” I asked. “What’s going on?”

His response was vague. I couldn’t make much of it, but something about his tone bothered me. The next day, I decided to speak to Harish directly.

At first, he was reluctant. After some prodding, he opened up a little. His married life, he said, had become monotonous. The main issue, according to him, was Hima’s demeanour.

“We just… don’t get along,” he said, avoiding my eyes.

“Can I talk to her?” I asked cautiously.

He hesitated but eventually nodded. “You can try. Though, honestly, I don’t think it’ll help.”

Harish and I went back a long way. I had taught him for a few years, and over time, we had developed a strong mentor-friend relationship. The fact that he, of all people, felt hopeless made me uneasy.

I insisted they see a marriage counsellor. “There’s a friend of mine, John,” I suggested. “He’s good. Maybe I can tag along to help smooth things out.”

Two months later, Harish and Hima, along with Hima’s parents, met John. Despite professional boundaries, John filled me in on the details afterward.

“Your guy, Harish, is just like you,” John said with a chuckle. “Workaholic. Busy round the clock. Meanwhile, Hima stays at home, looking after his aging mother. He barely sees her for one meal a day.”

“What about Hima?” I asked. “Did she open up?”

“Not really,” John admitted. “She’s not the talking type. Her parents did most of the talking. They’re sweet people, though. They even gave Harish advice right in front of me.”

“Advice? Like what?”

“Stuff like, ‘Son, you should spend more time with her. Don’t let work take over your life. Come home early, take her out, maybe sit and chat.’ You know, the usual.”

“Did you agree with them?” I asked.

John hesitated. “Look, they weren’t wrong, but something felt off. Anyway, I told Harish to try. Told Hima a few things too. Let’s see what happens in a couple of months.”

A month later, Harish came to see me again. He looked worse—exhausted and defeated.

“How are things now?” I asked.

“They’ve gone from bad to worse,” he admitted bitterly.

“What happened?”

“Hima’s parents keep coming over to advise me. It’s endless,” he said, mimicking them. “‘You need to understand her, son. Sorry, she’s been pampered all her life. She loves you; she just doesn’t know how to show it. Why are you working so hard? For whom? What’s the point of earning if there’s no peace at home?’”

He sighed. “I did everything they said, sir. I cut back on work, spent more time at home, even planned little outings for her. For a few days, it felt like a second honeymoon. But she didn’t soften. If anything, she became more distant.”

I didn’t have much to say to that. Frustrated, I called John to discuss the situation. The conversation quickly turned into an argument.

“Counselling doesn’t work miracles,” John said bluntly. “Behaviour might change a bit, but deep-seated nature? That rarely changes. People think love can fix everything, but that’s just a fantasy. It’s a lie we tell ourselves.”

A week before his death, Harish came to see me again. This time, he handed me an envelope.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“My passwords,” he said. “I keep misplacing them. Thought I’d write them down and leave them with you.”

“Good idea,” I said. “I should give you mine too. Who knows, I might kick the bucket before you.”

He didn’t laugh. “Don’t say that, sir. I can’t imagine you gone.”

As he left, he hummed a line from N. N. Kakkad’s poem: ‘When, where, and how—who knows?’ I had an odd feeling it was the last time I’d see him.

After his death, I found more than just passwords in that envelope. It was, in a way, a key to his mind. Harish had sacrificed so much for Hima, prioritizing her over his own mother. But his efforts had only deepened his despair when nothing changed.

Hima’s parents knew she was difficult. Even Hima might have sensed it on some level. But the human mind is a strange thing—it likes toy play fatal games.Haris h’s love for her, instead of bridging the gap, worsened her behaviour. Her mind, perhaps unconsciously, took his affection as a reward for her irritating nature and bad manners. It dawned upon me that this is what commonly happens. The sacrifice from one and the craving for more of it from the spouse.

At his funeral, Hima’s cries were heart-wrenching, but I couldn’t feel sympathy. They seemed less like the mourning of a lover and more like the panic of someone who had lost control.

Death isn’t the only enemy.

Sreekumar Ezhuththaani, known more as SK, writes in English and Malayalam. He also translates into both languages and works as a facilitator at L' ecole Chempaka International, a school in Trivandrum, Kerala.

1.Nakphodi

Sundar’s office room was being cleaned, vacuumed, anti-pest treated, and pruned of junk files and articles. Sundar for the time being sat elsewhere. Two staff members brought to him a very old trunk for scrutiny. After rummaging into its contents, he found a long-lost old leather pouch. The rest were returned for junking.

He recalled the leather pouch from a time, a little less than two decades ago. He clasped it now to his chest as if he had got back a lost treasure. It reopened floodgates of memory, and brought tears to his eyes. His mature lady secretary, perhaps noticed her boss going emotional, so, left the room on the pretext of some work, leaving him to cry in privacy.

The leather case contained a bright red bridal sari of the finest Banarasi silk. He gingerly felt it against his cheeks and deeply inhaled into it like searching for a lost love, a lost glory, a bonhomie; an intimate aroma. It was wrapped over her grandma for a few hours during her last journey and before going to the pyre.

. Sundar recalled how he had rummaged among two mounds of old and used textile items heaped together by his bua, Subhadra Devi, the stern elder sister of his father. The items were to be ritually given away to the family’s washer-woman, being the used clothes of a dead person, considered ritually unclean. Sundar had finally found granny’s red sari and secreted it away in that leather pouch. In a house, turned upside down by the great tragedy, he forgot where he had stashed away the pouch.

Sundar would recall, away at Bombay (later renamed Mumbai), he had received a telephone call from his father one morning, with a scary message, “Your grandma has been missing for two hours, along with her day-and-night-companion Nakphodi. We are searching for them.”

Grandma, during one of her rare visits of her parental village, had found an orphan girl of around five years. The kid had been roaming, homeless. She had no name, except being called – ‘Hey you!’ During her toddler years, grandma learnt, the kid lost her parents and close relatives to dreaded cholera. The toddler then survived on uncertain meals and sleeping space provided by villagers. Sundar’s grandma took a liking to the kid, and brought her home as her grand daughter.

The five-year old kid had a minute hole on the left side of her left nostril’s lobe, a birth defect, just as Sundar’s grandma had, that she hid behind a diamond nose-stud in her youth, but now left bare. The little hole convinced grandma that girl had a blood line with her.

Sundar who just had celebrated his tenth birthday, wrinkled a naughty nose at the hole on the girl’s nostril, and teased ‘Nakphodi’ meaning, ‘A girl with a hole in the nose’. Surprisingly his tease struck a chord in grandma’s heart and stuck to the kid as her nick name. Everyone addressed her as Nakphodi, thereafter.

Nakphodi ate and played with other little kids of the family but slept with grandma. Before Nakphodi, Sundar used to sleep with grandma but he had stopped because his peers teased it as a sissy-habit. Grandma was growing lonelier in bed, haunted by her stark and prolonged widowhood. Nakphodi moved in to the empty space vacated by Sundar and returned grandma’s affection with lots of kiddish love, that came naturally to a love-starved five-year old.

Nakphodi, grew as the apple of grandma’s eyes, and Sundar’s pet, but other kids became jealous of her because she had apparently stolen their portion of grandma’s love also. Nakphodi was put to the village school as Sharvari Pandit, proudly flaunting the family title ‘Pandit’. She was a fast learner and would excel over kids of her age in the school, later in college also.

In two years in grandma’s house, Nakphodi left her dollhouse-days behind, though other kids of her age continued playing with their dolls and toys; and she came to kitchen to give a helping hand to Sundar’s docile mother in cooking the joint family’s multi-tier meals – breakfast, lunch, evening snacks, and dinner, with umpteen cups of tea throughout the day.

Nakphodi quickly learnt to prepare the special snacks and meals for the grandma, keeping with her advanced years, and delicate digestion. That was a real relief to Sundar’s mother. Knowing that Nakphodi had prepared her meals, grandma relished her food with extra satisfaction, eating a few spoons more during her frugal meals, which gladdened Sundar and his parents. They loved Nakphodi all the more.

Soon Sundar had to move away to cities for higher studies and then joining his government job at twenty-one. He visited his village only during festivities and holidays. Nakphodi, studying in their village junior college, growing fuller and lovelier, would pleasantly surprise him during his visits, but it pained him to see grandma growing feebler.

Sundar could not make head or tail of father’s message over phone that morning about his missing grandma, but panicked. How did a person in her eighty-fifth year with a seventeen-year-old girl, Nakphodi, studying in junior college go missing in a quiet village, everyone almost knowing everyone else’s whereabouts all the time?

He rushed home by flight within hours, with his heart in his mouth. After alighting from aircraft, he took a taxi to his village. When his taxi was passing over the little river behind his house, he inhaled a whiff of the approaching spring. The air was laced with the smell of ripening paddy in surrounding fields at that hour of the sundown. His worried mind however refused to dwell on the lovely aroma.

When he reached his house, he found it crowded with neighbors. He entered gingerly on tiptoe. On a veranda by the second inner courtyard of their sprawling multi-tiered mud house, in the fading pink light of the setting sun turning the fronds of coconut palms golden, he found his grandma lying on a white bed. Holding his breath, he approached her, and found her in death’s pallor.

Some villagers were hanging a translucent canopy-mosquito-net over her to keep away the bothersome houseflies. Her mortal remains lay wrapped in her bright-red bridal Banarasi silk sari, Sundar remembered it as one of her prized possessions from her own marriage days. She was also bedecked with gold and diamond ornaments. She dazzled like a bride. That was her last wish when she spent almost five decades of widowhood wearing only white saris and a string of Rudraksh beads.

Sundar broke down by grandma. When he rose from his immediate sorrow, his teary eyes searched for his parents and Nakphodi. His father rose from grandma’s other side, a stumbling ghost, looking like a cyclone-devastated tree, broken at the waist.

There were no tears in his eyes, only a rising frost. He saw his father’s feet dragging themselves behind him like deadwood, his hands lifeless in their pallor and his voice, a defeated raw whisper. He was the youngest of grandma’s brood and her pet son among her five living children.

His father rasped in a low voice, “At eight o clock in the morning today, your mother informed me, 'Mother and Nakphodi have not come down, check if they are alright?' A discreet check found both missing from their room and were nowhere in the neighbourhood. A passerby from village asked me, ‘Why Nakphodi is searching something in the river water by the bathing ghat all by herself?’ That unnerved me and I ran there with a few neighbours.”

His father’s narrative moved fast. The search party found Nakphodi in the water, searching for something frantically. When asked about grandma, she pointed into the water. She looked dazed. Grandma was nowhere. What Sundar’s father gathered from the panicked girl’s incoherent talk, the previous evening after her early dinner, grandma had wished for a dip in the river like many of her secret excursions in the company of Nakphodi.

Apparently, grandma soaked herself in the shallow cool water near the bathing ghat on the riverbank, asking Nakphodi to sit on the dry earthen highground and wait. Nakphodi while watching grandma in shallow water, dozed off. When she woke up, the day was breaking, the night had passed apparently. She could not see grandma anywhere. She panicked and fainted. When she regained consciousness, she started searching for her in the water.

A search for grandma started downstream. The water was chest high at its deepest. The current was very mild. But it appeared overpowering for an old and frail woman pushing her eighties if she was caught in its grip. Grandma was found by around twelve-thirty, a mile downstream from where Nakphodi sat, floating face down like a big dead fish among the reeds, weeds, and rushes by the river-edge. The village doctor made a guess that she might have died in water the previous evening.

Father and Sundar grieved together. Their tears mingled, and hours, days and ages seemed flowing down their cheeks. They had lost their last mooring, Sundar’s father his mother, and Sundar his grandmother.

Sundar enquired about Nakphodi, and his father informed that after fishing out grandma’s corpse when villagers went to bring Nakphodi home, they found her searching for grandma in the river’s water in a frenzy muttering incoherently. She did not listen to villagers that grandma had been found and taken home, but continued her search in the river. Village doctor said, she was suffering from an anxiety seizure.

She had to be taken home forcibly and the doctor gave her a sedative injection. She was sleeping in grandma’s room heavily sedated. Sundar’s million-dollar questions had to wait for Nakphodi, the last person to have witnessed grandma alive.

The time came for grandma to be readied for the pyre. The bridal attire and ornaments were replaced with her religion-sanctioned-attire of a widow: a white saree and a Rudraksha string. Sundar found his bua making heaps of grandma’s used clothes and other textile articles to be donated ritually. From there he smuggled grandma’s bridal sari, just taken off her body, and secreted it away. Late night, he lighted grandma’s pyre most lovingly like igniting a holy fire.

Next day saw a new bad development. Again, Nakphodi had a seizure attack. She ran and jumped into the river and started searching for grandma with a frenzy. That time it came to light, except Sundar and his parents, none in the family liked Nakphodi. After the old relative’s death, for which they held Nakphodi’s carelessness to be squarely responsible, they ganged up to throw her out, the orphan girl, from the house. Sundar had to stand his ground and did not leave Nakphodi’s side for a minute. He feared worse harm from his uncles, aunties and cousins for Nakphodi.

Though Nakphodi’s seizures became less frequent and shorter in duration and less intense as days passed, but grandma’s death and the hatred of household members made her depressed and traumatic. She lived like a shadow of her earlier jolly-self.

Sundar could not increase the burden of her mother by leaving behind Nakphodi in her traumatic state. So, he decided to take her along with him while returning to his job. But his parents and villagers looked bewildered. How could it be socially allowed? So, Sundar expressed his willingness to marry the orphan girl and take her to Mumbai as his wife. Sundar’s father organized a simple marriage and dispatched Sundar and Nakphodi to Mumbai as husband and wife.

2 - Grandma

Sundar would often trace back his family’s history by listening to, and piecing together the bits and ends of what he heard, from the mouths of his grandma, parents, uncles, relatives, old servants, and neighbours.

His grandma, Soudamini Devi, meaning lightning, had come as a young wife of fourteen years of age into his grandpa’s life. She was not less naughty and swift than her namesake, lightning. Grandpa was a rich young landlord, and had recently taken the reins of his responsibilities as the Zamindar into his hands after the death of his father. Grandpa was all of fifteen years.

India was ruled by the British those days as one of the colonies of their British empire, headed by King George V. The rich and high-caste Indians, like Sundar’s grandpa, had fallen into the trap of the ‘Divide and Rule’ policy of the colonizers, and saw the British as their savior and mentor in retaining power over the ordinary people.

With the style of an administrator and the zeal of a missionary, Sundar’s grandma, the new bride of the household, ruled her home territory. She was a domineering little woman with a strong will. She ruled her nuptial bed like its queen.

The British monarch ruled the British empire on which the sun was said never to set. As an antithesis, grandma did not allow the sun to rise in her empire, her bedroom, where she remained twenty-four hours a day ensconced with grandpa, with all blinds drawn for many days after her nuptials, such was her and her husband’s passion for each other. Their family members and servants said they did not know what was happening behind the blinds, except grandma’s telltale giggles now and then.

In the years that followed, the virile couple bred like a pair of lemmings, eleven pregnancies in twenty years flat, a full co-sexual cricket team. Of them five survived, four boys and a girl who was older to all of them, Sundar’s present Subhadra bua and the youngest of the brood was Sundar’s father. Had Sundar’s grandparents’ virile project gone unabated, it could deliver further teams of football, Kabaddi, etc., but unfortunately his grandpa died young at the age of thirty-five only.

It was a rising and rousing period for India under the British Rule, stirred by freedom call of M. K. Gandhi, a Gujarati Bar-at-Law (Barrister) done at London, who had served a successful stint as the counsel to a rich Indian firm at Durban in South Africa, had returned to India, his native soil. He was the apple of the eye of Indian freedom-lovers, adored as ‘Bapu’, who had brought the mantra, Satyagraha, a fight to finish for one’s rights but following truth and non-violence. He prodded the Indians to claim freedom and self-rule as their birth right from the British colonial rulers.

Barrister Gandhi before returning to India had worked as a social reformer and activist fighting in Africa for the rights of the Indian diaspora, mostly Indian migrant workers, with the power that be, and was successful in many issues with his formula called Satyagraha, the passive resistance.

Gandhi ji after arriving in India was making waves in minds of most awakened Indians, reaching to even the remotest villages and the most sleepy-Indian minds, as well as quite a few among the British-boot-licking zamindars, native princes, Rai Bahadurs, etc.

Gandhi ji, besides political freedom, fought for social freedom by encouraging female education, giving up untouchability and hatred for the so-called low-caste or low-born people, etc.

Sundar’s grandparents at that juncture of time, however, rejected this secular, vegetarian Gandhi, and his views of renouncing untouchability and giving education to the girlchild. They were brainwashed to think of Gandhi as an ungodly heretic. They totally disliked Bapu’s call for a secular and casteless India, also his call for freeing India with Satyagraha. They disliked Gandhiji’s call to use only Indian products in spite of their raw quality, and reject the refined articles of British make.

They rejected Gandhi in favour of another theorist of freedom. The guy was Vinayak Savarkar, a Maharashtrian, who envisioned a free Hindu Rashtra to be carved out of the British-ruled Indian Peninsula with the help of the British Rulers, and receive it as a friendly legacy.

One night Grandpa died in grandma’s arms. To the best of Sundar’s guess from grandma’s various hints, ramblings, and monologues, his grandpa had died during coitus, as his weak heart did not sustain the extreme excitement, resulting in a massive cardiac arrest.

A hazy sepia photograph, mottled with spots of greying and dark patches showed a vain young man suppressing a smile as if taking his life as a joke. It was Sundar’s only link to and memory of his grandma’s mysterious husband, his grandpa who died young.

Grandma brought up her children well, educating the boys in the best schools and colleges available. But keeping alive her dislike for Gandhi’s call for female education, she taught her only daughter, Subhadra, the oldest of her surviving brood, up to rudimentary reading and writing at home with the help of a tutor, and got her married when she was a pubescent child of thirteen.

But the pubescent girl, Subhadra, whom Sundar addressed as bua, became a widow shortly after her marriage and was sent back to her mother by her in-laws; considered unlucky and inauspicious for their family. Sundar’s grandma was adjusting her life to her own recent widowhood, when her young daughter returned home as a grumbling child-widow. She reeled under the deluge of those misfortunes. But she rose like the proverbial Phoenix from the ashes of her tragedies.

She established her control over the family as a young dowager and matriarch. Her impartiality and care as the family head, earned her the love, respect, obedience, and fear of all family members.

But Sundar’s family tenderly accepted grandma’s weakness for her youngest son, Sundar’s father, who stayed with her all through the thick and thin of life, managing the vast landed property. Her other three sons, Sundar’s uncles, had fallen in love, married, and brought home highly educated wives to grandma’s great dismay, defeating her objection to female education. The three sons had jobs in cities and lived there, their wives visiting the village off and on.

But her big and last bastion, rejecting Mahatma’s call to reject untouchability and abominable hatred of low-castes, fell next in a dramatic way. Her eldest grandchild, a college going girl, eloped with her lover-classmate. To add insult to her injury, it came to her knowledge that the lover-boy belonged to a caste of untouchables, who were liquor-brewers and leather-artisans.

The day, the bad news was delivered (of course, Sundar at five was too young to understand the impact, but he would learn it later), grandma received the news with exemplary calm, her family interpreting the calm as that before a storm. The worst detonation was feared any moment. As if to ignite the detonator, Sundar’s father, a young follower of Gandhi ji behind his mother’s eyes, giggled non-stop.

But the other name of Sundar’s grandma was ‘Surprise’. She did a few somersaults in her arena of principles, and her much-feared explosion turned into a smile. With a beatific smile grandma ordered, “Call those elopers, the gang of loafers and rascals; let’s roll out our red carpets for their welcome our prodigal children into our family.” Her humorous mood made her family uncomfortable and nervous. But Sundar’s father continued giggling, as if more privy to his mother’s reality than others.

Pulling a long face with an expression of disbelief and dismay, she burst out, “Haven’t you, my bloody ignoramus flock, read or heard of the ‘The parable of the Prodigal Son’ of Jesus from the holy Bible?” No, they had not read or heard. It was not less than a bomb blast of knowledge.

Hurt and angered, the family heads of Sundar’s village gathered in grandma’s courtyard that evening for raising their voices against her decision of welcoming a Scheduled caste boy as her grand-son-in-law into the Brahmin fold. But the grand lady roared like a tigress, “You fools, you blind believers, followers of outlived shibboleths, don’t you sense the change of wind, see the societal weathercocks?”

The only protest her family heard was from a feeble old man, “What is a weathercock, Soudamini Devi?” Grandma waved away his feeble ignoramus detractor like a bothersome fly on her nose.

She changed strategy, smiled crookedly, and quietly reasoned, “Please read great thinkers like Marx, Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, or your own native philosopher Gandhi. Don’t be born-deaf and blind, die-deaf and blind cases. Read these authors to know that females are equal to males, all humans are equal across the casts and creeds, and God is one. Read Darwin to know that unless you marry far and wide across castes, creeds, and races, your progeny would be physically and mentally weak.”

Her family, anticipating the downfall of the female autocrat that evening, was wonderstruck to see the village elders eating ladoos (sweets) from her hand, extending ‘congratulations’, taking packets of ladoos for their families, and leaving one by one.

3 - Grandma Returns

Sundar brought the old leather pouch home and left it in his cupboard. He did not tell Nakphodi anything because of her delicate mental health. Though he and Nakphodi were married for twenty-one years; and lived in great marital harmony of love and care, yet they slept on separate beds. Obviously, they had no children.

When he came out of the shower feeling fresh, he was surprised to find Nakphodi already wrapped in grandma’s bright red bridal sari. Nakphodi looked very pretty, and was all smiles. She took him in her arms and whispered, “Thank you Sundar, for the thoughtful gift, this I recognize as our grandma’s lost and found sari. Love me, and make me a mother this very moment, dear, and hurry.”

During her next appointment, Nakphodi was declared by her shrink as fully cured of her mental trauma. Her medicine was stopped. She was allowed to be a mother. After a year, she gave birth to a beautiful baby girl and to her and Sundar’s surprise, their baby bore an identical little hole in her nose like grandma. They felt their grandma had returned. Their lovely eighth wonder was named Soudamini. (End)

Prabhanjan K. Mishra is an award-winning Indian poet from India, besides being a story writer, translator, editor, and critic; a former president of Poetry Circle, Bombay (Mumbai), an association of Indo-English poets. He edited POIESIS, the literary magazine of this poets’ association for eight years. His poems have been widely published, his own works and translation from the works of other poets. He has published three books of his poems and his poems have appeared in twenty anthologies in India and abroad.

When I was posted in Mumbai, I had to travel extensively by local trains. Although the service was fast and efficient, there was a downside. The network had spawned pickpockets like locusts on the trains and on the platforms. There was not even a single passenger who could claim to have escaped unscathed from their vicious clutches. Even after years of commuting on the local trains, I could never be sure when a descendant of the Artful Dodger—or the ‘artiste’ himself—would descend on me. In fact, every newcomer who took out an annual pass would be ‘baptised’ by the crowd on sacrificing his purse or pouch. The event would be celebrated by distributing ‘vada pau’ all around!

Once my father came to Mumbai on a visit. In the course of our conversation, the discussion veered round to these notorious bag-snatchers. I cautioned him to be on his guard. No one had escaped intact from their wily fingers, I warned him.

My father guffawed. “You mean you let a trifling pickpocket hoodwink you? What a shame!” A seasoned professor, he had confronted many notorious elements in his life. To him, pickpockets were just another unruly breed that needed to be ‘broken-in’.

Next day we walked down to the train depot to catch the Borivli Fast. My father fumbled his way in the crowd, but managed to get on the train. He marvelled at the way people packed themselves in the compartment like sardines. The stench emanating from the bogey was no less ‘fishy’!

When we reached our destination, once again the crowd swelled and swept us out on to the platform. We got up and dusted ourselves. When I enquired from my father how he had fared, his response was a hearty laugh. “Hats off to your pickpocket friends,” he said and turned his pockets inside out. They were empty. “I had put a one-rupee note in one pocket to entice the thief,” he said. “I don’t know when and how it was swiped from me without my knowledge! Thank God, the thief had spared my other pocket, which contained my currency notes.”

I had to admire his vision. “I think, father, you are much too clever a guy for the pickpockets. Knowing how they target your pockets, you didn’t put all your eggs—I mean cash—in one basket. Good thinking. But how did you decide which pocket to pack the money in?”

He smiled and quipped, “Elementary, my dear smart son!”

Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream…

Our house was situated right on the banks of a canal. For ages it had served the surrounding villages as a lifeline to the hinterland. It remained busy throughout the day—and at night as well—with country boats carrying their cargo up and down the waterway. After the paddy was harvested, it was hulled and then loaded onto large barges by an army of labourers. They carried the sacks to the boat and covered them against the elements with mountains of straw. The entire boat turned into a mobile godown with grains stored right up to the roof.

For the boatman the boat was his home. It was not exactly 3-BHK accommodation, but the men had the ‘basics’ of a kitchen, bedroom and rest area. What about a restroom? Why, the entire expanse of the canal was open to them to answer nature’s call! Taking a bath was no problem. They had a vast ‘outdoor’ swimming pool to jump and play.

When I was a young lad, I used to humour the ferrymen as they cooked their frugal mid-day meal of rice, dal, lentils and a couple of vegetables. They waved their bamboo pole at me. “Do you want to go to Rangoon?” one of them asked.

“Is it very far?” I expressed my curiosity.

“No,” he replied. “I will take you there on my magic carpet and bring you back in a jiffy!” He laughed and told me stories of his travels, till it was time for them to depart. “I will take you with me next time!” He promised. But Burma has been lost to Myanmar and still his promise remains to be fulfilled.

An old stone bridge stands as a sentinel over the old canal. It had a very narrow parapet on which the street urchins stretched themselves and told each other stories. They were no trapeze artistes, but I had to admire their feat of lying prostrate on that narrow shelf. Night after night they slept on it without falling into the water. That too without the instructions of a Yoga guru!

The law of averages has a way of catching up with a vengeance. I came across a news report recently that a street urchin sleeping on the parapet had suddenly fallen to the water below. His identity was yet to be established.

Ishwar Pati - After completing his M.A. in Economics from Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, standing First Class First with record marks, he moved into a career in the State Bank of India in 1971. For more than 37 years he served the Bank at various places, including at London, before retiring as Dy General Manager in 2008. Although his first story appeared in Imprint in 1976, his literary contribution has mainly been to newspapers like The Times of India, The Statesman and The New Indian Express as ‘middles’ since 2001. He says he gets a glow of satisfaction when his articles make the readers smile or move them to tears.

THE GYPSY GIRL

Krupasagar sahoo

34 UP Bilaspur-Indore fast passenger train was about to leave Bilaspur station when two people boarded the 1st class compartment; a young Divisional Safety Officer (DSO) from the platform side and a gypsy girl from the offside.

‘Niklo… Niklo…get out … get out’ screamed the coach conductor and coach attendant, both rushing towards the young girl.

The sudden noise in the corridor was enough for the Safety Officer to come out of the 1st class compartment. He saw a gypsy girl holding a cloth bundle close to her bosom and leaning against the bathroom door trembling in fear. The conductor in black coat and the coach attendant in khaki uniform were vigorously gesticulating and shouting at the girl to get down from the compartment. But by then the train had picked up speed.

The DSO noticed the young dark-complexioned girl wearing choli ghaghara with a black coloured veil on her head. In her arms were silver bangles. Her well-shaped eyes were a striking feature on her face.

‘What happened?’

‘Sir this gypsy girl has got into this 1st class compartment.’

‘Must be by mistake. Why are you being harsh on her? Haven’t you read the rule book of railways? Have you forgotten how to treat women and girls found alone?

He was in a mood to start a lecture on how Indian culture respects women, but the conductor intervened saying, ‘Sir she is a without-ticket passenger. When the squad comes they will catch me only’

DSO looked at the girl; terror was written large on her beautiful eyes.

‘Write in your chart as my attendant. OK?’

‘Ok Sir but shall I make her sit in the 2nd class portion?’

‘Ok’

‘Hey girl! Go that side’ the conductor’s voice was stern.

The girl was still trembling in fear. Her eyes were looking more and more terrorized.

DSO intervened, ‘I see for some reason she is extremely frightened. Let her remain here’

He came back to the compartment and the girl followed him.

Conductor and coach attendant looked meaningfully towards each other.

The girl stood in front of the DSO.

‘Go and sit there’ He pointed towards the opposite seat’

The girl squatted on the floor. The DSO realized that she would have never got an opportunity to sit on a chair or sofa, hence her diffidence.

‘Where will you go?’ She remained silent.

‘Ok…Where is your home?’

She looked confused. DSO understood his mistake. How will the nomads have a house? They keep moving from place to place.

His mind pictured the gypsy camps that he had seen coming up at the outskirts of Bilaspur station. Under the open sky inside the make-shift tents the daily life of the nomads used to go on. Sometimes they were seen squatting on the roadside, selling their wares which included lizard-skins, pangolin-bones, bear-nails, varied herbs and roots, medicines for snake-bites, scorpion-bites etc. Lucky charms, amulets and talisman for ghosts were found among their wares as well. It was also rumored that they were adept at burglary and their girls enticed young boys. He was one never to give in to such rumours. Rather they appeared simple folk to him.

One from that group has strayed into the compartment he assumed.

‘Where are you father and mother?’The girl started sobbing loudly.

‘My mother has died’

‘What about your father?’

‘Father has sold me to an old man. That old man…’

‘What happened tell me?’

‘He was forcing him on me…I bit him and ran away and got into this railway dabba’

‘Where will you go now?’

‘I don’t know’

DSO was in a fix. Should he take him to the police station? But the atrocities meted out by the law-keepers were not unknown to him. Better to rehabilitate him in the railways, he thought.

‘Have you gone to school?’

In Railways even for a class IV job, 8th pass is mandatory. Then the issue of birth certificate - the girl would have never had one - on her. Without these basics it is impossible to get even a menial job in the railways. She can be kept as a domestic maid.

‘Will you stay in our house?’

By now the girl had sensed the kindness of the officer; her terror stricken eyes were now looking calmer and happier.

‘Do you know cooking?’The girl was speechless.

‘Can you make rotis?’

‘Yes’

‘Dal, sabji?’

The girl was a bit confused. DFO knew that these people eat their rotis with onion and chillies. To expect them to cook dal sabji would be a bit too much.

In the mean time the train halted at Kargi Road station and there was a knock on the compartment door. Conductor and attendant had come with tea in two kulhads.

‘Sir! Tea and biscuit’

‘Will you take tea? DSO asked the girl.

She shook her head. She would have never tasted tea he realized. It is a middle class luxury. DSO handed over the biscuit packet to her. The conductor and attendant left the compartment closing the door behind.

The girl started munching the biscuits turning her back. The DSO took out a book from his attaché and started reading.

At Pendra-Road station, again there was a knock at the compartment door.

‘Sir the khoya Jalebis are too good here…For you Sir… ‘Along with conductor, had come the station-master, tea-stall-owner and firewood-merchant. All greeted him. The jalebis in leaf bowls were handed over to him.

‘How much?’ asked the DFO

‘Sir don’t embarrass us’. The tea-stall owner was smiling politely. Others were observing the gypsy girl from head to foot. She put the jalebi in her bag.

DSO was wondering why suddenly these officers were showing such courtesy to him. There was no scope in his post to the ‘so-called help’ to any business-man or supplier. His post was considered a dry-post for which he was at times looked upon sympathetically by some of his colleagues. So getting this unexpected hospitality was a bit surprising.

So is this gypsy girl an object of attraction?

The next stop was Anuppur. It had a fifteen minutes halt. The employees took their meals in the station refreshment room.

‘Sir shall I order for your lunch?’ Conductor asked.

‘Ok order for two.’ The lunch box from home with roti sabji was in his attaché, but he preferred the railway meals.

Two lunch trays were delivered. Again the girl devoured the lunch turning his back to him, as if she had never eaten since many days…

After lunch he lied down on the coach, while the girl kept her cloth-bundle under her head and went to sleep.

At times trinkets on her feet and bangles in her hand made some noise. There was no one in the first class compartment except the two. One or two people passed by, but they must have been railway employees thought the DSO as other than railway officers, few outsiders hardly reserved this bogie due to its high tariff. A fleeting thought passed his mind. Is anyone trying to insinuate him for taking this girl along? But he brushed it aside as he thought what he was doing was according to his conscience.

His destination; Shahdol station arrived. He was given a rousing welcome by the staff. Some days back two trains in this station had had an averted collision. Two trains had come face to face but had just stopped short of a collision at the nick of time. As Safety Officer he had come to Shahdol station to conduct an enquiry of the averted collision.

At the station, he was expecting only Station-Manager and Divisional-Traffic-Inspector, but with them had come Permanent-Way-Inspector, Loco-Inspector, Signal-Inspector and his staff members. They were all greeting him but their eyes were on the gypsy girl.

He sent the girl along with a peon to the guest house and started working on his enquiry.

While working, a call came from his Divisional Railway Manager.

‘Where are you?’

‘Sir at Shahdol’

‘What’s happening there?’

‘Sir! Enquiry is going on...That averted collision case’

‘Ok…OK..Carry on’

He was scheduled for a night halt at Shahdol station. In the night a phone call came to the guesthouse. Operator said, ‘Sir! Madam’s phone’

‘Where are you?’

‘In the guest house’

‘What is happening there?’

‘You know I have come for an enquiry’

‘What am I hearing?’

‘What are you hearing tell me?’

‘Don’t conceal. Tell me openly’

‘Why should I conceal? You tell me what you are hearing’

‘You are with a gypsy girl?’

‘Yes, she is there’ A few second of silence followed. Then from his side

‘Who told you all this?’

‘Why are you travelling with her?’Then a muffled sob sound came from the other side. Before he could say don’t misunderstand, the phone was banged down from the other side.

To placate his wife he tried to connect again, but the operator said, ‘No reply Sir!’

In the night he felt restless, realizing that he is under terrible suspicion. Sound-bites travel faster than light; the truth dawned on him. From Bilaspur to Kargi Road to Anuppur to Shahdol the news has travelled the entire Bilaspur-Anuppur-Katni circle. But his tour programme was approved by the DRM himself! Then have some jealous colleagues spread this piece of juicy news against him? But are all men after the allure of females? Must all females be under the male gaze? Don’t females have an identity of their own?

Should he then abandon the gypsy girl at Shahdol and return to Bilaspur? Let her eke out her own fate. Next moment he thought it won’t be the right thing. There are predators everywhere. The helpless girl will not remain secure. Rather he will take her home and reason with his wife that the gypsy girl will be a good domestic help. He would tell his wife, ‘Your hands are always full with cooking, cleaning and taking care of our infant son. You don’t get regular domestic help. This girl can be groomed for cooking and baby-sitting. Chotu, their son would find a play mate too’ He thought, this would be a surprise gift to his wife.

He decided to cut short his Enquiry and catch the next train back to his headquarters. He can always come back for wrapping up the Enquiry.

The next day he caught the Utkal Express to Bilaspur. At the exit gate there was a huge crowd. So he came out through the Parcel Gate with the gypsy girl in tow.

On the way to his bungalow he thought Chotu will rush out hearing the sound of the horse-carriage and start clapping looking at the horses.

At the gate, the bungalow-peon informed, ‘Madam left for the station with Chotu to go to her maike (mother’s place).

(Translated by Malabika Patel)

Krupasagar Sahoo, Sahitya Akademi award winner for his book ‘Shesh Sharat’ a touching tale about the deteriorating condition of the Chilka Lake with its migratory birds, is a well recognized name in the realm of Odiya fiction and poetry. The rich experiences gathered from his long years of service in the Indian Railways as a senior Officer reflect in most of his stories. A keen observer of human behavior, this prolific author liberally laces his stories with humor, humaneness, intrigue and sensitivity. ‘Didi from Dum Dum’ is one of many such stories that tug the heart strings with his simple storytelling.

OF ALL THE LOVE IN THE PORTRAITS

A rainy Sunday morning of July. The rain that has been pouring incessantly and heavily since last night had frittered out to a slow drizzle. Lounging in the swinging chair in the porch I watched the house boy assisted by another two young men hurrying up and down the flight of stairs at the right corner shifting out the bed and other furniture down to the big hall downstairs from the room at the extreme end of the corridor upstairs and which grandfather used as his bed room for many years. Mother stood supervising the cleaning work and instructing the boys.

A year back on this day grandfather had succumbed to the deadly covid. The rituals of his death anniversary were to be performed today. The priests would arrive soon. My uncles and aunts had arrived since yesterday. The house was all set and prepared for paying homage to the departed soul. The large room upstairs which grandfather had occupied since he came to live with us after the demise of my grandmother had been under lock and key for a long year. Mother and the houseboy made short, infrequent visits to the room to get the room swept and the furniture dusted. I had not stepped into the room for even once. I don’t know why but every time I climbed up the stairs to go to the other rooms one of which served as a guest-cum-study room with book cases lined up against its walls and had to step past the locked room that once was grandfather’s I feel a creepy heaviness on my chest, as if a hard, tight band was pressed across it.

I had always been grandfather’s pet, not my elder brother who now lives abroad. Grandpa could know my mind even before I could think of speaking it out. I could not accurately recollect those days when I visited his house at his workplace along with my parents when he was still in service and lived with grandma. I was maybe four or five at that time but I knew for sure even at that age if I was asked whether I would like to stay back with them when the time of returning arrived, my answer would have been an unhesitant and bold ‘yes’.

They went to live in their native village after his retirement and for the next few years were preoccupied with settling the division of lands and properties among his brothers. Later he got the busy in the renovation work of the portion of the house that came under his share. Grandfather was a man of a friendly and convivial nature who loved to spend his leisure times with both the young and elderly in engagements conveniently suited to both the age groups. I do not know exactly at what particular phase during his stay in his native village, but it may be while grandpa felt that he had discharged his filial and material responsibilities, he made a turn to look back at one of his long-nurtured childhood hobby of painting, a passion that had been since a long time lying dormant under the load of his heavily-demanding official and familial engagements. He got the art-sheets, paints and paint brushes and other requirements collected through one of his nephews from the town. He set out indulgently to painting the landscapes and animals, flowers and faces. May be grandpa wasn’t an artist with rare expertise but his paintings were good, especially the faces he portrayed, whether if the gods and goddesses, humans or animals, looked strangely alive, vivid, and pulsating with life. I had not discontinued the practice of visiting my grandparents in vacations and always looked forward to the days of exhilaration amidst my cotemporaneous cousins, it was a pleasure savoured in anticipation. While I lived with them grandpa used to paint my portraits.

Grandpa did not ask the person he portrayed to sit in his front for long hours while he painted like the professionals do. He would instead, take a snap of the person with his trusted good old Nikon camera and use the photo for the purpose.

I liked to watch him engrossed so assiduously in his work. I found it tough to keep clung to my patience till the unravelling moment. Grandpa will never let me take a look at the unfinished image despite my urgings and ask me calmly to hold on for a day or two. I found several portraits of grandma in different ages, mostly when she was young and was in a bride’s attire. My grandma was a woman of arresting beauty, though not very fair in complexion she owned classic features, a sharp, aquiline nose, big, speaking eyes, thick, long and arched eyebrows and a slightly wide full mouth. Even at that age grandma looked graceful and elegant, wearing a small smile on her face that enhanced the engaging amicability in her personality.

Grandma suffered from some serious ailment and quit the mortal world about a decade or so after grandpa retired from service. Her departure from his life had brought in a great change in grandpa. He seemed to have retreated into a cocoon of silence. A man who loved people around him involvedly, who spent most of his time outdoors amidst friends and relatives had all of a sudden been metamorphosed into a shrunken, resigned and pathetic recluse. He had totally withdrawn himself from painting and the pictures he had portrayed so passionately lay scattered in his room like the abandoned memories of some non-existent time, like the orphaned leaves of storm-blown trees floating aimlessly in the wet air before taking a dive down.

Despite grandfather’s vehement protests, father did not let him continue staying in the village and brought him here, to our home. I was delighted at first at the prospect of having grandfather living with us under the same roof, but the creases of suffering settled stubbornly on his otherwise jovial face disappointed me. The changes that had come over him after grandma’s death were well-pronounced and obvious. He avoided human company, came down only to eat ate a simple, frugal meal only a couple of times a day and went back to the solitude of his room. His seclusion was interrupted only by my occasional invasion to his room on holidays and those evenings when I was not attending the coaching classes. I could still take all liberty with him and it was only I who could make him talk. In those hours of loneliness and dejection he preoccupied himself with books and newspapers. Father had noticed that and got him suspense thrillers from time to time (grandpa was an avid reader of suspense thrillers and father knew of his choice), hoping to God that the engagement would keep grandma away from his mind at least for a few hours in a day. But, perhaps, destiny had another interesting engagement planned for him. And soon.

**

In the form of Roxy, the labrador.

I wouldn’t recount the details of Roxy’s entry into the threshold of grandpa’s reclusion. But just this much that a friend of my father, had bought the twins while visiting Bangalore on an official tour. He had chosen one for himself and inquired if father would care to buy the other to which father had readily consented presumably with a hope that grandfather who harboured a genuine love for animals and birds would find in Roxy, a filler for the blank caused by grandma’s absence.

His presumptions proved true. Grandpa seemed to have taken an instant liking at the creature.

I even noticed a tiny sparkle in his eyes that looked dull and glazed. He caressed the tiny head of Roxy and for the first time in many months I could trace out a semblance of a benevolent smile on his face that smoothened out the hard lines of pain.

Just in a few days he got so fascinated with Roxy that it became a part of his routine to take the dog out to a walk, to feed and bathe it. Roxy could, in a short time succeeded in moving grandpa out of the dark, nightmarish tesseract of grief where he had kept himself confined for so long. Father breathed a sigh of relief watching normalcy returning to grandpa’s life, slowly though.

I and Rocky had the maximum shares of grandpa’s waking hours.

Days slipped into weeks and weeks into months.

Rocky was growing fast. I, too was doing my graduation in engineering after completing the higher secondary course. Though my college was in the same town, I had to shift to the college hostel for facilitating the attending of extra classes and better interaction with the teachers. I came home on Sundays and holidays and grandpa was very happy to see me. I spent most of my time with grandpa and Roxy during those short visits. It was in one of such brief visits I had suggested grandpa to resume painting. He did not show any interest at first and tried to brush the topic aside, but I was not to give up and after long and constant pleadings and persuasions he, just to satisfy me( he said that but I knew he had changed his mind and now trying to relocate his lost interest I painting) picked up the paintbrush. He was keen on acrylic painting and I brought him the easel, art sheets, and colours and brushes.

‘I have lost practice, son,’ he would often say but I urged him on and he did not have the heart to refuse me.

***

‘Come to take a look at it’, grandpa called one day, leaning out from the balustrade, while I was leafing through a textbook lounging in the chair-swing, a mug of coffee in the other hand (my favorite place to sit on). it was a cool, sunny day of late autumn and I loved the luxury of sipping hot coffee soaked in the soft warmth of a benevolent sun.

I went up the flight of stairs, curious to know what grandpa is so excited about. I followed him to his room. He turned to look at me, his eyes twinkling mysteriously and then lifted the cloth draping off the easel. I looked and then stared at the painting. I knew grandpa was a skilled painter but what was in my front was something of which I found difficult to believe was a creation of grandpa! It was an altogether different piece of art, out of his usual line of work, something that revealed a surprising expertise, almost the work of a professional.

It was a painting of Roxy, who was now grown up to be a full-sized dog, sitting on the floor, looking straight forward, presumably at grandpa, with its large liquid eyes. It sat in an upright position, with tucked-in feet, in the full glow of the sun light that invaded the room through the steel- railings of the big window. The background was opaque, not receiving the sunlight, and the image of the dog capturing the full impact of the light on its off-white body looked as if it was embossed on a some kind of a metal sheet of gray and black, creating a brilliant chiaroscuro effect. Its eyes looked alive, as if it was communing something to the one in its front, a pleasant, indulgent glow on a contour exposed to the light. My unblinking eyes remained fastened to the painting for a longtime, wonderment and joy sweeping over me in turns.

‘Liked it?” Grandpa asked after a while, his eyes fixed on the changing shades of amazement my face. ‘Liked it?’ I blurted out without thinking. ‘It is an incredible piece of art. I had no idea you were so brilliant, grandpa.’ I ran back and hugged him tightly. ‘We will put it to display in some art gallery,’ I said, excitedly.

‘I did not paint it with any such intention. It just came out automatically, I do not know how exactly.’ Grandpa refused in his cool and calm voice. ‘I would like to paint one of you and Roxy if you have no objection,’ he added a little dubiously. ‘I would love to be your subject, grandpa. There is no need for you to ask me. Grandpa was tall man, almost six and he bent forward to kiss my forehead. ‘God bless you child,’ he exclaimed fondly. ‘I will take a short break before I start. When you come home in the winter vacation.

Grandpa’s growing years had never been a handicap when it came to his interest and involvement in painting. He was a natural and was in no need of a professional training. Even at that age he was capable of giving complex to quite some professional and younger painters. But he was not in favour of self-advertisement and loved to paint in seclusion, away from the eyes of the world. Sometimes, while he painted I used to watch him intently, wondering secretly if his hand would shake or he might lose focus while he worked at the easel, but nothing of that sort happened ever.

**

I stepped cautiously past grandpa’s room and entered the study, my heart heavy with sorrow. I knew it was not just sorrow, but something much greater than it, and I flinched away from facing it. I was feeling breathless and there was a slight tremble in my legs. I lowered myself to a straight-backed chair by a writing table to regain my calm. I waited for a brief while and then came out and went into grandpa’s room. The houseboy and his helpers had completed the shifting pf the things downstairs and were now washing the room. The easel and some paintings which grandpa had not kept locked in the built in in the wood-paneled wall-shelves, were outside in the corridor perhaps waiting to be carried down.

‘Why haven’t you taken these down?’ I asked Mohan, the houseboy. ‘Ma wants them to be kept at the extreme-end wall of the corridor and to be brought back to the room after the puja is over,’ he said and went back to the job of washing the floor. The easel held no art sheet. I fingered through the paintings and took out one by one to have a closer look. The painting of Roxy was there, sitting in a pool of bright sunlight, against a dark and gray backdrop, looking at grandpa in fond eyes, muted words of love trailing out of its unwavering gaze. I took out another, the one that peeped out from behind Roxy’s, the one that had I and Roxy , both, I sitting on a chair and Roxy sprawled cozily by my leg. It was painted perhaps in last summer. Grandpa had that extraordinary knack to capture the genuine expression in the face, be it an animal or a human and recreate it with an incredible exactness. Roxy did not have to sit for hours together in front of grandpa while he portrayed it, nor did I. It was amazing how he could portray a face so accurately. May be the image that his eyes caught remained etched indelibly in his mind to be reproduced later in his tranquil hours, like Wordsworth’s daffodils.

Roxy was an amazing dog and had a unique way of looking at your face as if it was trying to read the mind of the person it was looking at, a boring and speculative gaze, intense to the extent of bringing in a strange discomfort. In the portrait where I and Roxy were both, it seemed to be looking at my face, I don’t know why, while in all probability it should have been looking at grandpa. I wonder if that was how grandpa’s mind and not his camera had captured it and stored the picture in some secret recess of his mind to be re-lived on the drawing sheet.

There were a few others too, but my attention was caught by these two, grandpa’s favourite ones and mine too. I hadn’t set my eyes on them since Covid snatched grandpa away from us, and from Roxy.

The corridor wore a deserted look, sad and gray. A curious melancholy hung in the air. I could see Roxy scampering and scuttling along the corridor, coming in and out of grandpa’s room, and climbing up and down the stairs. I rubbed my eyes hard and Roxy was gone. Just as grandpa had gone!

Tell Ma I have taken a couple of paintings down to my room,’ I said to the houseboy and picking up the portrait of Roxy and the other one that had both Roxy and me, I came down the stairs.

**

The sound of an impatient scampering at the door brought Amrit abruptly awake. He rubbed his eyes and peered at the mobile screen. It was half past eleven in the night. Why is Roxy scratching at the door at this time of the night? It was not unusual for Roxy, however, to scratch at the door of his room to call me, to draw Amrit’s eyes to something it wanted him to see.

‘What is it Roxy? Why do you disturb me at this time?’ Amrit grumbled. Switching off the air conditioner he got down the bed to open the door. The slumbering house was wrapped in a dark silence. He pulled back the door panels to let Roxy in. A waft warm and moist breeze of late June assailed his face before invading its way into the room. Roxy was not there. He stood silently for a long moment, trying to recollect what made him open the door. The rituals of his grandfather’s death anniversary were performed the day before. And his uncles and other relatives too had left for their respective places. There was a spooky throb in the air that made the hair on the nape of his neck bristle. He looked into the darkness that was slightly relieved by a thin streak of light from the distant light post across the street.

It came to him like a sudden flash of light. Roxy no longer lived with them. They did not know where he was. What was the scratching, scrubbing sound, then? The wind? Some nocturnal bird? Sweat beads on Amrit’s forehead, gathering up together had changed into thin rivulets that trailed along my neck down to his shoulders and chest. Suddenly the wind felt very hot.

He shut back the door and drank some water from the bottle. Then switched on the air conditioner and the light.

Rocky looked at me from the painting; there was an indecipherable and queer look of in its gaze. Was it unhappy? Cross with Amrit because he had let it down? Because he had been responsible to a certain degree for orphaning him? For being a part in destiny’s plan to snatch the man it loved more than its own life, from him? For exiling it to the anonymous streets it was frightened of paving?

Then Amrit heard a small sound, barely above the rustle of a breeze. He let his startled gaze rove around the room. Everything in the room was at its place, untouched, undisturbed; the bed looked cozy and welcoming and the soft hum of the air conditioner sounded soothing. He switched off the light overhead, turned on the bedside lamp, got into the bed and lay down, looking at the portrait of Roxy that stood facing him on the table. It looked even more alive in the silent and dimly lit room. He turned his gaze towards the door and again looked back at the portrait. Roxy seemed to have shrunken slightly in size and somehow diaphanous as if it was slowly dissolving away.

He stared at the big, black eyes of the dog.. at the shade of accusation and grief blended together that lurked there. Startling him the sound of something like a small creature scampering outside the door and scratching at its panels filled the room. This time it was louder and was accompanied by a soft and moaning, as if of some animal that was in pain. The noise grew louder and louder and Amrit pressed his hands to his ears to stop it. But it seemed to have found its way down to his head that was now hammering wildly.

The lights went out.

Rattled out of his wits Amrit groped for his mobile phone and turned on its torch. He was shaking badly and reached forward at the painting of Roxy on the table. The space where Roxy sat, was now blank, a brilliantly lit emptiness against a backdrop of gray and black. Before his fingers touched it the portrait fell down, with a thudding sound. The lights came back synchronizing with the thud. And Amrit sat up on the bed, trembling all over, his breath coming out in erratic gasps.

Both the paintings stood on the table by the window in the similar position as he had put them in the morning. The soft whirr of the air conditioner sounded pleasant and comforting. His throat was parching and he drank more than half a bottle of water in a few swallows.

Roxy, in its real size, eyed him from the portrait, its face benevolent, a speculative look in its innocent, black eyes as if it was trying to make a guess at my mood.

**

The scratching and scraping at the bedroom door brought me awake with a startling suddenness. I sprang off the bed and flung open the door. Roxy was there, wagging frantically its tail and whimpering like crazy. ‘What happened Roxy? Why are you here now, at this time? Are you hungry?’ Roxy scrambled up the stairs still moaning and whining. ‘May be, it is hungry or has hurt itself,’ I guessed as I stood undecided at the foot of the stairs. After climbing up a few stairs Roxy stopped and turned to look back. Finding me still standing at the foot of the staircase it hopped down, pulled hard at my trousers. There was an urgent pleading in its behaviour I found difficult to ignore and followed it up the staircase.

Grandpa lay on the floor, panting for breath, his frail body looking stiff and shrunken.

‘Come down Amrit, immediately,’ Ma called from the hall downstairs. ‘Your father has called the hospital. They are sending the ambulance.’

‘But Ma!’ I called back, ‘Grandpa has fallen off the bed and he is breathless,’

‘You come down first, you silly boy. How could you come near a covid patient without wearing a mask and a face shield?’

I cast a brief look and ran down the stairs to get his mask.

The world was passing through a horrible, once-in-a-century kind of crisis, mercilessly ravaged by a dreaded virus that seemed to have invaded it with a vendetta to kill. Covid was on a rampage across India, too, taking the country in its deadly sweep, destroying lives with a calculated brutality. The newspapers and the social media sites were flooding with facts and fictions about the mysterious virous, that made its way up to the abode of humanity from some anathematic abyss of black horror.

The country was under a lockdown and people remained confined within their houses. Offices and educational institutions were shut down. Most of the official work was done from home barring a few that made physical presence indispensable. Amrit’s father worked from home on his laptop. His college too was closed.

‘The ambulance will be here in minutes. ‘ father said. ‘You need not worry. They will carry him to the hospital.’ Ignoring him, I picked up a face mask and rushed up the stairs. Grandfather, emaciated and pale, peered at me intently. His lips moved as if he was trying to say something. His eyes were like slits and his face was puffy and red. I could not make anything out of the incoherent mumblings except making a guess that he wanted some water. Deciding to give him the water first and then lift him up to the bed, I moved towards the table where stood a water jug and glass. Grandfather mumbled something again, and I turned to look. Grandfather lifted a feeble hand and pointed towards something. I let my eyes travel around the room. There was nothing he could be wanting so desperately at the present condition. A portrait of grandmother hung across the door-side wall. ‘The sickness had made him delirious,’ I presumed and turned towards the table.

**

It was really surprising how grandpa, who never went to crowded places nor was in contact with people who could possibly have been infected with the disease, had caught the virus. He was, as such, a man of healthy and robust built, though a bit on the downslide after the departure of grandma from his life. But he had noticeably succeeded in freeing himself from the grip of that terrible sense of loss. He had befriended Sinha uncle, who had retired from the service of an engineer in the south eastern railways some years back and lived with his wife in a house adjacent to ours. Sinha uncle had two sons, both of them comfortably settled abroad. Uncle and aunty lived alone, in the big house part of which was rented out to one of Sinha uncle’s junior colleagues. He and grandpa did the morning walk together, and had their morning tea routinely either at Sinha uncle’s place or ours. They spent most part of their time in playing chess or discussing politics. There was a remote possibility of Sinha uncle contacting the virus since he too never went to the market or other crowded places. His driver, who lived in the out-house with his wife did all the marketing and his wife managed the household chores. So, when grandpa complained of headache and fever and loss of appetite that night while we were having dinner, none of us gave it a serious thought. Next day he developed a fever and a bad cough. Father called one of his friends’ son, a doctor, who advised to keep him in quarantine and start the protocol treatment.

In the two days that followed grandpa never came out to the corridor and spent most part of the day lying in bed. The houseboy wrapping his face tightly in a thick towel carried the disposable tray of breakfast, lunch and dinner upstairs and kept on the table that stood outside the door. The doctor had got the sputum and blood sample collected through a technician from the hospital where he worked, and proving our worst fears true it was confirmed that grandpa had covid.

Grandpa would phone father and let him know if he needed anything. Father spoke to him many times a day to ensure if he was taking food and medicine in time. On the fourth day he did not call father. The breakfast tray had remained untouched, and the lunch tray too. The houseboy said that grandpa did not answer to his callings and all he could hear was only a faint wheezing. Father called grandpa’s number. It was only after three more calls grandpa picked up the phone. ‘Are you feeling okay father? Why didn’t you eat your meals? Should we go to the hospital?’ ‘I am not hungry,’ grandpa said in a voice that was feeble and shaky. Send something to drink. I am very thirsty.’ ‘Yes, father. I am sending a flask of tea and another of orange juice immediately.’

‘All right son,’ grandpa said in a small voice.

‘Are you sure there is no need to go to the hospital? Should I call in the doctor?’

‘I do not think that is required. Do not worry. I will be fine in a day or two,’ grandfather slicked the switch off.

‘Shall I take a look?’ I asked father. ‘He sounded so weak.’

‘The doctor had strictly warned us to keep him in isolation. We shall wait for one more day. If the fever continues, we shall shift him to the hospital,’ father said.

Roxy darted down the stairs. ‘Had it eaten?’ father looked at Ma. ‘It is not eating properly since the day father came down with fever. Dogs are very sensitive about their masters. Roxy is so fond of father! It could sense that something is wrong with him. it did not eat even from Amu’s hands.’

‘Give it a little milk or something. It has gone skinny and emaciated in these few days.’

Roxy looked at me intently. ‘What was it trying to tell me? I wondered if it was accusing me of neglecting grandfather who loved me so much. There was an irrepressible urge inside me to go upstairs and sit by grandpa, speak a few comforting words to help him keep up his moral strength. The little act of love could have induced some hope in him. But I was scared of the virus. I was afraid for myself. I felt ashamed to look in Roxy’s eyes. What was there in the eyes of grandfather’s dog? Hatred? Condemnation?’ The loving animal in Roxy denounced the selfish human in me.

**

‘Amu! Come down,’ There was an urgency in mother’s cry. I came out of the room and looked down.

Mother stood at the bottom step of the staircase. All the lights in the hall and the porch too were on. Amrit could make out the furrows of fear and agitation on her forehead. ‘Please come down. He is suffering from Covid. Let the medical people take care of him. Do not go very close to him, son’ she pleaded pitifully. The frightening quiver in her voice did something to me. It occurred to me suddenly what a great risk I was running by being in the room with a covid patient. The lethal virus could be easily transmitted through even a brief contact and closeness with a person with covid. I turned back and looked at the pathetic figure that lay curled up on the floor by the bed, partially covered by a blanket. Roxy whimpered and roved around the room. It came out and bit the fringe of my trouser pulling me into the room. But I shoved it aside with a kick from my leg, ran down the stairs, and on reaching down rushed into bathroom. I turned on the hot water tap, picked from the wall cabinet a bottle of Dettol that was one-third full and emptied the contents into the water. I cleansed himself thoroughly with the disinfectant and when I felt satisfied that all the virus I might have carried from my grandfather’s room were washed off, I dried himself and came out.

**

Just as I was putting on a clean pair of trousers and a singlet, I heard the blare of the ambulance. The next minute it rolled into the compound and a pair of uniformed attendants emerged carrying a stretcher between them. They ran across the lit up compound towards the porch. Father pointed at the staircase and they climbed up. Roxy, wagging its tail, followed at their heels. I and my parents waited, holding our breath till they brought grandfather down. Grandfather lay on the stretcher, a frail, scanty figure, his hand was still slightly raised as if pointing at something, a glazed look in his eyes those were now slightly open. He turned his eyes to look at me, and his lips curled. In the hard light of the porch it looked like a rueful smile. It was not exactly a smile, an ugly twist of lips that could have been something between a sneer and a sob. I cringed away from the accusing glance in his eyes.

Roxy shambled after them whining loudly, turning back from time to time to cast an imploring glance at us, probably urging us to bring him back. Father heaved out a sigh, pulled Roxy back into the compound and closed the gate. I could discern a wet look in his downcast eyes, a blend of sadness and guilt.

**

‘Come in, Roxy’ Father closed the gate and called as he moved towards the door. Roxy stood still by the gate, looking unblinkingly at the closed gate as if expecting it to open any moment and grandpa would come in.

‘You call Roxy back,’ father looked at me. ‘It won’t listen to any one else.’

‘Come back here, boy’, I called fondly. The dog did not even turn to look. I walked towards the spot where Roxy stood. ‘I stroked its head. Come back dear. Grandpa will come back soon.’ Roxy flinched away from and lumbered towards the clumps of jasmines at one corner of the compound. It crouched by a jasmine bush and began to pant. I followed it to the jasmine bush and knelt by it. It cast a brief glance at me, but the look of obstinate indifference in its eyes made me feel uneasy. The mute accusation in the large liquid eyes combined with which I guessed could be close to something like loathing, gave me the creeps. Instead of trailing behind me wagging its tail as it used to do earlier, Roxy crouched down, tucking its legs under the belly and rested its face on the ground. A soft, growling sound escaped it and its belly rose up and down in quick succession as it panted heavily. It was behaving strangely, at least I had never seen Roxy like this. I wondered what must be going across in its mind. It was obvious that the shifting of grandfather to the hospital had affected it seriously. I waited for a minute or two, and then touched its head once again. ‘Come on Roxy, have some milk. You are going without food for the last two days. come on boy,’ I coaxed and turned to walk back to the house. Roxy did not budge. It closed its eyes and continued with its panting.

‘Keep a bowl of milk near it. Do not disturb it anymore. It is highly agitated now.’ Mother said.

I placed the bowl of milk by Roxy and patted its head. ‘There is no hurry boy. Finish the milk in your own sweet time,’ I said and left it lying there by the jasmine bush, alone and silently moaning.

I waited for an hour and then moved cautiously towards the gate, hoping Roxy would have finished the milk. The night was fast fading away. The first light of the dawn had sprawled over the compound and on the plants, flowering creepers and the lumps of roses and jasmines. Roxy lay in the same position as I had heft it. the bowl of milk stood by it, untouched.

(hallucination.. present night 2 to 3 am)

Amrit turned on his sides restlessly. It was unusually hot in the room. ‘Who has turned the air conditioner off?’, he asked himself and sat up on the bed, sweat pouring down from him in thin rivulets. He heard the faint rustle of like a sheaf of paper being leafed through and looked around to find out where it came from. He saw his grandfather sitting at the window, painting. The sound came perhaps from the quick and calculated stroke of his brush giving the final touch to whatever he was portraying.

‘What are you painting in the dark, grandpa? He called. ‘And why have you turned off the air- conditioner? Grandpa turned towards him. There was a queer look in his eyes. He did not say a word. ‘What is that you are so busily painting at this time?’ Amrit asked and getting down the bed wandered to where the old man sat. It was the same portrait of Amrit and Roxy, where Roxy was looking intently at Amrit, as if he was trying to read his mind. But now, the Amrit in the portrait looked shrunken and pale, sort of faded, a dispassionate look in his eyes as he touched Roxy’s head. Amrit stood watching, amazed the fading picture in the painting which began to get diminished before his eyes, and grandfather laughed. It was a hard, brittle laughter that made Amrit’s flesh creep. ‘No,’ he cried and his eyes snapped open.