The Bombay Diary - A Doctor's Diagnosis of a Metropolis

After a gap of almost forty years, as a part of my trip to India in 2017, I visited Bombay, where I lived briefly in the 1970s. This is an extract from my diary; my impressions, observations and reflections.

At the outset, I make no apology for stubbornly sticking to the old name, Bombay. For, no matter how laudable the motive may be behind renaming it to Mumbai, the new name just doesn’t roll off the tongue easily! Bombay has retained a special place in my life, as it was my first window to the big wide world when I landed there in 1976 to join the Indian Navy. The culture shock, I experienced on moving from Berhampur (where I studied Medicine) to Bombay was even greater than that I felt on my next leap from India to far away England.

For the following few years, off and on, Bombay became my home, initially the Western Naval Command Officers Mess (The Mess) in Colaba, then one of the Naval ships (where I worked as the ship’s Doctor), and finally the KEM Hospital in Parel, where I worked for my Diploma in Psychological Medicine from Bombay University.

My room was on the seventh floor of the Officers Mess. This area, dubbed loosely as Navy Nagar, lies at the southern tip of Bombay peninsula, jotting out into the Arabian Sea. On the map, it looks like the tip of a fat ball point pen. From my room, I had an aerial view of the prestigious United Services Club, frequented by film stars, next door. The Mess was a grand building, but the most abiding memory of it is the commanding view of the sea from the balcony of my room. From there, I could gaze at the Arabian Sea, spread out to meet the horizon, stretching as far as eyes can see, with the Light House in the distance.

At the time, I just took it for granted but looking back, that was probably the grandest location I ever lived in. After leaving Bombay, I have moved across half the world to England and the USA, living in a variety of residences over last 35 years, but my room in the Bombay Mess had the most majestic vantage point. I always longed for returning to Bombay for a trip down the memory lane but had to wait for almost four decades before I could realise my plan.

I wanted to cover by foot my Bombay again and walk down the roads I used to frequent, and of course visit the Mess, I lived in. But the combined assault from the oppressive heat and the high humidity forced me to retreat into the air-conditioned comfort of the taxis. I still managed to walk part of the distance, gazing at some memorable land marks, still standing. There was Eros Cinema in Churchgate, looking rather desolate, and in a state of disrepair. Here during my very first trip to Bombay, on a College excursion, in 1969, I was refused entry to watch the James Bond movie, “You only live twice, because I looked and was underage!

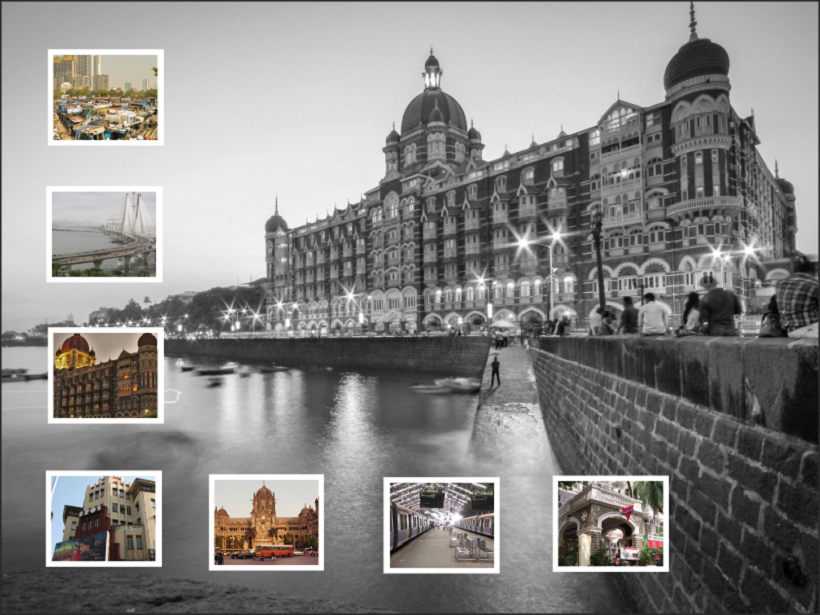

I wanted to revisit the Flora Fountain area, the Victoria Terminus (VT) and Churchgate Stations, Jehangir Art Gallery, Prince of wales Museum and the road from Regal Cinema down Colaba Causeway, all the way to the RC Church. In my first year, this was the only Bombay I knew.

First of all, many of the landmarks, indelibly etched in my mind, were gone. So, the immediate response was one of disorientation. The roads I was looking for were nowhere to be seen and when I thought I had managed to spot them, they were directed the wrong way. After some exploration and with a few helpful tips from the locals, I regained my bearings. Despite lacking in immediacy, somehow everything seemed vaguely familiar. I was puzzled as to what still made the connection with the place. Then it struck me that it was the smell, which had not changed.

I remember the Cuffe Parade, from the olden days with its eye-catching tower of the World Trade Centre (WTC), where development was in full swing in the 1970’s. I used to walk along he road, with the old bungalows on one side and the high-rise structures on the reclaimed land on the other side. During one such walk, I spotted a plaque on the gate of a bungalow, saying Mulk Raj Anand (MRA). Grand though was the gigantic WTC building the image of the renowned writer’s bungalow is still fresh in my memory after so many years. Going by the total transformation of that area, I had little hope of finding any the old relics. I gather the heritage bungalow of MRA was razed to the ground to build a sky scrapper. Amidst all the changes, I found one exception: The garment shop, Charag Din was standing in the same location on Wodehouse road, to my pleasant surprise.

In Regal Cinema, I remember watching the movie, All the Presidents’ Men” and “Enter the Dragon”. I was heartened by the sight of the old shops and restaurants I used to visit during my walks on Colaba causeway. The restaurant, Delhi Durbar, and the sweets shop, Kailash Parbat, were standing although their looks were nowhere like the images, I had carried in my mind.

And, I crossed Cursow Baug, the fortress like building with its impressive gate, whose exterior had changed little. This Parsi colony, which I must have passed by numerous times, still fills my heart with admiration for this community for their care and concern towards their folks and their zeal for maintaining their culture. I gather, this colony covers an impressive area of 84,000 square yards and is home to more than 500 families.

Generally, all the roads felt narrow and crowded. I had vivid memory of wide, tree-lined avenues of the Cantonment area from Afghan Church to the RC Church, with colonial style bungalows spaced comfortably away from the road. This memory was jarred by my findings on this trip; narrow roads, lined up to the edge by concrete compound walls of multi-storied buildings or the buildings themselves, poised to encroach the roads. I suppose, my perspective of space and width had changed over time, but I was left in no doubt about the invasion of the majestic avenues of my cherished Colaba by the monstrous concrete jungle of modern Bombay.

Finally, when I reached the RC Church, I found new Military Check posts stationed on the road to Navy Nagar area. As a casual visitor, I did not expect to be allowed entry into the Mess, but I was at least hoping for a walk around the Mess and see it from the outside. But the guards had little sympathy for my cause. I had no ID on me, let alone any authorisation to enter the restricted area. So, all my pleas fell on deaf ears and permission was refused, denying me a chance to glance at my beloved Mess.

The taxi ride back from Colaba to Andheri was long and seemingly unending, as we crawled through the continuous stream of traffic. From the taxi window, during one of the frequent stops at lights, small notices on road side caught my attention.

“Help wanted. Rs. 9000 for 8 hours and Rs. 18,000 for 14 hours”, along with just a contact mobile number. At first, the money looked good. At the official exchange rate, the offer was better than the minimum hourly wage of £ 7.50. almost the same as the median hourly wage of £ 13.50 in Britain. And, in terns of buying power, the Bombay wage, I thought, might go even further.

So, where is the catch then? Am I missing something obvious?

Perhaps, it is simply the high cost of living in Bombay which would eat into most of the money.

And, what kind of jobs would these be? I wondered. Hope the work would at least be legal. For, there was no hint on the nature of the job, nor any indication of the credentials required. Out of curiosity, I thought of calling the contact number, but other pressing matters soon distracted me.

To ease the tedium, I picked up the Times of India (TOI). The image of the impressive TOI building across the VT station, floated across my mind. Like all newspapers in India, almost half of it was covered in advertisements. I could not help noticing that a sizable chunk of the adverts was for medical investigations, including blood tests and scans. The blood tests were grouped into categories, A, B, C, and so on, starting from Full blood count to Folic acid and the scans covered various organs, including a Full body scan. These were from multiple companies, offering competitive prices, like a panel of blood tests for Rs. 999, and tempting discounts, such as “buy two and get one free”

These were clearly aimed at the growing group of the “worried well” in India, with some disposable income to spare. I shuddered to think how the average Indian can plod through this plethora of tests to decide on the final purchase list. Moreover, I mused on the details of the risk-benefit profile of these tests, offered to the prospective clients, for their informed consent. As to the rigour of their quality control and the regulatory framework for ethical conduct of these farms, it is anybody’s guess. The benefit to the public as a health service may be open to question but they surely represented a bonanza to the firms marketing these tests, I thought.

From a quick mental calculation, I figured, on a conservative estimate, if 1% of India’s 1.2 billion opt for a panel of blood tests and two scans a year, at a rough price of Rs. 3000 for the lot, this coms to a market of 3,600 crores.

But what about the anxiety, caused by the false positives and the array of incidental findings of little clinical significance, arising out of these tests? This remains incalculable.

But far from glossing over this issue, it is perhaps already factored into their business plan. For, this pens up additional streams of revenue through arranging consultations with specialists and super specialists, marketed by the same or their sister companies.

Perhaps, I am a biased observer, as my friends would tell me, as I was overlooking the entrepreneurial spirit of the younger generation. Clearly, this has been on the rise, since I left India in 1980s. With the liberalisation of the Indian markets, goods and services, hitherto unimaginable, are in steady supply to meet the insatiable demands of the rising middle class in India. During my stay in Bombay in the 1970’s I was vaguely aware of the “Dhobi ghats” of Bombay. During this return trip, I realised, a visit to the Dhobi ghats had become a tourist attraction with organised tours to their working/living quarters, ironically, situated next to the Mahalaxmi station. The workers there earn a pitance, by Bombay standards but their money gives a substantial boost to their family income back home. I hope, the income generated from the organised tours is not entirely for the benefit of the Tour companies, marketing them but a portion of this, however small, goes to the workers of the Dhobi ghats.

But medical care, tests or treatments, are clearly not ordinary commodities, I would argue. In marketing these services without due regulatory control, there is an inherent danger of exploitation of the public’s fear of serious diseases, which becomes a convenient bait for such tests to feed the profit motive of greedy entrepreneurs.

No trip to Bombay is complete without a ride on her local trains. The experience of train ride in my initial days there was instrumental in toughening me up, preparing me for the rough and tumble of city life. The crowds on these trains at first sight were terrifying to the timid mind from the small town of Berhampur.

I remember planning my travel from Churchgate to Parel and arriving at Churchgate station to catch the train. The train arrives at the station and gradually comes to a halt. I would be waiting nervously on the platform, gathering courage for the dash to board the train, hoping to get onto the train early on, to grab a seat. But the ferocity of the momentum from the crowd pouring out of the compartments, would sweep me far away from its entrance! Hoping for success on the next attempt, I wait patiently on the platform with the knowledge that local trains run on a frequency of roughly every few minutes. But, alas. the same experience is repeated with the next train. I was totally at a loss, with no luck in getting a seat in the train even from the starting station!

I finally learnt the knack of getting a seat on my train ride from Church Gate to Parel. Somebody suggested; in stead of getting on the train at Churchgate, I get on the train at Marine Lines, the next station within walking distance away from Churchgate. The trick is to get on the train on its journey approaching Churchgate station, as there would be hardly any crowd in Marine Lines as it is the penultimate station for the train.

During this trip, I took the train from Andheri to Churchgate, for the sake of reliving my old memory. The cost of the train ticket was Rs. 20, a sign of the affordability of Bombay’s local trains for the public in this city of billionaires. On the way, we crossed Elphinstone Road station, which had recently witnessed the loss of many lives from a collapse of the overhead bridge due to sheer overcrowding. I could imagine myself walking on that bridge as I had done so many times during my frequent trips to the KEM Hospital.

I silently thanked my stars for safeguarding me from this fate on many such journeys I had made on that bridge and paid my homage to the unfortunate souls who lost their lives on that fateful day. It seems on that day, a sudden heavy downpour prevented people from leaving the station, thus creating a backlog of people disembarking from the trains. And, an innocuous remark from one in the crowd, saying, “phool gira” referring to a flower, which had fallen off, apparently sparked off a stampede, because it was overheard as “pool gira”. The bridge was rickety and was overdue for replacement, which sadly had got delayed.

Of course, some things were new to me. It took me a while to grasp the concept of PayTM and MiFi, which I hadn’t heard of in Britain. For about Rs. 2000, his contraption called, MiFi allows wireless connection to internet by several devises. It was a novel experience for me to use the MiFi and electronically order and pay for taxis and other services. It made me realise how primitive was my knowledge of new technology!

Bombay traffic in my experience was clearly more orderly than that of many other cities in India. In fact, I found it better than what I expected as, I had imagined the worst. All said and done, one thing seemed to be as difficult as ever. As my taxi was nearing my hotel, I saw crowds waiting patiently by the road side to cross. This brought back an old joke, from the 1970’s.

Two friends are overheard, standing on either sides of a busy road in Bombay. One of them is desperately trying to cross to the other side. After a prolonged wait, he was getting increasingly frustrated by the continuous traffic, thwarting his attempt to cross the road. Just before giving up, in sheer exasperation, he shouts out to his friend across the road, “Hey, how did you manage to cross?”. He replies, “Well, I was born on this side!”

I wondered, what had changed in the intervening decades. In this age of technology and virtual reality, perhaps the need to cross the road is less urgent now! Or, may be not. I am not so sure.

Dr Ajaya Upadhyaya

11 February 2019

Dr. Ajaya Upadhyaya is from Hertfordshire, England, a Retired Consultant Psychiatrist from the British National Health Service and Honorary Senior Lecturer in University College, London.

Viewers Comments